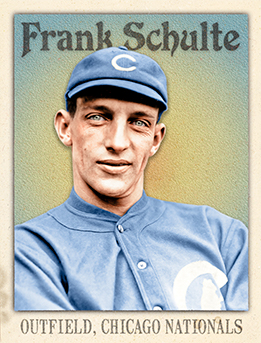

- Series: Diamond Heads '15

- City: Chicago

- Team: Cubs

- League: National League

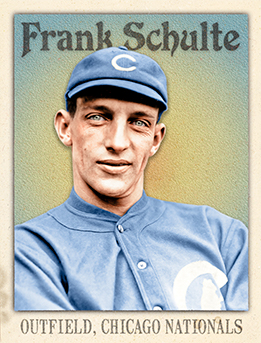

Frank M. Schulte (1882-1949) played for his local minor league franchise, the New York State League’s Syracuse Stars, for three years before being discovered by the National League’s Chicago club, who bought his contract and brought him up at the end of the 1904 season. The team was being called the “Cubs” by sportswriters, a name that wouldn’t be official until 1907. By any name, “Wildfire” Schulte made a big impact. He was a solid-hitting outfielder who became a mainstay in West Side Park's outfield as the Cubs won four pennants and two World Series during his long tenure. Frank must have really liked the play “Wildfire” he once saw in Mississippi: He named his racehorse after the play and would earn the sobriquet for himself by teammates who clearly appreciated his spirit.

Schulte’s above average hitting (career 115 OPS+) was reliable, but he proved particularly clutch in the post-season, where he averaged .321 across 21 World Series' contests. Such fortuitous timing would further Schulte's legacy in yet another remarkable achievement: his spectacular campaign of 1911 just-so-happened to coincide with the inaugural presentation of the Chalmers Award; essentially MLB's very first MVP award, which was gifted to the "most important and useful player to the club and to the league." The prior season, Hugh Chalmers decided to spark car sales for his automotive company by offering a new model to the players with the highest batting averages in each league. The ensuing fiasco involving Ty Cobb and Nap Lajoie prompted Chalmers to revise the award in 1911 to be gifted to the leagues' “MVPs” and Schulte's career year-for-the-ages couldn't have been better timed.

Schulte’s 1911 MVP Award season:

- 154 games, 105 runs, 173 hits, 30 doubles, 21 triples, league-leading 21 HR, 107 RBI, 23 stolen bases, league-leading .534 slugging, league-leading OPS+ 156, league-leading 308 total bases

- With the performance, Schulte became the first person in MLB history to have 20 or more doubles, triples, home runs and stolen bases in the same season

- Schulte's achievement would stand unmatched for 46 years, until Willie Mays duplicated the feat in 1957

- Schulte earned his nickname by a ferocious approach to base running that saw him steal home 22 times

- Famed shortstop Joe Tinker’s Chicago career spanned Wildfire’s and Schulte inspired Tinker to speculate that no “quainter or more original character ever existed in the National Pastime.” One eccentricity was Schulte’s penchant for scouring the sidewalks looking for hairpins, auguring success at the plate.

- Another testimony to Frank’s batting prowess was his thirteen-game hit streak during his four World Series appearances, which still ranks him fourth all-time, tied with Harry Hooper and Derek Jeter

- Schulte closed out his time in Chicago with the 1916 season. He spent the next three years with three teams and went on to play in the International League and Pacific Coast League through 1922 before retiring to live in Oakland, CA

For a brief but wonderful account of the history of the Chalmers Award, including a review of the events of 1910 surrounding the controversy between Ty Cobb & Nap Lajoie, check out this Ars Longa guest blog post by Van Nightingale: Did They Get it Right?

- This card is not included in the 100-card Diamond Heads '15 base set.

- This card is one of the rewards you receive for completing the Ars Longa Clubhouse Challenge: Chalmers Awards Winners

- This card is exclusive to that challenge, is gifted freely to winners of the challenge, and is neither bartered nor sold otherwise by Ars Longa.

