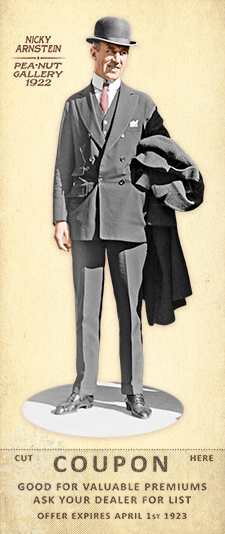

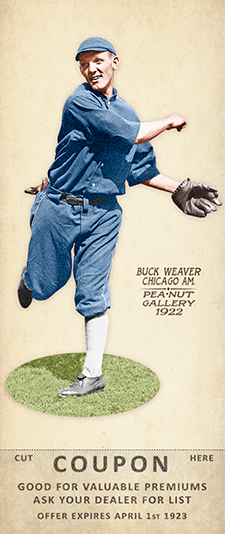

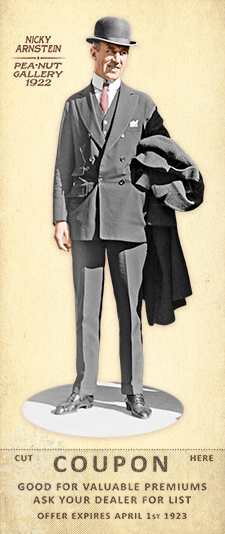

- Series: 1919 Black Sox Scandal

Julius Wilford Arnstein (1879-1965) was a dashing 6’6” charmer, capable of so beguiling his rich and beautiful friends that they never saw his cons coming. Born in Berlin to a Jewish father and raised in New Jersey as an Episcopalian, Arnstein seems to have embraced that duality as he spent much of his life on each side of the law. “No boy could have been brought up with more love and care than was I,” he recalled. He bemoaned that his love for “the beautiful things of life” was overshadowed by his “fondness for the cards, the dice, and the horses.” He plied the trade of riverboat gambler on the high seas, fleecing the cream of society on ocean liners and the casinos of the continent. He idolized his hero and mentor Arnold Rothstein and would gush about A.R.: "He was an honest man, with an outstanding integrity. He had daredevil courage.” This of the man who made Nicky his “admirer, partner and fall guy.”

As skilled as he was at entrancing his marks, Arnstein was blinded by his devotion to Rothstein. He hired A.R.’s famed legal eagle Bill Fallon, the “archetype amoral criminal defense lawyer” who guided Nicky to become perhaps the first defendant to “take the Fifth” in a securities theft case. Nicky beat the rap but, after the fatal gaffe of insulting Fallon, was convicted in a Federal trial with lesser counsel. Undoubtedly it was Nicky’s involvement with Rothstein that implicated him with the “usual suspects” - various gamblers and gangsters of the era - in the Black Sox scandal. If the standard for a “perfect crime” is that no one goes to jail, then the 1919 Series Fix fits the bill. Nobody spent a day in jail, but the National Pastime was severely tarnished and forever changed. Charles Comiskey forcibly disbanded one of the most talented teams of the deadball era, losing eight players to lifetime bans from the game, subsequently condemning one of the sport's all-time greatest stars of any epoch - Shoeless Joe Jackson - to permanent exile.

- Arnstein was famous for his lover and eventual wife, vaudeville queen Fanny Brice. She was faithful as he sat in Leavenworth but divorced him upon his release

- Nicky abandoned the criminal life following his second and final prison term in 1927, moved to LA and prospered. That nickname, by the way, is said to have come from the nickel-plated bike he road as a kid. For all his aliases, that one is the most prosaic

- Perhaps a fitting epitaph of Arnstein’s could be words used in Bill “The Big Mouthpiece” Fallon’s obituary: “his intelligence, eloquence and panache forever stand trial beside his immorality, dishonesty and self-indulgence.”

