- Series: 1919 Black Sox Scandal

- City: Chicago

- Team: White Sox

- League: American League

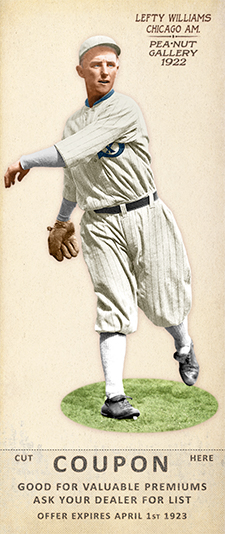

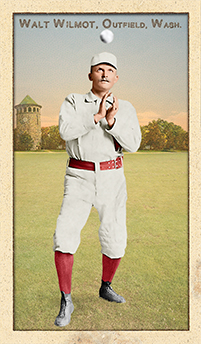

Claude Preston Williams (1893-1959) was the third Black Sox player to confess and the first to hear the jury say “Not Guilty,” sparing him from prison but dooming him to a life of shame. Lefty was being groomed to become the White Sox ace and had consistently challenged Cicotte for that unofficial designation throughout the fateful 1919 season. But teammate Chick Gandil’s blandishments lured Williams into the scandal that would forever taint the talented Chicago squad. By the time the Pale Hose finally won another pennant in 1959, Lefty was a month from death. The press noted that he was unable to celebrate, being “tired and aging and ill and sick at heart.” On pace to be an elite southpaw of the 1920s, Lefty Williams instead became a man broken by his betrayal of the game at which he excelled.

Lefty had come up with the Tigers as a kid in 1913, but floundered and was sent to the Pacific Coast League. He starred for the Salt Lake City Bees in ‘15, earning a trip back to the majors when Charles Comiskey purchased his contract. Williams validated the owners’ judgment by helping lead the team to the 1917 pennant with a 17-8 record. The following year was a lost cause for MLB with the war on and the government calling up players. Many, including Williams and his pal Joe Jackson, sought shipyard jobs to escape the draft. This became a wedge within teams and perhaps none more than the Sox. Labeled as “unpatriotic,” the “work or fight” players who chose defense jobs were vilified by management and teammates alike.

Nevertheless, in 1919 Comiskey welcomed his charges back to the fold. Williams was stung by the owner’s stiffing him of his final ‘18 paycheck, adding to an aggrieved mindset. Gandil found an all-too-willing mark when he peddled his scheme to throw the Series that everyone knew the White Sox would be in. Overcoming wildness that plagued his early years, Lefty was terrific that year with a 23-11 record and 2.64 ERA. His remarkable control made his World Series performance all the more notorious. He logged a record three losses and curried trouble every start with a rash of bases on balls. The only other pitcher to lose three games in a Series is George Frazier of the Yankees, who equaled Lefty’s dubious feat in 1981.

- Williams expressed remorse even before the Series ended. Some believe he was threatened by mobsters. Having already received $5,000 mid-Series, he later admitted “I was sorry. I wanted to be out of it and not mixed up in it at all.”

- Series: 1919 Black Sox Scandal

- City: Chicago

- Team: White Sox

- League: American League

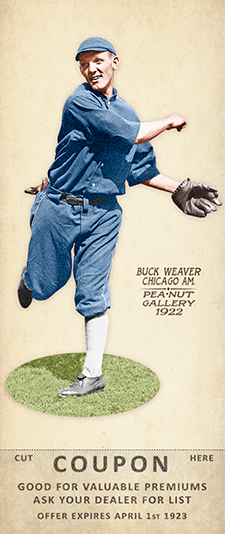

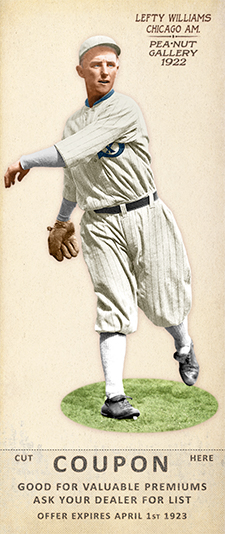

George Daniel Weaver (1890-1956) climbed to a lofty height during his baseball career and plummeted to an historic low that would test any man. Buck’s dad insisted he forego his mother’s funeral to begin his pro career in the White Sox system. He ended his career when Judge Landis banished him from the game along with 7 fellow Sox. In between, this gregarious, cheerful soul basked in the shadows of the Great Pyramid sporting a fez during the 1913 world tour and danced for joy after Comiskey’s club locked up the ’17 Series, a team he had led in batting and afield. Although pilloried with his teammates for throwing the 1919 Series, Weaver played errorless ball, hit .324, and was never accused of taking money. He would spend the rest of his life trying to clear his name. After Cicotte and Jackson confessed, the Sporting News headlined: “Chicago Fans Grieve Most for Weaver and Still Hope for Him.”