- This is one of two such Diamond Heads '15 Clubhouse Challenge reward cards. The other is Franklin Pierce Adams.

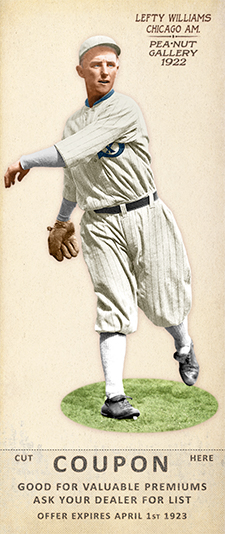

- Series: 1919 Black Sox Scandal

- City: Chicago

- Team: White Sox

- League: American League

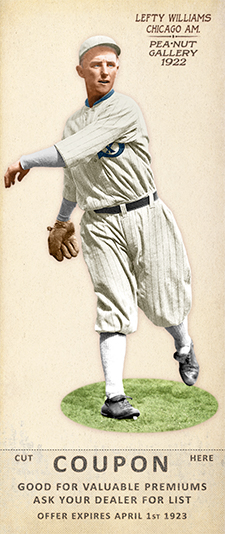

Claude Preston Williams (1893-1959) was the third Black Sox player to confess and the first to hear the jury say “Not Guilty,” sparing him from prison but dooming him to a life of shame. Lefty was being groomed to become the White Sox ace and had consistently challenged Cicotte for that unofficial designation throughout the fateful 1919 season. But teammate Chick Gandil’s blandishments lured Williams into the scandal that would forever taint the talented Chicago squad. By the time the Pale Hose finally won another pennant in 1959, Lefty was a month from death. The press noted that he was unable to celebrate, being “tired and aging and ill and sick at heart.” On pace to be an elite southpaw of the 1920s, Lefty Williams instead became a man broken by his betrayal of the game at which he excelled.

Lefty had come up with the Tigers as a kid in 1913, but floundered and was sent to the Pacific Coast League. He starred for the Salt Lake City Bees in ‘15, earning a trip back to the majors when Charles Comiskey purchased his contract. Williams validated the owners’ judgment by helping lead the team to the 1917 pennant with a 17-8 record. The following year was a lost cause for MLB with the war on and the government calling up players. Many, including Williams and his pal Joe Jackson, sought shipyard jobs to escape the draft. This became a wedge within teams and perhaps none more than the Sox. Labeled as “unpatriotic,” the “work or fight” players who chose defense jobs were vilified by management and teammates alike.

Nevertheless, in 1919 Comiskey welcomed his charges back to the fold. Williams was stung by the owner’s stiffing him of his final ‘18 paycheck, adding to an aggrieved mindset. Gandil found an all-too-willing mark when he peddled his scheme to throw the Series that everyone knew the White Sox would be in. Overcoming wildness that plagued his early years, Lefty was terrific that year with a 23-11 record and 2.64 ERA. His remarkable control made his World Series performance all the more notorious. He logged a record three losses and curried trouble every start with a rash of bases on balls. The only other pitcher to lose three games in a Series is George Frazier of the Yankees, who equaled Lefty’s dubious feat in 1981.

- Williams expressed remorse even before the Series ended. Some believe he was threatened by mobsters. Having already received $5,000 mid-Series, he later admitted “I was sorry. I wanted to be out of it and not mixed up in it at all.”

