On August 4, 1860, the Putnam Grounds in Brooklyn was the site of a baseball game between two of the area’s top teams, the host Putnam club and the Excelsiors. The contest, while having the curiosity factor of being a “fly game” — one in which a ball had to be caught on the fly to register as an out, rather than on one “bound” — would normally have been most notable for being a warm-up for the Excelsiors’ game against the Atlantics five days later, one that could wrap up the national championship.

But this day holds a special place in the history of Jim Creighton, the 19-year-old pitching phenom who had taken the game by storm. It was the day that the Brooklyn Daily Eagle sent a reporter to weigh-in on the legality of Creighton’s pitching delivery.

But this day holds a special place in the history of Jim Creighton, the 19-year-old pitching phenom who had taken the game by storm. It was the day that the Brooklyn Daily Eagle sent a reporter to weigh-in on the legality of Creighton’s pitching delivery.

“We have heard so much of late, in Base Ball circles, about the pitching of Creighton, of the Excelsior Club, and the fatal effect of the scores of those who bat against it,” the correspondent wrote in the Aug. 6 edition of the Eagle, “that we determined to judge of the matter ourselves.”

From the moment of Creighton’s debut as a pitcher a little over a year earlier, his performance had been analyzed and debated. A pitcher was restricted to an underhand delivery, with a stiff wrist, and to date no one had been able to meld a fast delivery with any degree of control. The Eagle correspondent noted that Creighton delivered his pitches “from within a few inches of the ground, and they rose up above the batsman’s hip, and when thus delivered, the result of hitting at the ball is either to miss it or send it high in the air.”

Yet, if Creighton was stretching those rules, no one had been able to conclusively call him on it. “We went prepared to watch his movements pretty closely,” the correspondent wrote, “in order to ascertain whether he did pitch fairly or not, and whether his pitching was a ‘jerk,’ ‘an underhand throw,’ or a ‘fair square pitch,’ and the conclusion we arrived at was, that it was unquestionably the latter.”

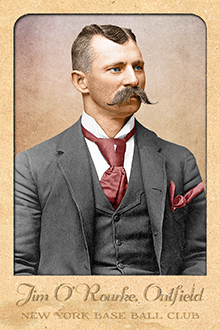

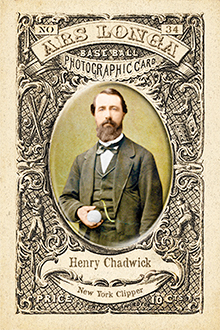

The author of the report is almost universally believed to be Henry Chadwick, the preeminent sports writer of the day and the only scribe to be elected to the main wing of the Hall of Fame. So, the great Chadwick had signed off on Creighton’s pitching . . . the matter is settled, right? Any number of short biographies on Creighton have referenced this article.

The author of the report is almost universally believed to be Henry Chadwick, the preeminent sports writer of the day and the only scribe to be elected to the main wing of the Hall of Fame. So, the great Chadwick had signed off on Creighton’s pitching . . . the matter is settled, right? Any number of short biographies on Creighton have referenced this article.

But there’s a good chance that they’re all missing the point.

First off, if this was indeed Chadwick writing for the Eagle, he intentionally misleads his reader. The piece is written as if this is the author’s first exposure to Creighton in action, but we know that Chadwick attended, at the very least, the Excelsiors’ previous two games, including the epic 23-4 thumping of the Atlantics two weeks earlier.

Chadwick’s intent appears not to have been to give Creighton his seal of approval as much as to admonish the whiners who claimed that the pitcher was stretching the rules to deliver an unhittable ball. “Now that we have seen it attentively,” he wrote of Creighton’s pitching, “our wonder is that such experienced batsmen as the Atlantics could ever be mastered by it in the way they were on the occasion of their contest with the Excelsiors.”

What moved Chadwick to weigh in on the Creighton controversy at that point? It may have been that he judged the Atlantics’ top hitter of being guilty of sour grapes. Years later, he related a conversation from early in that first Excelsior/Atlantic game, when lead-off batter Peter O’Brien returned to the bench after striking out. “Why, we can’t hit that pitching, Henry,” he moaned. “The fact is, it’s underhand throwing.”