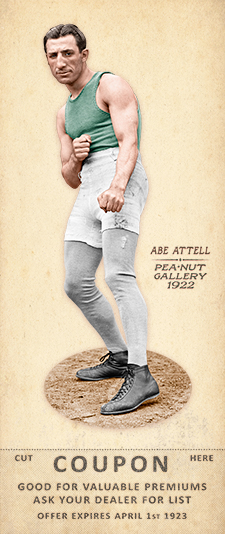

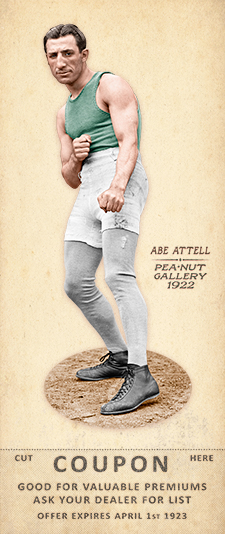

- Series: 1919 Black Sox Scandal

Abraham Washington Attell (1884-1970) grew up on the streets of San Francisco relying on his fists to punish the bullies foolish enough to come after him. He gained national renown by taking the featherweight title in 1901. He regained the belt in ‘06, going on to defend 18 times. He became a popular Manhattan store owner before taking his Little Champ act to vaudeville while continuing to box occasionally until 1917.

Attell became notorious for his alleged involvement with “The Big Bankroll” Arnold Rothstein. He was reputed to be A.R.’s sometime bodyguard. Whatever friendship Abe may have had for the greatest crime lord of his day, Rothstein did not reciprocate, as indicated by his testimony in the Black Sox prosecution: “The whole thing started when Attell and some other cheap gamblers decided to frame the Series and make a killing. The world knows I was asked in on the deal and my friends know how I turned it down flat. I don’t doubt that Attell used my name to put it over. That’s been done by smarter men than Abe. But I was not in on it, would not have gone into it under any circumstances and did not bet a cent on the Series after I found out what was underway.”

Many who have tried to unravel the sordid affair assert that Attell and another gambler, Sport Sullivan, vied for the direct role in the fix. Rothstein, it has been reliably reported, sought to take advantage of the rivalry among leagues of gamblers to make a killing as a bettor, not, as was oft alleged, as the financial backer of the misbegotten enterprise. In any event, Abe Attell became inextricably tied to Rothstein and was one of those formally charged. He fled to Canada for a year, supposedly to avoid being deposed. Eventually he and others were prosecuted, but the case dissolved when, wonder of wonders, the whole grand jury file somehow disappeared. The fingerprints of notorious defense attorney Bill “The Big Mouthpiece” Fallon seemed to be all over the matter, perhaps explaining why he made the big bucks.

- Before his alleged involvement in the Series fix, Attell’s stellar fight career had included a first: he and brother Monte, a bantamweight, became the first brothers to hold concurrent world championships

- In 172 professional fights, Attell lost just 9 of them. He won 125, 51 by KO, and had 21 draws and 8 no contests.

- Despite the stain of scandal, Abe lived a long and colorful life and was honored with numerous inductions into boxing halls-of-fame, including the Boxing Hall of Fame in 1955, the National Jewish Sports Hall of Fame in ‘82 and the San Francisco Boxing Hall of Fame in ‘85

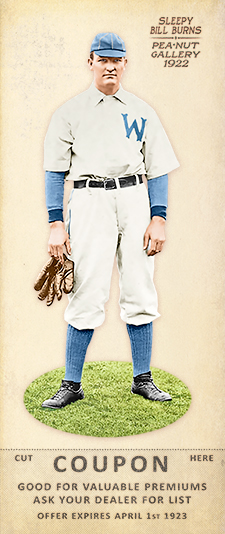

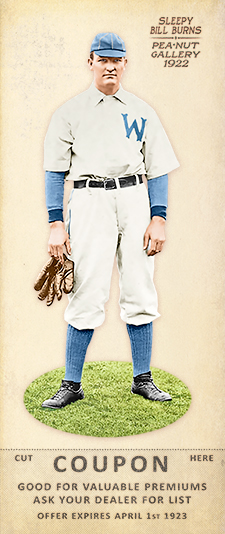

- Series: 1919 Black Sox Scandal

- City: Washington, D.C.

- Team: Senators

- League: American League

William Thomas Burns (1880-1953) was an American League pitcher who didn’t finish well. He began his career of failed finales in his rookie season, 1908, with the Washington Senators. Bill took a no-hitter into the ninth inning and got two more outs before Germany Schaefer spoiled his bid and won the game. A year later with the White Sox, and facing his former teammate Walter Johnson, Burns lost another no-hitter with one out to go. Not until Dave Stieb had the misfortune of losing (consecutive!) two-out no-nos in 1988 would such a fate befall another major leaguer. The ‘08 season was a fine one for Bill, who apparently didn’t earn his “Sleepy” sobriquet until later, when he developed a reputation for a lackadaisical demeanor on the mound. He had an outstanding 1.69 ERA in 1908, but would never win more than eight games in a season en route to a 30-52 career record.