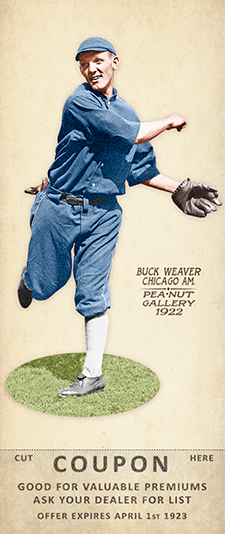

- Series: 1919 Black Sox Scandal

- City: Chicago

- Team: White Sox

- League: American League

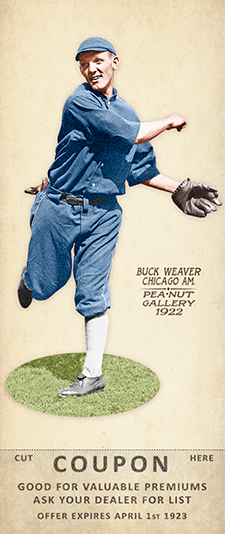

George Daniel Weaver (1890-1956) climbed to a lofty height during his baseball career and plummeted to an historic low that would test any man. Buck’s dad insisted he forego his mother’s funeral to begin his pro career in the White Sox system. He ended his career when Judge Landis banished him from the game along with 7 fellow Sox. In between, this gregarious, cheerful soul basked in the shadows of the Great Pyramid sporting a fez during the 1913 world tour and danced for joy after Comiskey’s club locked up the ’17 Series, a team he had led in batting and afield. Although pilloried with his teammates for throwing the 1919 Series, Weaver played errorless ball, hit .324, and was never accused of taking money. He would spend the rest of his life trying to clear his name. After Cicotte and Jackson confessed, the Sporting News headlined: “Chicago Fans Grieve Most for Weaver and Still Hope for Him.”

- Played exclusively for the White Sox (1912-1920), averaging .272, and was the only banned player to remain in Chicago

- Buck successfully sued his penurious owner for his 1921 salary

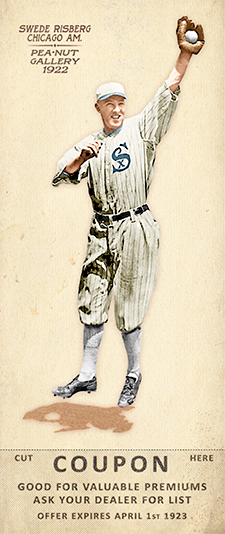

- Series: 1919 Black Sox Scandal

- City: Chicago

- Team: White Sox

- League: American League

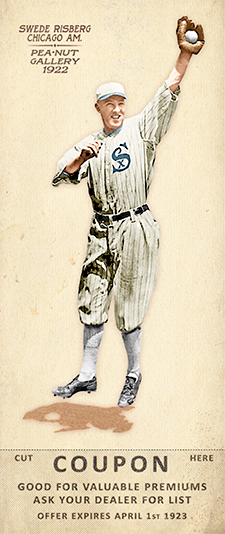

Charles August Risberg (1894-1975) grew up on the streets of San Francisco, dropping out of school in the third grade. He had a flair for baseball and, when he switched to shortstop, he blossomed into a defensive star worthy of a call-up to the White Sox in 1917. Swede’s minor league experience foreshadowed the future outlaw character he would display almost from his arrival in the big leagues. In 1913, when Risberg traveled to the LA area to play in the Pacific Coast League, he was drawn to the Vernon/Venice Tigers. At that time these were the only communities in Los Angeles county that were “wet.” Booze was the defining identifier for owner Pete Maier’s club. When it was in Vernon fans could enter the park directly from Doyle’s bar.

Risberg made the big club based on his defense, but hit so poorly in his rookie season that he only got two pinch hitting appearances in the ‘17 Series when the Sox beat the Giants. Swede returned to California for part of the 1918 season, escaping the draft by taking a shipyard job that amounted mostly to playing semi-pro ball for the company during that “work or fight” year. By his own testimony, Swede was crooked throughout his major league tenure, all with Chicago. He claimed to have been the organizer of a scheme in 1917 to bribe Tiger players to throw some games. And he was at the center of the Black Sox Scandal in 1919. Later many would assert that, despite the clear conspiracy with gamblers, the Reds won fair and square although they were thought to be far inferior to Chicago. It is difficult to make a case from the players’ performance. Risberg would be an exception. He apparently threw himself into the fix with zeal, committing a record eight errors and going 2 for 25 at bat. And his reported payout of $15,000, which was more than four times his salary, was a far bigger reward than others realized. He may have earned his bonus because he served as an enforcer. Joe Jackson received a death threat from Risberg if he “blabbed.” Shoeless Joe would later describe Swede as a “hard guy.”

