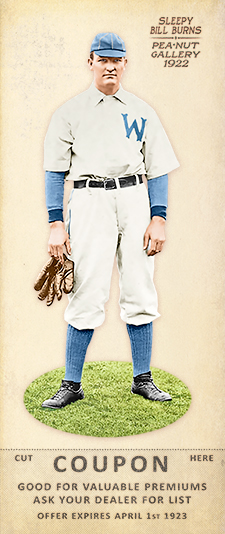

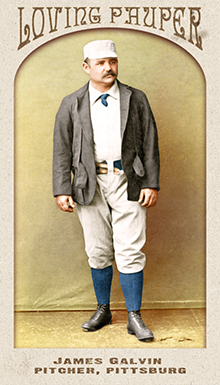

- Series: 1919 Black Sox Scandal

- City: Washington, D.C.

- Team: Senators

- League: American League

William Thomas Burns (1880-1953) was an American League pitcher who didn’t finish well. He began his career of failed finales in his rookie season, 1908, with the Washington Senators. Bill took a no-hitter into the ninth inning and got two more outs before Germany Schaefer spoiled his bid and won the game. A year later with the White Sox, and facing his former teammate Walter Johnson, Burns lost another no-hitter with one out to go. Not until Dave Stieb had the misfortune of losing (consecutive!) two-out no-nos in 1988 would such a fate befall another major leaguer. The ‘08 season was a fine one for Bill, who apparently didn’t earn his “Sleepy” sobriquet until later, when he developed a reputation for a lackadaisical demeanor on the mound. He had an outstanding 1.69 ERA in 1908, but would never win more than eight games in a season en route to a 30-52 career record.

It was his career-ending tour with the Tigers in 1912 that would prove fateful for Sleepy Bill. On May 18, teammate Ty Cobb couldn’t resist battering a maimed and abusive fan, earning a suspension from league president Ban Johnson and triggering a walk-out by the team. Detroit’s owner wanted to forfeit and Johnson threatened to fine him if he didn’t field a team in Philadelphia. Thus Burns crossed paths with Billy Maharg, who was one of the replacement players against the Athletics. Years later, the two would team up in a scheme that provided the most notorious of endings for Bill Burns: the end of any reputation for honor in baseball. He and ex-boxer, and shadowy operator Maharg, likely at the behest of the most famed gambler of his day, Arnold Rothstein, would fix the 1919 World Series. Burns met with Eddie Cicotte and Chick Gandil at a New York hotel prior to the postseason. Investigation later revealed that Burns acted with Rothstein’s chauffeur, Maharg, and claimed to be representing someone known as “A.R.” For all of the rumors and speculation surrounding the Black Sox scandal, one bit of testimony was clear. Burns told the Assistant State Attorney: “I had the hundred thousand dollars to handle the throwing of the World Series. I also told them that I had the names of the men who were going to finance it.”

- Sleepy Bill, known for carelessness as a pitcher, was a willing henchman to the biggest crime lord of the era. He displayed a carelessness for the truth, for morality and integrity, forever staining America’s Pastime

- Another footnote to the Black Sox: Jean Dubuc was a player on the 1919 New York Giants (and had also been on the 1912 Tigers). Despite having an excellent year for the Giants in 1919, John McGraw released Dubuc, unexpectedly and without explanation, before the 1920 season. Dubuc then left the country to play and, in retrospect, lay low in Canada for 1921, and returned to play minor league ball in the States in 1922, but would never again play in the major leagues. When asked later why he had released Dubuc, McGraw stated that Dubuc "constantly associated" with Sleepy Burns and suspected that the two of them, along with Hal Chase, had conspired to ensure the Giants would lose out to the Reds during the 1919 pennant chase. Further raising suspicions of Dubuc's complicity in the year-end gambling scandals of 1919, his former Giants teammate Rube Benton testified in court during the Black Sox hearings that Dubuc had been tipped to the world series' fix by an anonymous telegram that urged him to place bets on the Reds. Combining that testimony with McGraw's suspicions, many (including The Sporting News) considered Dubuc's "guilty knowledge" of the fix as evidence of conspiracy equal to that of some other scandal participants, such as Buck Weaver and Joe Jackson, but Jean Dubuc somehow escaped such judgement from Kenesaw Mountain Landis and was never formally banned from professional baseball. Dubuc would hence go on to have a successful career as a scout for the Detroit Tigers, signing Birdie Tebbetts and Hank Greenberg. Nobody knows who sent Dubuc that anonymous telegram in 1919, but the most common candidate proposed by historians is Sleepy Bill Burns.