Was Chadwick’s subsequent Eagle article intended to advise O’Brien to suck it up and improve his attitude? Perhaps. The piece on the Excelsior/Putnam game concluded with “We observed that P. O’Brien seemed to watch Creighton’s pitching closely, and as he made no objections as to its fairness, we presume that it met with his entire approval, for Peter is not a man to hesitate about doing his duty.”

The game was fairly typical of the Excelsiors’ season. After giving up two runs in the first inning, Creighton shut out the Putnams for the next five frames as his team built a 15-2 lead, on the way to a 23-7 victory. Creighton scored four runs to lead his team at bat.

But a much more important game was in the offing.

Three innings into their rematch with the Atlantics, one could have forgiven the Excelsiors if their thoughts drifted to the fitting of a collective crown. Ahead, 8-0, before an enormous crowd of 15,000 that ringed the Atlantics’ field at the corner of Marcy and Gates avenues, their teenage pitcher again dominating the reigning champions of the game, it appeared inevitable that the title was going to change hands.

Creighton was on the verge of cementing his place in this history of the game, perhaps a place so high that even casual fans would remember his name today. Instead, he was about to hit rock bottom.

The Atlantics’ seventh-inning explosion looms large in the annals of a club that was already renowned for late-inning rallies. Everyone hit Creighton, and hit him hard. Eight of the nine batters in the lineup scored at least one run, and the one who didn’t, John Price, had what might have been the hardest-hit ball in the inning, being robbed of a hit on Edwin Russell‘s catch in left field that was judged one of the finest ever seen. In succession, Archie McMahon hit a two-run double, O’Brien brought him home with a double and then scored himself when Joe Oliver tripled. When it was over, the Atlantics had nine runs and a 15-12 lead.

One wonders what happened to Creighton. In the 21st Century, the turn of events would be constantly dissected through the 24-hour news cycle, theories would be offered, replays would be shown ad nauseum. The reports of the time merely passed it off as a bad day, when the star pitcher didn’t have his best stuff. “Creighton’s pitching was very good for the first few innings,” the New York Times reported, “but it became manifest in the seventh innings that he was not in condition.”

It was true that season that Creighton tended to be stronger in the early-to-middle innings, and either tired or let up a bit in the late going, when the game was usually in hand. But he never in his career was hit as hard as he was that frame. He saw out the inning, but Leggett brought in Russell to pitch the final two innings, and the Atlantics didn’t score again.

The Excelsiors didn’t give up, slicing a run off the lead in the eighth. In the ninth, Asa Brainard led off with a double, but appeared he would be stranded at third when the next two batter went out. Leggett responded with an infield single, with Brainard beating a throw home. But Dickey Pearce, playing catcher, snapped a throw to second baseman John Oliver, catching Leggett trying to take an extra base on the play. The game ended, and the series was tied. The third game would be played two weeks later at a neutral site, the Putnam Grounds on which the Excelsiors had recently won. But which Creighton would show up for the game? The one who had dominated the Atlantics in July, or the one who had been driven from the box in the second game?

The rubber match between the Excelsiors and Atlantics would mark a turning point in baseball history but, unfortunately, not through the heroics of anyone on the playing field. It was the most significant event in a season in which interest in the presumptive “National Game” took a quantum leap, and might best be represented as the dividing line between the sport’s genteel beginnings and a modern era in which the pursuit of victory superseded any previously accepted niceties.

Otherwise, things were quite different. The Putnam Grounds were smaller than the home fields of the Excelsiors and Atlantics, but the crowd (estimated at 15,000) was just as large as the previous two games. The relative lack of women in the crowd was noted, their presence generally being seen as a civilizing factor on the male supporters.

And then there was the gambling factor. Although newspaper reports tended to characterize those who were wagering on baseball games as the lowest form of fandom, there’s no question that the sport’s rise in popularity went hand in hand with the ability to put down a bet on the outcome of a game. When the series had opened, the Atlantics had been made a narrow favorite by oddsmakers. The first-game thumping they experienced likely shifted those odds, but the reigning champions’ thunderous comeback in the second game had not only evened the series, but gave the impression that their mojo had been restored. It was clear from newspaper reports that most of the bettors in attendance of the deciding game were looking for an Atlantic victory.

