- Series: 1919 Black Sox Scandal

- Hall: J.G. Taylor Spink Award Recipient

Hugh Stuart Fullerton III (1873-1945) was one of the most respected sports journalists of the early twentieth century, introducing colloquial language and a human interest slant to the field. He was a mentor to at least two other all-time great sports scribes: Ring Lardner and Grantland Rice. He established his keen analysis of baseball stats early on when he projected one of the greatest World Series upsets, calling the 1906 tourney for the woeful-hitting White Sox over the 116-game winning Cubs in a crosstown rivalry for the ages. Yet, it wasn’t Fullerton’s on-field acumen that indelibly stamped his legacy on the game. The character-trait that shone most clearly was his integrity and zeal for the honor of the national pastime when, in 1919, Hugh refused to do what most in and outside the game did that year: duck and cover.

In blowing the whistle on what came to be known as the Black Sox scandal, Fullerton, aided by his ally Christy Mathewson, used his articles in the Chicago Herald-Examiner as a claxon, forcing the nation to face the existential threat posed by the vast network of underworld gamblers preying on players and the game itself. It took a year before his and Matty’s efforts bore fruit but, eventually, despite a widespread conspiracy of silence, charges were filed and eleven players were banned from baseball for life. No one was ever convicted of a crime, largely due to evidence that vanished quicker than a magician’s coin. Hugh was credited with shining the purifying light of investigative journalism at its finest on the threat. Baseball historian David Q. Voigt said, “In 1919 it was Fullerton’s detective work that unraveled the web of fact and rumor and exposed the crooked work of the Black Sox.” In a 1932 retrospective, Westbrook Pegler commented on the uniqueness of Fullerton’s contribution: “The fake world series of 1919 produced some of the worst newspaper reporting that the American press ever has been guilty of, and while all of us who were detailed to cover the show were not fired for missing the greatest sport story in 20 years is something that I have never understood. We were terrible.”

- Mathewson had covered the Series for a New York paper. He became Fullerton’s “expert witness,” parsing each key play for signs of wrongdoing

- Fullerton was a founder of the Baseball Writers Association of America. He is credited as the first of his field to include direct quotes of players in his coverage of the sport

- Elected to the Hall of Fame for Sportswriters via his selection for the J.G. Taylor Spink Award in 1946

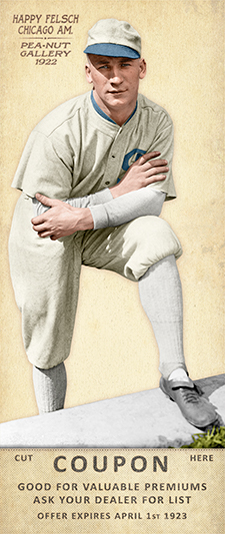

- Series: 1919 Black Sox Scandal

- City: Chicago

- Team: White Sox

- League: American League

Oscar Emil Felsch (1891-1964) was a sunny-tempered soul, the epitome of the hail-fellow-well-met. Born into the German community of Milwaukee, Felsch excelled at baseball and went on to become the star center fielder for the Chicago White Sox for six seasons spanning the most tumultuous era in franchise and baseball history. Charles Comiskey brought Hap to the Windy City in 1915 as part of one of the most successful rebuilding efforts in the game’s history. Felsch joined future Hall of Famer Eddie Collins and the incomparable “Shoeless” Joe Jackson, forming a club that would become a dominant force in the American League through the WWI years. Indeed, he forged the kind of career that Jim Nitz of SABR states might have been remembered “as one of the best all-around center fielders in baseball history.” He led his hard-hitting team in home runs and slugging, he was a league-leader in both offensive and defensive stats. And everybody loved Hap.

Years after the sordid story of the Black Sox had waned, Felsch, amiable as ever, was virtually the sole source for writer Eliot Asinof’s Eight Men Out. Hap was as humble as he was forthright in recounting his role in the scandal that shook baseball and ushered in the Judge Landis autocracy that forever changed the structure of the game. “I shoulda knew better,” moaned the aged and infirm former slugger. Earlier he had testified to foreknowledge and acquiescence to the gamblers’ schemes, but always denied actively trying to lose a game, much less the Series.

Despite his reputation for a very sociable demeanor, Felsch suffered under the indignities inflicted by miserly Comiskey. Injuries, his brother’s war wounds, his father’s illness, all took a toll as well in 1919, as did the clubhouse friction between players riven by the war effort. Felsch, Jackson and others had taken defense-industry jobs in ‘18 while others had enlisted. Rivalries erupted and friendships were damaged. Into the tensions stepped unctuous underworld minions of east coast mobsters. The resulting scandal enmeshed Felsch and he never pretended innocence.