- Played exclusively for the White Sox (1912-1920), averaging .272, and was the only banned player to remain in Chicago

- Buck successfully sued his penurious owner for his 1921 salary

- Series: Beginnings: 1880's

- City: Louisville

- Team: Colonels

- League: American Association

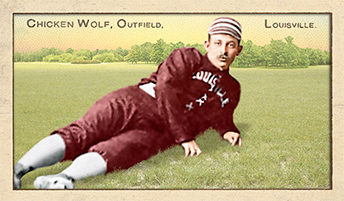

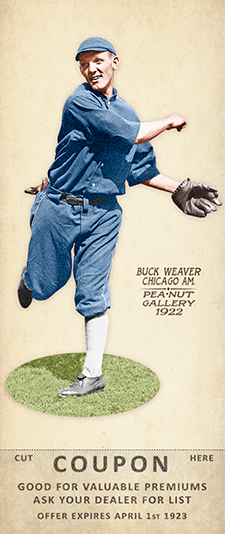

William Van Winkle “Jimmy” Wolf (1862-1903) played virtually his entire career with Louisville, starting in 1882 when the club was known as the Eclipse and continuing with the Colonels through the 1891 season. He played three games for the Browns in ‘92 before heading, for the first time, to the minors for three campaigns. Known mostly as Jimmy, Wolf had the Chicken moniker hung on him by teammate Pete Browning after Wolf gorged on a pre-game boiled bird and committed several errors that day. By any name, Wolf earned a renown that has since eluded him. He was, arguably, the best hitter in the history of the American Association, and is the league's all-time leader in games played, hits, doubles, triples and total bases. The second-class status of the 19th century’s “junior circuit” has always weighed heavily in Cooperstown evaluations. Jimmy reached his pinnacle in 1890, hitting .363 and leading the post-season tourney with .360 and eight RBI. The right-hander was primarily an outfielder, but eventually saw action at every position. The previous year had immersed Wolf in the most controversy of his career. A feud with manager Dude Esterbrook led to Wolf replacing him. Jimmy faithfully carried out owner Mordecai Davidson’s tough fine schedule for on-field lapses. Things erupted into the first players’ strike and Davidson sold the club mid-summer with Wolf ending his managerial career.

- The trials and tribulations of the 1889 season swirled around Wolf and his hapless teammates en route to a spectacularly dismal record of 27-111. No surprise that tempers flared and fights broke out. Davidson’s obstinance, particularly his penchant for dunning his players, exacerbated the situation. It is to Wolf’s credit that he persevered while holding the captain’s reins and, despite the bad blood, his teammates embraced him once Davidson was gone

- Wolf was intrepid on the ball field and off. In retirement he served as a firefighter in his hometown of Louisville. His tragic death at age 41 resulted from a traumatic brain injury incurred a few years prior to 1903. Wolf was buried beside childhood friend and comrade in arms, Pete "The Louisville Slugger" Browning

- William Van Winkle Jimmy Chicken Wolf. I just had to write that again.

- Wolf enjoys five known poses in the Old Judge canon

- This card of Chicken Wolf represents the 300th and final card in the 1880s: Base Set

- It is truly gratifying to close this series on such a high and symbolic note . . . .

- with an elusive player of some magnitude whom I have been yearning and struggling to get into the series for four years now (this is my fourth attempt at Chicken Wolf as his images are scarce and typically of poor quality)

- who has a name so deep in the alphabet (only 5 OJ subjects follow Wolf alphabetically: Dandy Wood, Pete Wood, Harry Wright, Chief Zimmer & Frank Zinn - with Zinn being the only one to escape this series' reach)

- and with an OJ pose of such repose. Wolf's halfhearted enactment of a slide while resting on a tuft of carpeted grass strikes me more as somebody who is resting after a hard-fought and victorious campaign in the field of dreams . . . . and that is exactly how I feel in bringing this series to a close.

- The first release of this 300th & final card, on August 10, 2017, is the 2,068th card to be made and released from the 1880s: Base set

- I sold the first card from this series, Doc Bushong, on May 8, 2013, for $11.62 to a brave and courageous soul in Wind Gap, Pennsylvania

- I could not have gotten here from there without each and every one of you. Thank you, sincerely, for your tremendous support.

- The journey continues . . . . .