Despite the Excelsiors’ early lead, the game was tight and tense, with each team looking rattled at times in the field. Errors and passed balls contributed to many of the runs scored over the next few innings, but after the Excelsiors scored a pair in the top of the fourth to take an 8-4 lead, the game took a turn.

With one out, the Atlantics’ Hamilton singled and advanced to third on a stolen base and a passed ball. Joe Oliver took his time with Creighton’s pitching, but on the 22nd offering, he hit a foul tip that hit Leggett in the neck and then fell to the ground. The Excelsior catcher was able to pick up the ball on the bound. The umpire, however, didn’t see the catch and didn’t signal Oliver as being out.

The umpire was Richard Thorn, the pitcher for the Empire Club and something of an interesting choice for a game with such an intense atmosphere. He was considered a swift-ball pitcher in his own right, but an 1857 article in Porter’s Spirit of the Times characterized him as one who “sometimes let his feelings get the better of himself,” becoming agitated with batters who let what he considered perfectly good pitches to go by without swinging the bat.

Oliver, noting that Leggett had made the play, began to head back to the bench, but his teammate, Archie McMahon, directed him back to the plate. This may seem like nothing to the modern fan, but it was considered a breach of good sportsmanship in 1860, to try to benefit from such an error. Leggett explained to Thorn that he had caught the ball on the bound, and Leggett, being a gentleman and all, certainly wouldn’t lie about something like that, so Thorn reversed his call, and Creighton retired Mattie O’Brien on a pop up to second base to end the inning. The Atlantics had missed a chance, and the crowd began to get restless.

The Excelsiors went down in order in the top of the fifth, after which things began to get more heated. Pearce led off by reaching on an error, and Charlie Smith slammed a double to bring him home. McMahon followed with a single to left to cut the margin to two runs. He stole second, and when Peter O’Brien fouled out to Ed Russell at first base, McMahon took third. But he slid past the base and when his hand pulled off it, John Whiting slapped a tag on him and Thorn called the runner out.

Rather than accept the call, McMahon vigorously argued that it didn’t matter that his hand was off the base, because his foot was still in contact. Chadwick, in the Clipper, wondered if that was so, then why did McMahon feel the need to try to get his hand back on the base? Whatever the case, Thorn wasn’t buying it. His call held, and Creighton then induced John Price to pop out to Thomas Reynolds at shortstop to end the inning. But the tension in the park had finally bubbled over.

“The rowdy element which had been excited by a fancied injustice to McMahon,” the New York Times reported, “now became almost insupportable in its violence, and shouts from all parts of the field arose for a new Umpire; the hootings against the Excelsior Club were perfectly disgraceful.”

But it was the Atlantics who appeared to be feeling the pressure in the top of the sixth. With one out, Mattie O’Brien missed Leggett’s pop up back to the pitcher, and then failed to pick up the bound as well. Creighton grounded into a force out, but was safe at first when Price dropped the relay. Charlie Smith then missed Russell’s liner to third base, and when he tried to throw out the Excelsior runner, Price dropped another throw.

All of this was taking place against a rapidly deteriorating background, as elements in the crowd became louder and began straining against the boundaries of the field that police officers present were attempting to maintain. At one point, Leggett threatened to take his team off the field unless the situation improved, but by the time Price had committed his second error of the inning, the scene had gotten worse rather than better, and Leggett decided he’d had enough.

In that moment, Joe Leggett was a man with a a foot in each of two worlds. The Excelsiors, among the teams that competed at the highest level, were perhaps the last representatives of the first era of baseball, when the game was a gentleman’s sport, and sportsmanship trumped all other considerations. On the other hand, winning was clearly important to the Excelsiors captain. He’d drilled and organized his team to be champions, and, as far as Jim Creighton went, he accepted whatever corner-cutting the pitcher had done to become the best at his craft, as well as whatever financial arrangements the club may have come to with the young phenom. But this scene was apparently one which Leggett could not accept.

Peter O’Brien caught up with Leggett as the Excelsiors were leaving the ground and tried to talk him into returning. When that didn’t work, he asked if the Excelsiors would at least agree to call the game a tie, a request to which Leggett acceded. And thus ended, in embarrassing fashion, the most significant game in the sport’s most significant season to that point.