It was his career-ending tour with the Tigers in 1912 that would prove fateful for Sleepy Bill. On May 18, teammate Ty Cobb couldn’t resist battering a maimed and abusive fan, earning a suspension from league president Ban Johnson and triggering a walk-out by the team. Detroit’s owner wanted to forfeit and Johnson threatened to fine him if he didn’t field a team in Philadelphia. Thus Burns crossed paths with Billy Maharg, who was one of the replacement players against the Athletics. Years later, the two would team up in a scheme that provided the most notorious of endings for Bill Burns: the end of any reputation for honor in baseball. He and ex-boxer, and shadowy operator Maharg, likely at the behest of the most famed gambler of his day, Arnold Rothstein, would fix the 1919 World Series. Burns met with Eddie Cicotte and Chick Gandil at a New York hotel prior to the postseason. Investigation later revealed that Burns acted with Rothstein’s chauffeur, Maharg, and claimed to be representing someone known as “A.R.” For all of the rumors and speculation surrounding the Black Sox scandal, one bit of testimony was clear. Burns told the Assistant State Attorney: “I had the hundred thousand dollars to handle the throwing of the World Series. I also told them that I had the names of the men who were going to finance it.”

- Sleepy Bill, known for carelessness as a pitcher, was a willing henchman to the biggest crime lord of the era. He displayed a carelessness for the truth, for morality and integrity, forever staining America’s Pastime

- Another footnote to the Black Sox: Jean Dubuc was a player on the 1919 New York Giants (and had also been on the 1912 Tigers). Despite having an excellent year for the Giants in 1919, John McGraw released Dubuc, unexpectedly and without explanation, before the 1920 season. Dubuc then left the country to play and, in retrospect, lay low in Canada for 1921, and returned to play minor league ball in the States in 1922, but would never again play in the major leagues. When asked later why he had released Dubuc, McGraw stated that Dubuc "constantly associated" with Sleepy Burns and suspected that the two of them, along with Hal Chase, had conspired to ensure the Giants would lose out to the Reds during the 1919 pennant chase. Further raising suspicions of Dubuc's complicity in the year-end gambling scandals of 1919, his former Giants teammate Rube Benton testified in court during the Black Sox hearings that Dubuc had been tipped to the world series' fix by an anonymous telegram that urged him to place bets on the Reds. Combining that testimony with McGraw's suspicions, many (including The Sporting News) considered Dubuc's "guilty knowledge" of the fix as evidence of conspiracy equal to that of some other scandal participants, such as Buck Weaver and Joe Jackson, but Jean Dubuc somehow escaped such judgement from Kenesaw Mountain Landis and was never formally banned from professional baseball. Dubuc would hence go on to have a successful career as a scout for the Detroit Tigers, signing Birdie Tebbetts and Hank Greenberg. Nobody knows who sent Dubuc that anonymous telegram in 1919, but the most common candidate proposed by historians is Sleepy Bill Burns.

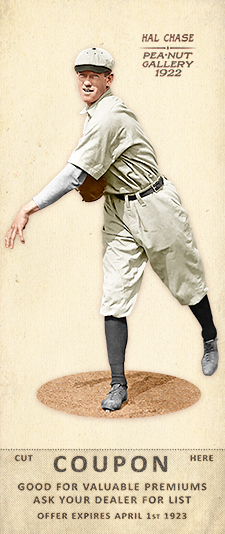

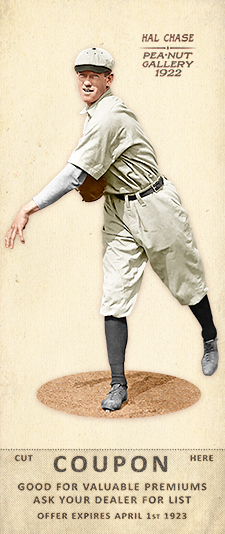

- Series: 1919 Black Sox Scandal

- City: New York

- Team: Highlanders

- League: American League

Harold Homer Chase (1883-1947) may have been among the best first-basemen ever, but his “errors” place him as mediocre at best. His own words are his epitaph: “I am an outcast, and I haven’t a good name. I’m the loser, just like all gamblers are.” A star for the NY Highlanders for the first nine years of the franchise, admired by peers such as Babe Ruth and Walter Johnson, Chase even went on to out-poll dozens of later entrants into the Hall of Fame. Such was his prowess at first and plate. But his compulsion to wager, and the ease of access to illicit betting (the bookies were in the front row) consigned this great player to ignominy.