- After being ousted from organized ball by Landis, Felsch endured years of litigation mingled with varying efforts to play ball. Eventually he went north and enjoyed success in Canadian circuits while always maintaining the love and support of his hometown

- Series: Athletic of Philadelphia: 1874

- City: Philadelphia

- Team: Athletics (NAPBBP)

- League: National Association (NAPBBP)

Weston Dickson Fisler (1841-1922) was a century too late to fire the shot heard round the world, but the Philadelphia infielder did strike the first blow in a different kind of American Revolution. On April 22, 1876, in the inaugural game of the new National League, the Boston Red Stockings (Red Caps) played Fisler’s Athletics at the Jefferson Street Grounds and Wes scored the first run. It was fitting that such a moment was shared by teams from the two cities most associated with the founding of the nation. And so it was that America celebrated its first centennial with the birth, in Philadelphia, of modern major league baseball.

Fisler grew up in neighboring Camden, N.J., the son of its mayor. At 5’6” and a mere 136 lbs, Fisler was a super-utility "tenth man" with the A’s, playing in 273 games across six seasons, mostly at 1st, 2nd & in the outfield. He had debuted in 1871, the season his team won the first and most controversial championship in the five year history of the National Association (NAPBBP). That pennant wasn’t decided until months after the season ended, when Harry Wright’s Bostons were deprived of their flag by vote of the owners at a November meeting hosted by the liquor-barons who owned the Athletics - a meeting in which their product flowed freely.

- Fisler retired after the ‘76 season with an excellent .310 average, with two HRs, and 189 RBI in his 273 games.

- Series: Beginnings: 1880's

- City: Cincinnati

- Team: Red Stockings (AA)

- League: American Association

Francis John Fennelly (1860-1920) came out of Fall River, MA to whack 34 career home-runs in the American Association. Not a bad sum for the era of flabby, misshapen baseballs. And, thanks to careful research, Frank’s effectiveness swinging a stout wooden implement does, indeed, exceed the prowess of his classmate and more famous hometown slugger, Lizzie Borden. Despite the scurrilous playground rhyme to the contrary, Lizzie used only about 30 blows to become the most famous self-made orphan in New England. Frank’s more prosaic career took him to Washington as a rookie with the Nationals in 1884 where he led the team in batting as their shortstop. He finished his debut year with Cincinnati where he hit .352 and earned his keep until traded to the Athletics during the ‘88 season. A brief stint with the Brooklyn Gladiators in 1890 concluded his major league experience. Overall, Fennelly’s BA was .257 with 175 stolen bases. He led the American Association in RBI (89) in 1885.

- The notorious axe murders occurred in 1892; two years after Frank returned home

- Frank was born six months before Lizzie, who outlived him by seven years

- Frank is buried in St. Patrick’s Cemetery; Lizzie is buried in Oak Grove Cemetery, next to her parents

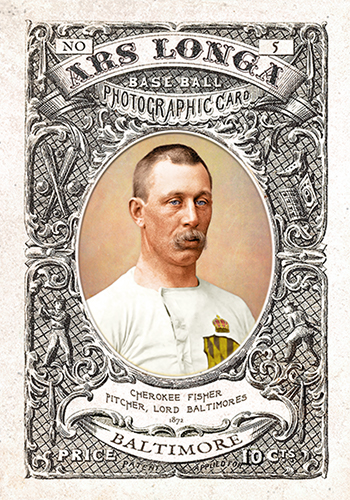

- Series: Mort's Reserve

- City: Baltimore

- Team: Canaries

- League: National Association (NAPBBP)

William Charles Fisher (1844-1912) was an erratic pitcher in baseball’s earliest days. He set some records with his renowned fastball but ended his career with far more losses than wins (56-84). Fisher toiled for so many clubs in the sport's beginnings that his resume reads like a catalog of the founding franchises. In the amateur days of the late 1860s, Cherokee threw for the West Philadelphias, the Cincinnati Buckeyes, the Troy Haymakers and the Chicago Dreadnaughts. As baseball turned pro, Fisher made the rounds, first with the Rockford Forest Citys in 1871 and then with such noteworthy teams as the Baltimore Canaries, Philladelphia Athletics and White Stockings, Hartford Dark Blues, Cincinnati Reds and Providence Grays. He posted the National Association’s best ERA in ‘72, 1.80, with Baltimore. Another less illustrious moment came with Chicago’s White Stockings in 1876, the first season for the new National League, when Cherokee surrendered the first home run in league history to Ross Barnes. Despite his mediocre win/loss record, Fisher ended his career with a fine 2.61 ERA. His finale came with Providence in ‘78 where his dismal 4-21 record ushered him out of the big leagues. Even then he managed a 3.06 ERA. It has been asserted that Fisher struggled throughout his tenure in baseball with a severe drinking problem. While that was a common affliction in his day, his history indicates he wasn’t out of control as he served for many years with the Chicago Fire Department following his major league days. Fisher’s peripatetic ways have been cited as a product of his alcoholism, but players were chattel in those days and clubs could and did ship even good players around arbitrarily.

- Fisher was 10-1 with Baltimore for his best winning percentage. His most wins came with Philadelphia in 1875 when he won 22 while losing 19. This was also the only other season he posted a winning record

- A quote concerning Fisher’s victory over New Haven in May of 1875 is a reminder of the far different conditions that prevailed in the early days: “Fisher’s pitching seemed to bother the New Haveners some, and foul outs and outs on strikes were frequent” per the New Haven Register