O’Brien and the Atlantics got what they needed: in the heat of the moment, there was no telling whether or not the game would be recorded as a forfeit to the Excelsiors, but a tie ensured no resolution to the series, and therefore the Atlantics kept the championship.

For the gamblers who brought about the end of the game, their ends were also accomplished. No result meant all bets were off, and with the Atlantics appearing to be on the verge of throwing the game away in the field, there’s little doubt that many a wager was saved by the game ending prematurely. The timing of the uproar was likely no mistake, either. This was a very slow-moving game, as batters on both teams were waiting out the opposing pitchers. The report in the Clipper included a very detailed, multi-tabled box score, so we know exactly how many pitches were thrown to each batter. In five and two-thirds innings, Mattie O’Brien had thrown 334 pitches. In five innings, Creighton had thrown 331, including 71 to just two batters, Hamilton and Oliver, in the second inning. The game had started at 3 p.m. and had already run 3:20 when it ended, which means that it likely wouldn’t have gone more than seven innings before being called on account of darkness. And with the Excelsiors on the verge of adding to their lead due to the Atlantics’ misadventures in the field, it was no wonder that people with money on the line began causing a commotion.

Interestingly, modern re-tellings of the game have failed to mention something that the New York Times report thought important enough to include in its lead: “It would not be entirely correct to say that this result was unlooked for, as statements have been openly made within the last few days that the Excelsiors would not be allowed to win in a close contest.” Boxing matches had been known to have been disrupted in this manner, in order to wipe out betting responsibilities. Perhaps baseball was, for the first time, being victimized by that mindset.

The result was left to be rehashed in conversations among baseball fans and in the press. The media initially sided with the Excelsiors, claiming that while the Atlantics themselves may not have been responsible for the crowd’s behavior, they did nothing to try to calm the hoard.

“We certainly think he acted wisely in so doing,” wrote Chadwick in the Clipper, in regard to Leggett leading his team off the field, “and we only regret that he was not supported in his course by the Atlantic nine, as that was the only method of putting a stop to the outrageous conduct of the low gambling set that were present on the occasion.”

“We hope it will be the last great match that takes place,” wrote the correspondent from the Brooklyn Eagle, “if such scenes as took place yesterday are to result from them. Such confusion and disorder, and such gross interferences with a match by the spectators, we never witnessed. If the admirers of this manly pastime desire its future welfare, they should at once proceed to adopt stringent rules among the various clubs, against betting on the result of the matches played, for it was unquestionably a regard for their pockets alone that led the major of those peculiarly interested in the affair, to act in the blackguard manner they did.”

But was the uproar really so bad, so vile, so beyond the pale? What if the modern fan could see film clips of what transpired? Would he or she think it no worse than what you could find in any ballpark in this day and age. Would we be appalled, or would we just smile at what might now be considered an overreaction? We, of course, can’t know; all we have is the written word, and it’s likely that the media would have sided with a more gentlemanly standard for fandom.

At any rate the Atlantics weren’t buying it. The tipping point likely came two days later, when the Excelsiors played the Knickerbockers, running up a 30-0 lead before easing to a 32-9 victory. An Excelsior club official weighed in as to how much more satisfying an experience it was to compete against such a gentlemanly club, rather than . . . well, you know . . .

The Atlantics responded with an official press release that questioned why they could have been expected to bring to order a crowd of many thousands when the large corps of policeman on site couldn’t manage it. The letter, formulated by club members and signed by secretary F.K. Broughton, insinuated that perhaps the problem was with the Excelsiors, that they were too soft to deal with a little spirited rooting, the kind of stuff the Atlantic players would just ignore. “We would recommend to those aspiring to the championship not to be too hasty in leaving the field,” the letter concluded, “as it is a ‘poor road to travel’ and does not lead to that envied and coveted position.”

A short while later, an anonymously-sent package arrived at the Atlantic Club, containing what was claimed to be the game ball. Details of the game were written on its side, including a pointed reference to the fact that the Excelsiors had been leading when the game ended. The Atlantic Club members were not amused, although they did keep the ball for their trophy case.

And so it went. Atlantic supporters wrote to the newspapers suggesting that there wasn’t sufficient threat from the crowd to end the game, echoing the official club stance that the Excelsiors’ sensibilities were a bit too tender. Thorn, the umpire, weighed in with an “official” interpretation that did nothing but confuse both sides. There was initially some hope that the game would be replayed, perhaps without a crowd allowed, but that was never going to happen; there was no good feeling remaining between these two clubs.