- Chase’s spiral from NY idol to deportee from Mexico evidenced his inability to stay straight in an era when the crooked path was wide and inviting

- Chase was banned from baseball for life by commissioner Kennesaw Mountain Landis in 1922 for his (unsubstantiated) role in the 1919 Black Sox scandal

- Despite the controversy that consumed his career, Chase received more HOF votes in 1936 than 18 future HOFers, and more votes in 1937 than 32 future HOFers, but he never appeared on the ballot again

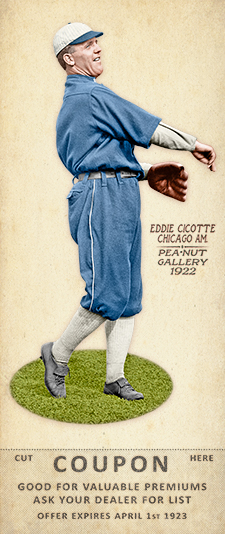

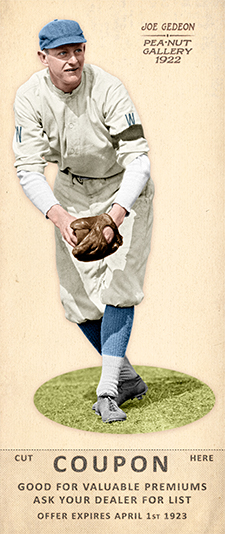

- Series: 1919 Black Sox Scandal

- City: Chicago

- Team: White Sox

- League: American League

Edward Victor “Knuckles” Cicotte (1884-1969) won 208 games and a World Series with the White Sox in 1917. The Sporting News said in 1918 that “Perhaps no pitcher in the world has such a varied assortment of wares….” But it was Eddie’s first pitch of the 1919 Series that plunked Morrie Rath in the back and signaled the fix was in. No one was ever convicted of the infamous Black Sox scandal but Cicotte, with seven teammates, never played ML ball after his tearful confession following the ’20 season.

- Cicotte, Shoeless Joe, and other banned Sox players went on to barnstorm under false names

- His mastery of the knuckleball led to a transformation of his career. His control improved to the point of walking only 89 in 572 innings in 1918/19 combined.

- Series: 1919 Black Sox Scandal

- City: Chicago

- Team: White Sox

- League: American League

Oscar Emil Felsch (1891-1964) was a sunny-tempered soul, the epitome of the hail-fellow-well-met. Born into the German community of Milwaukee, Felsch excelled at baseball and went on to become the star center fielder for the Chicago White Sox for six seasons spanning the most tumultuous era in franchise and baseball history. Charles Comiskey brought Hap to the Windy City in 1915 as part of one of the most successful rebuilding efforts in the game’s history. Felsch joined future Hall of Famer Eddie Collins and the incomparable “Shoeless” Joe Jackson, forming a club that would become a dominant force in the American League through the WWI years. Indeed, he forged the kind of career that Jim Nitz of SABR states might have been remembered “as one of the best all-around center fielders in baseball history.” He led his hard-hitting team in home runs and slugging, he was a league-leader in both offensive and defensive stats. And everybody loved Hap.

Years after the sordid story of the Black Sox had waned, Felsch, amiable as ever, was virtually the sole source for writer Eliot Asinof’s Eight Men Out. Hap was as humble as he was forthright in recounting his role in the scandal that shook baseball and ushered in the Judge Landis autocracy that forever changed the structure of the game. “I shoulda knew better,” moaned the aged and infirm former slugger. Earlier he had testified to foreknowledge and acquiescence to the gamblers’ schemes, but always denied actively trying to lose a game, much less the Series.

Despite his reputation for a very sociable demeanor, Felsch suffered under the indignities inflicted by miserly Comiskey. Injuries, his brother’s war wounds, his father’s illness, all took a toll as well in 1919, as did the clubhouse friction between players riven by the war effort. Felsch, Jackson and others had taken defense-industry jobs in ‘18 while others had enlisted. Rivalries erupted and friendships were damaged. Into the tensions stepped unctuous underworld minions of east coast mobsters. The resulting scandal enmeshed Felsch and he never pretended innocence.