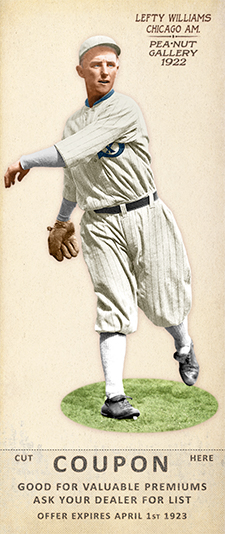

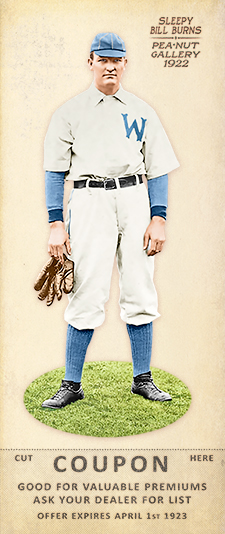

- Series: 1919 Black Sox Scandal

- City: Chicago

- Team: White Sox

- League: American League

Claude Preston Williams (1893-1959) was the third Black Sox player to confess and the first to hear the jury say “Not Guilty,” sparing him from prison but dooming him to a life of shame. Lefty was being groomed to become the White Sox ace and had consistently challenged Cicotte for that unofficial designation throughout the fateful 1919 season. But teammate Chick Gandil’s blandishments lured Williams into the scandal that would forever taint the talented Chicago squad. By the time the Pale Hose finally won another pennant in 1959, Lefty was a month from death. The press noted that he was unable to celebrate, being “tired and aging and ill and sick at heart.” On pace to be an elite southpaw of the 1920s, Lefty Williams instead became a man broken by his betrayal of the game at which he excelled.

Lefty had come up with the Tigers as a kid in 1913, but floundered and was sent to the Pacific Coast League. He starred for the Salt Lake City Bees in ‘15, earning a trip back to the majors when Charles Comiskey purchased his contract. Williams validated the owners’ judgment by helping lead the team to the 1917 pennant with a 17-8 record. The following year was a lost cause for MLB with the war on and the government calling up players. Many, including Williams and his pal Joe Jackson, sought shipyard jobs to escape the draft. This became a wedge within teams and perhaps none more than the Sox. Labeled as “unpatriotic,” the “work or fight” players who chose defense jobs were vilified by management and teammates alike.

Nevertheless, in 1919 Comiskey welcomed his charges back to the fold. Williams was stung by the owner’s stiffing him of his final ‘18 paycheck, adding to an aggrieved mindset. Gandil found an all-too-willing mark when he peddled his scheme to throw the Series that everyone knew the White Sox would be in. Overcoming wildness that plagued his early years, Lefty was terrific that year with a 23-11 record and 2.64 ERA. His remarkable control made his World Series performance all the more notorious. He logged a record three losses and curried trouble every start with a rash of bases on balls. The only other pitcher to lose three games in a Series is George Frazier of the Yankees, who equaled Lefty’s dubious feat in 1981.

- Williams expressed remorse even before the Series ended. Some believe he was threatened by mobsters. Having already received $5,000 mid-Series, he later admitted “I was sorry. I wanted to be out of it and not mixed up in it at all.”

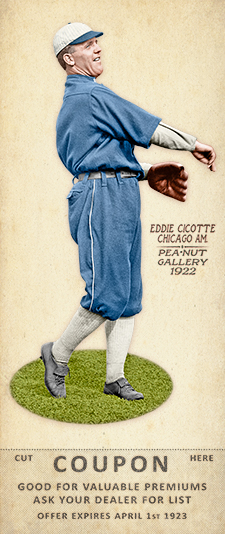

- Series: 1919 Black Sox Scandal

- City: Chicago

- Team: White Sox

- League: American League

Edward Victor “Knuckles” Cicotte (1884-1969) won 208 games and a World Series with the White Sox in 1917. The Sporting News said in 1918 that “Perhaps no pitcher in the world has such a varied assortment of wares….” But it was Eddie’s first pitch of the 1919 Series that plunked Morrie Rath in the back and signaled the fix was in. No one was ever convicted of the infamous Black Sox scandal but Cicotte, with seven teammates, never played ML ball after his tearful confession following the ’20 season.