At some point, Excelsior Club officials announced they would no longer compete for championships, which essentially meant they would no longer consider scheduling games with the Atlantics. And they never did. Although the players would sometimes meet as teammates in all-star competitions, the two clubs would never again meet on the field.

One of the biggest losers in the whole debacle was Creighton, or rather his legacy. The prevailing attitude after a month or so of hashing out the tie game through the newspapers was that although the Excelsiors were leading, the Atlantics had the momentum. This may or may not have been the case. Surely the Atlantics appeared on the verge of falling apart in the field. And Creighton did manage to record the crucial final outs of the fourth and fifth innings. What if he had been given the chance to see the game to its conclusion, to gain redemption for his failings in the second game? Would his name still be remembered, more than a century and a half later? Would he have been elected to the Hall of Fame?

Certainly no one at the time was worrying about the legacy of a 19-year-old. He’d have plenty of time to add to his list of accomplishments.

What do you do when the high point of your season ends on such a frustrating note . . . and there are still eight games left on the schedule? You press on . . .

A week after defeating the Knickerbockers, the first game in a home-and-home series with the Empire club had Creighton facing off against Thorn, the pitcher who had umpired the third Excelsior-Atlantic game; the Excelsiors won easily, 23-7.

That set the stage for another interesting pitching match-up, when the Excelsiors squared off against Union of Morrisania. The Unions’ Berney Hannegan was another young fireballer, but with nowhere near the control of Creighton. Indeed, part of his effectiveness might have been the result of batters not willing to stand in against some of his wilder pitches. Against the Excelsiors, he was at the top of his game, but Creighton was better, allowing only two runs in the first eight innings of a 7-4 victory.

After a 46-15 victory over Independent of Brooklyn, it was time for the Excelsiors to once again hit the road, and for Leggett to reconnect with an old friend.

Sometime after joining the Excelsiors, Leggett had made the acquaintance of a Baltimore man named George Beam who, like Leggett, was a grocer. When Beam made a business trip to Brooklyn, Leggett invited him to take in an Excelsior game, and Beam was so taken with the sport that on his return home he began organizing his own team which he of course called the Excelsiors. Now the Maryland Excelsiors wanted to host their Brooklyn namesakes.

The final score was Brooklyn Excelsiors 51, Maryland Excelsiors 6, which was not a surprise or even much of a disappointment for a home crowd that had pretty much expected their own team to get thrashed and were apparently happy just to see baseball played at its highest level. Perhaps the Brooklyn team was further inspired to perform for the many Southern belles in attendance; Asa Brainard, Whiting and Reynolds were reportedly so enthralled by the view that Leggett had to remind them to keep their heads in the game.

The game would otherwise be of little significance but for a couple of chapters it added to the Jim Creighton legend.

Beam, apparently wanting to get the first look at the young Excelsior pitcher, installed himself as the Baltimore lead-off batter. One correspondent wrote that Beam “was hardly prepared for the swift, lightning-like balls which Creighton began to favor him with. He struck once without effect and looked astonished; he struck again, and missed, and looked surprised; again he made an ineffectual stroke at the ball, and gave up his bat, apparently in wonder and admiration of the performance of the pitcher.”

Creighton had a 36-2 lead after five and a half innings, when he switched places with Russell in left field. Russell quickly gave up a run and Baltimore had runners on second and third with none out when a fellow named Shriver hit a long drive to the outfield. Creighton ran the ball down, making the catch with his back to the action, then spun around to whip a throw to Whiting at third, who then relayed the ball to Brainard at second, catching both runners before they could return to their bases in what may be the earliest documented triple play. As an added bonus for the crowd, Brainard reflexively tossed the ball to first base, where A.T. Pearsall caught it and comically brandished it in case there were any other candidates for being put out.

On the way home from Baltimore, the Excelsiors defeated a Philadelphia all-star team, 15-4, and a week later recorded another 23-7 victory over Empire. A little over a month later, they ended their season with yet another significant Creighton moment.