- Series: Beginnings: 1880's

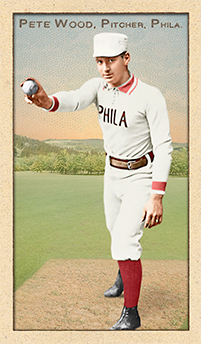

- City: Philadelphia

- Team: Quakers

- League: National League

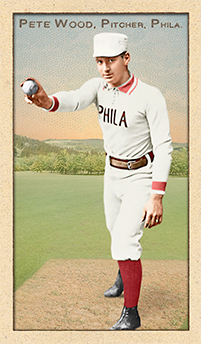

Peter Burke Wood (1867-1923) got into the majors with the Buffalo Bisons in 1885, just in time to join his brother Fred as an early family combo in the big leagues, and rarer still to be teammates. Fred retired after that season. Pete was a native of Ontario Canada and had begun ‘85 with two Hamilton teams just across the river from Buffalo. Wood would shuttle back and forth over Niagara playing for Buffalo’s International League entry in ‘86 and the Hamilton Clippers of the IL and the Hamilton Hams of the International Association through the 1888 season. He got one more call-up with the Philadelphia Quakers in 1889, but saw action in a mere three games where he failed to get a hit but did manage to drive in two runs. Pete returned to Canada for his final seasons with the London Tecumsehs and Toronto Canucks. Throughout his time in pro ball Wood had alternated between pitching and infield/outfield. He was 8-15 with Buffalo in ‘85 and had one stand-out season in the pitcher’s box with the Hams in ‘88, winning 37 and losing 12. He may have hurt his arm in that remarkable year as he rarely pitched again. Nevertheless, his performance undoubtedly gained him that final shot in the majors, but he was only able to win one of his two starts for the Quakers. His victory came against the Indianapolis Hoosiers where Philadelphia won 11-4 beating Charlie Getzien.

- MLB.com compiled a list: Brothers as teammates in MLB history. They found nearly 100 such duos (including some trios--looking at you Alou and Cruz brothers….) Although the compilation extends into the 19 century, the Wood brothers are absent

- Baseball Almanac has identified over 350 brother combinations to have made the majors. Perhaps the record goes to the Delahanty clan who put five siblings into the bigs

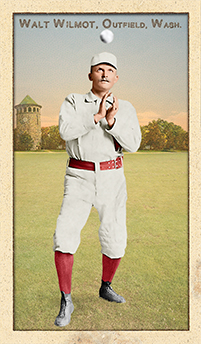

- Series: Beginnings: 1880's

- City: Washington, D.C.

- Team: Nationals

- League: National League

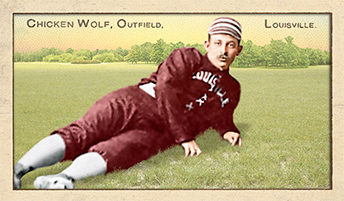

Walter Robert Wilmot (1865-1929) was a switch-hitting outfielder who played for three teams over a ten-season major league career. The high-point of his tenure came in 1894, a wondrous year for hitters in general. The second season after the mound moved to 60' 6'' saw output the likes of which have not been seen before or since. Wilmot far exceeded his normal average, hits and RBI and scored 136 runs - a total that would have placed him in the NL's top-ten any other year of the decade and beyond. But the likes of Hugh Duffy, Billy Hamilton, Joe Kelley and Wee Willie Keeler were setting baseball's world on fire.

That year Hamilton's Phillies fielded the strongest-hitting outfield of all-time, averaging over .400 with sub Tuck Turner exceeding even Billy, Ed Delahanty and Sam Thompson. So where did the mighty slugging Phil's wind up? In fourth place trailing the legendary Orioles by 18 games. But it was in runs-scored that '94 stood out. In most years of the era, one or two teams might barely plate a thousand runners. But in 1894 five teams blew past that mark and four others nearly hit it. Overall, the National League squads averaged an all-time high 7.36 runs per game.

All of this left Wilmot with an outstanding also-ran year for the ages, batting .330 with 197 hits, 134 runs and 130 RBI in just 133 games. Walt broke in with Washington in 1888, spent the first half of the nineties in Chicago and wrapped up with the Giants in 1897-98. He led the NL in triples in '89 and the following campaign tied for the HR lead.

- Wilmot was the first batter to walk six times in a game (8.22.1891)

- He played beside Dummy Hoy in D.C.'s outfield

- In addition to his decade in the majors, Walt played eight minor league seasons beginning with St. Paul in 1886 and ending in Butte, MT of the Pacific National League in 1904

- His MLB stats include a .276 average with 92 triples

- Wilmot’s uniform color on this card was changed in July, 2017 from blue to red to reflect recent reliable research by Craig Brown & friends at Threads of Our Game. One card was previously released featuring a blue uniform.