- Cicotte, Shoeless Joe, and other banned Sox players went on to barnstorm under false names

- His mastery of the knuckleball led to a transformation of his career. His control improved to the point of walking only 89 in 572 innings in 1918/19 combined.

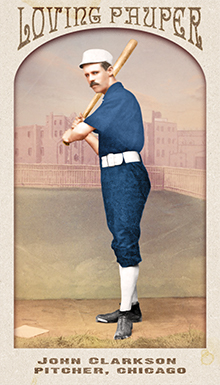

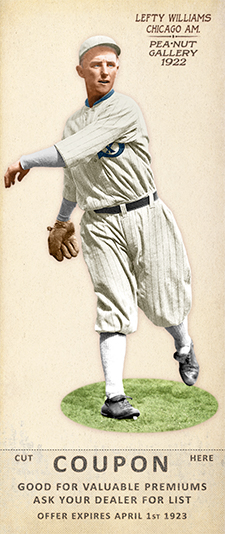

- Series: 1880s: Loving Paupers

- City: Chicago

- Team: White Stockings

- League: National League

- Hall: National Baseball Hall of Fame

John Gibson Clarkson (1861-1909) won 328 games, won the triple crown in 1889 and twice pitched more than 600 innings in a season. In 1885, John appeared in 70 games, threw 68 complete games, 623 innings, won 53, had an ERA of 1.85, a no-hitter, and won the pennant. Apparently having to hurl the sphere a mere fifty feet was a tonic to the arm. But unlike so many pitchers of his era, Clarkson didn’t flame out from such prodigious labor on the mound. From 1885-92 he AVERAGED 36 wins per season and would win 30+ an extraordinary six times. This great career began with the Worcester Ruby Legs in 1882, flowered with Cap Anson’s Sox in ‘84 and fully bloomed in Boston when John followed his ace catcher King Kelly to the Beaneaters in ‘88. League politics that culminated in the Players’ League revolt took a toll on Clarkson’s reputation and sundered his friendship with Kelly as the hurler remained loyal to the Nationals.

- Cleveland acquired John in 1892 allowing him to team with Cy Young. Chief Zimmer, who caught Young for a decade, proclaimed Clarkson the best he ever saw

- Elected to Hall of Fame: 1963

Auction History

Cartophilia

Old Judge Pose: 78-7

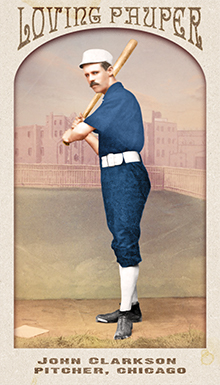

- Series: 1880s: Loving Paupers

- City: Pittsburgh

- Team: Alleghenys

- League: National League

- Hall: National Baseball Hall of Fame

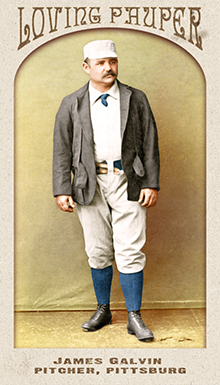

James Francis Galvin (1856-1902) sported some colorful nicknames: Pud, Gentle Jeems and The Little Steam Engine, indicative of his renown. Pud was baseball’s first 300-game winner. He pitched for six teams over 15 years, and remains the only player to win 20+ games in ten seasons and not win a pennant. Only Cy Young pitched more innings or hurled more complete games, a testimony to the extraordinary demands placed on starters in the 19th century. Perhaps no pitcher of any era accomplished so much by overcoming a distinct physical limitation. In Galvin’s case, it was his small hands which left him unable to completely grip a baseball. He couldn’t throw the curve so he adapted, becoming an expert in “drops, straight balls and the different artifices known to pitchers to deceive the batter” as he told a friend. As his steam engine nickname suggests, Pud just rolled right at the hitter with power and durability yet with amazing finesse, especially in holding runners on base. Buck Ewing was a great admirer and said he wouldn’t have had anyone attempting steals with Galvin on the mound.

- Galvin threw no-hitters in 1880 and ‘84

- Began and ended his long career in St Louis with the NA’s Brown Stockings and NL’s Browns

- Elected to Hall of Fame: 1965

Auction History

Cartophilia

Old Judge Pose: 177-2