On November 5, the Excelsiors met the St. George Cricket Club, which was the most prominent cricket organization of the era. While that might not sound like much of an opponent for one of the ranking baseball clubs of the day, it should be noted that many of the top baseball players of the day also played cricket, Creighton included, and similar batting and field skills were required in the two sports.

According to newspaper reports, the St. George Club looked among its ranks for its best fielders to put in its lineup. It probably would have been better off choosing its best batsmen, as Creighton accomplished something that had never been done before: he pitched a shutout, winning, 25-0. Coverage of the game was scant, so there are no details about the number of baserunners he allowed, but it was a fitting end to a breakout season, one in which Creighton won 17 of 20 games, with two one-run losses and a tie.

Even so, the Atlantics stole the headlines once again; only a week earlier, they had won the rubber game in a three-game series with the Eckfords to defend their national title.

After the experiences and successes of 1860, you would think that a rising talent like Jim Creighton would be pretty much unbeatable. And in one sense you’d be right. In 1861, Creighton didn’t lose a single game. Didn’t win a single game, either.

Students of history will no doubt note that momentous things were happening in the country at the time. One day after Creighton shutout the St. George Club, the American electorate voted in Abraham Lincoln as the nation’s 16th president. But it was a divided America that voted. Lincoln was pretty much a shoe-in, given that the Democratic Party had split, with different candidates in the North and South.

For the next month and a half, the question of secession was debated throughout the South, until South Carolina took the step of leaving the Union on Dec. 20. By early April, six other states had followed suit, and on April 11, the Confederate States demanded the surrender of Fort Sumpter, the fortification in the middle of Charleston Harbor to which Major Robert Anderson had removed U.S. troops a week after South Carolina had voted to secede. After two hours of bombardment by Southern forces, Anderson chose to return fire, giving the honor of ordering the first shots to the fort’s second in command, a union captain named Abner Doubleday. Yes, that Abner Doubleday; firing the North’s first official shot of the Civil War was something he actually did do.

In New York, the newspapers had featured stories only a couple of months earlier about the prospects of another great baseball season, but those predictions came crashing down. The sport didn’t exactly shut down; these were, after all, amateur clubs not playing a set schedule. But after taking two steps forward in 1860, it definitely took one step back. The Atlantics, after playing 12 games the previous year, played only seven in 1861. They split a pair of games with the Mutuals of New York, but never played a rubber game and therefore held on to the title. The Eckfords’ schedule dropped from 17 to 12 games, the Gothams from 13 to three, the Eagles from nine to five, the Unions from 10 to four . . . baseball had certainly not died out, but it seemingly had hit the pause button.

Three significant teams played no games in 1861: the Knickerbockers, the Putnams . . . and the Excelsiors.

Actually, it would be wrong to say that those teams were dormant. They simply confined themselves to intersquad play. Reportedly, more than 90 members of the Excelsior Club signed up to go to war, including John Whiting, the hard-hitting third baseman, and Joe Leggett, the heart and soul of the team. A third starter, fancy-fielding first baseman A.T. Pearsall, was just finishing up medical school during the first year of the war, and soon after disappeared. A native of Alabama, he’d returned home to serve the Confederate Army as a field doctor. When word got back to the Excelsiors about Pearsall’s allegiance, he was drummed out of the club.

It was almost certainly the departure of Leggett and his leadership skills that led to the Excelsiors’ lack of activity. All of those intersquad games had to have been a bit boring, but at least Creighton had the diversion of competing for the American Cricket Club, where he was developing into one of the area’s top bowlers. But as the calendar turned to summer and other clubs began to play match games, perhaps the Excelsiors’ stagnation became too much. So Creighton and Asa Brainard jumped ship, joining the Atlantics.

One would think that such a “revolving” of top players would have been a major story, but the large newspapers didn’t appear to touch on it. Perhaps no one outside the two clubs knew. Whatever the case, the pair had a change of heart and three weeks later returned to the Excelsiors, presumably with their tales between their legs.

The only newspaper report of this coming and going appears to have been in the Brooklyn City News. “We understand from good authority that Messrs. Creighton and Brainard have resigned from the Atlantic club,” the correspondent wrote, “and withdrawn their resignations form the Excelsiors, so that they are still members of the latter club, and will take part in their matches this month.” The “matches” referred to were apparently only intersquad games.