- True to his scofflaw nature, Risberg defied Judge Landis’ ban and played exhibition ball for years. As the youngest of the “Eight Men Out,” and having a very brief tour in the majors, he had incentive to play wherever he could

- It may be that the game he tarnished got its revenge. Swede had been spiked in Chicago and the wound never properly healed. He lost the leg in his old age, dying in a nursing home in Redding, CA on his 81st birthday

- Series: 1919 Black Sox Scandal

- City: Chicago

- Team: White Sox

- League: American League

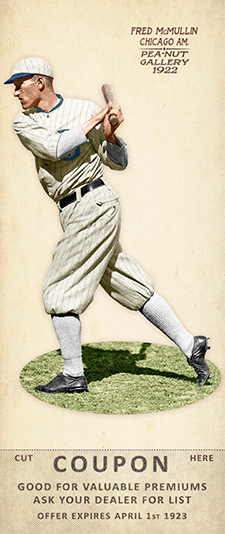

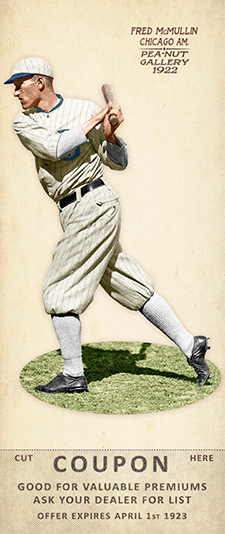

Fred Drury McMullin (1891-1952) has been called the “forgotten man” of the Black Sox. Writing for SABR, Jacob Pomrenke called McMullin the "Eighth Man Out, the most obscure of the White Sox players who agreed to throw the 1919 World Series to the Cincinnati Reds."

As a nondescript utility man with little promise to impact the series, Fred would certainly seem to be the unlikeliest member of that talented team to be pursued and paid off by gamblers. Some have suggested that, as the team’s scout, Fred may have contributed to the scheme by providing misleading information to his teammates about Reds hitters and pitchers. Or perhaps, as it is most commonly suggested, McMullin implicated himself in the scandal when he allegedly overheard talk of throwing the Series and insisted on his inclusion in the conspiracy. And yet Ed Cicotte testified that "the idea of the fix had originated in a conversation with Gandil and McMullin." Like so many mysteries that will forever envelope the 1919 Black Sox, the truth of how and why Fred McMullin was involved in the scandal may never be known.

McMullin had come out of West Coast ball where he impressed the Tigers enough to give him an audition at the end of the 1914 season. Fred languished on the bench, watching the likes of Cobb and Crawford before getting his only appearance that year in Fenway, mopping up a Red Sox laugher and striking out in his only at-bat. Returning to California allowed Fred to build his resume and the White Sox signed him for the ‘16 campaign. Again, he joined a stacked team with little chance of breaking into the lineup. In 1917, McMullin got into late-season games and did well; especially helping with his defense in the Series against the Giants, which the Sox won. Fred used his $3,600 bonus to buy a small house.

Following the war-shortened ‘18 season, the White Sox were again a dominant force in 1919. Owners feared the year would be a loss in the war’s aftermath and scheduled another truncated schedule which included smaller player paychecks. In the lead-up to the postseason, Chick Gandil seems to have led the conspiracy that would ensnare Fred and six more teammates.

- McMullin stayed mum the rest of his life concerning the fix

- Unlike his teammates, Fred didn’t try to barnstorm, but he did play some semi-pro ball in LA - until Irish Meusel was fined $100 by the Phillies for playing against him

- McMullin ended his working life in law enforcement, as a court marshal in Los Angeles, and died on the job from a stroke