The episode could be viewed as a window into Jim Creighton’s character, but in this case it’s easy to be charitable to the young pitcher; he likely just wanted a chance to play ball. Even the Brooklyn City News story made the point that “No club can expect to retain their members unless they take active part in the matches of the season.” Creighton and Brainard were teammates on the American Cricket Club along with the Atlantics’ Dickey Pearce, with whom Creighton had struck up a friendship. It is, of course, possible, that there were under-the-table payments involved, because with no games being played, whatever financial arrangements the Excelsiors had with Creighton may have been off. In the end, it appears that, given the animosity between the two clubs, the transaction was too much of a powder keg to hold.

But the highlight of the baseball season occurred a month later. Attendance was down all around, and interest was muted, so Frank Queen, the editor of the New York Clipper, decided to do something to jump-start that interest. The first baseball event to truly grab the public’s attention had been the Fashion Course game of 1858, a best-of-three all-star series between the top players in Brooklyn and New York. Queen proposed having the Clipper sponsor the Silver Ball Game, so named for the trophy for which similar select teams from Brooklyn and New York would compete.

But the highlight of the baseball season occurred a month later. Attendance was down all around, and interest was muted, so Frank Queen, the editor of the New York Clipper, decided to do something to jump-start that interest. The first baseball event to truly grab the public’s attention had been the Fashion Course game of 1858, a best-of-three all-star series between the top players in Brooklyn and New York. Queen proposed having the Clipper sponsor the Silver Ball Game, so named for the trophy for which similar select teams from Brooklyn and New York would compete.

The game was a success; the quality of play was judged to be high, and eight thousand spectators, the largest crowd of the year, showed up in Hoboken, N.J., at the Elysian Fields. The Excelsiors, Atlantics and Eckfords each contributed three players to the Brooklyn lineup, with Creighton joined by teammates Pearsall and George Flanly. And Creighton was the man of the hour, dominating the competition as he had the year before in an 18-6 Brooklyn victory. Pearce had the honor of catching Creighton on the afternoon; Joe Leggett was back from the war, but not in playing shape, so he instead stood in as the umpire.

But that wasn’t the final activity of the year for Creighton. On Nov. 7, a benefit baseball game was held for Pearce and Creighton in Hoboken.

“The large circle of friends of Mr. Pierce (sic) conceived of the idea and arranged the match for his benefit,” the Brooklyn Eagle reported, “but he generously desired Mr. Creighton to be included, and thus the two are to share the proceeds, and to judge from the large circle of their acquaintances the proceeds will amount to something handsome.”

This would seem to be an indication of the depth of the friendship that Pearce and Creighton had developed, as well as suggesting that whatever Creighton had gotten in the way of financial considerations in 1860 was no longer coming his way in 1861. Benefit games were a polite and accepted way of raising money for an athlete in need without jeopardizing his amateur status. The Eagle estimated the crowd at between two and three thousand, which means that at 10 cents per ticket, Pearce and Creighton would have split between $200-$300 . . . not exactly a king’s ransom, but a buck went farther in the mid-19th Century.

The Eagle opined that Creighton “did not come up to his usual mark in pitching” in the first inning, giving up a pair of runs, but by the time the opposing team could score again, Creighton and Pearce’s squad had a 9-2 lead. The final score was 17-7, and no doubt many a fan in attendance had his appetite whetted for an 1862 season in which Jim Creighton and the Excelsiors would return to competitive play.

Who could have known that on that November afternoon, the young pitcher had only 346 more days to live?

Coming Soon:

Part 4: His final bow, and a transition into legend.

Sources:

Baseball in the Garden of Eden by John Thorn

Jim Creighton by John Thorn (SABR bio project at sabr.org)

Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the Nineteenth Century, edited by Bill Felber of the SABR Nineteenth Century Committee

Baseball’s First Inning by William J. Ryczek

Baseball Founders by Craig B. Waff, William J. Ryczek and Peter Morris

Searching for Jim Creighton by Thomas W. Gilbert (Base Ball, A Journal of the Early Game, Vol. 8 , edited by John Thorn)

The National Association of Baseball Players, 1857-70 by Marshall D. Wright

Digital editions of the New York Clipper, the New York Times and the Brooklyn Eagle