- After being ousted from organized ball by Landis, Felsch endured years of litigation mingled with varying efforts to play ball. Eventually he went north and enjoyed success in Canadian circuits while always maintaining the love and support of his hometown

- Series: 1919 Black Sox Scandal

- Hall: J.G. Taylor Spink Award Recipient

Hugh Stuart Fullerton III (1873-1945) was one of the most respected sports journalists of the early twentieth century, introducing colloquial language and a human interest slant to the field. He was a mentor to at least two other all-time great sports scribes: Ring Lardner and Grantland Rice. He established his keen analysis of baseball stats early on when he projected one of the greatest World Series upsets, calling the 1906 tourney for the woeful-hitting White Sox over the 116-game winning Cubs in a crosstown rivalry for the ages. Yet, it wasn’t Fullerton’s on-field acumen that indelibly stamped his legacy on the game. The character-trait that shone most clearly was his integrity and zeal for the honor of the national pastime when, in 1919, Hugh refused to do what most in and outside the game did that year: duck and cover.

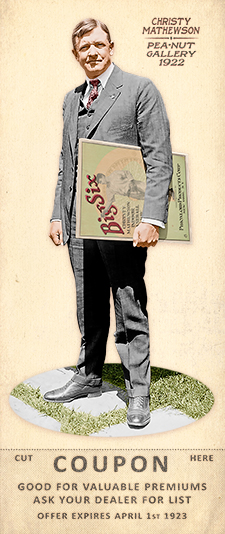

In blowing the whistle on what came to be known as the Black Sox scandal, Fullerton, aided by his ally Christy Mathewson, used his articles in the Chicago Herald-Examiner as a claxon, forcing the nation to face the existential threat posed by the vast network of underworld gamblers preying on players and the game itself. It took a year before his and Matty’s efforts bore fruit but, eventually, despite a widespread conspiracy of silence, charges were filed and eleven players were banned from baseball for life. No one was ever convicted of a crime, largely due to evidence that vanished quicker than a magician’s coin. Hugh was credited with shining the purifying light of investigative journalism at its finest on the threat. Baseball historian David Q. Voigt said, “In 1919 it was Fullerton’s detective work that unraveled the web of fact and rumor and exposed the crooked work of the Black Sox.” In a 1932 retrospective, Westbrook Pegler commented on the uniqueness of Fullerton’s contribution: “The fake world series of 1919 produced some of the worst newspaper reporting that the American press ever has been guilty of, and while all of us who were detailed to cover the show were not fired for missing the greatest sport story in 20 years is something that I have never understood. We were terrible.”

- Mathewson had covered the Series for a New York paper. He became Fullerton’s “expert witness,” parsing each key play for signs of wrongdoing

- Fullerton was a founder of the Baseball Writers Association of America. He is credited as the first of his field to include direct quotes of players in his coverage of the sport

- Elected to the Hall of Fame for Sportswriters via his selection for the J.G. Taylor Spink Award in 1946

- Series: 1919 Black Sox Scandal

- City: Chicago

- Team: White Sox

- League: American League

Charles Arnold Gandil (1888-1970) was described in the Chicago Tribune in March 1917 as “the ideal type of athlete – a fighter on the field, a player who never quits under the most discouraging circumstances and … is one of the most dangerous batters in the league when a hit means a ball game.” This tribute heralded Gandil’s return to his original club, Charles Comiskey’s White Sox. He didn’t set the world on fire in ’17 and ’18 but the club became a strong favorite to win it all in 1919. Rife with dissension directed at the miserly owner, by his own admission in a 1956 SI account, Gandil led a conspiracy to throw the Series. Everything came undone and by 1921 eight Sox players were banned for life. Gandil admitted to being the main instigator of the affair but insisted the actual Series losses were unintentional.

- Was a stand-out first-baseman for Clark Griffith’s Senators

- Lifetime BA of .277

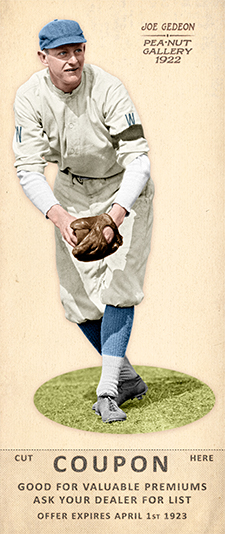

- Series: 1919 Black Sox Scandal

- City: Washington, D.C.

- Team: Senators

- League: American League

Elmer Joseph Gedeon (1893-1941) became an unwelcome footnote to the most notorious scandal in baseball history. Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis had permanently banned eight White Sox players in the aftermath of the 1919 World Series affair. A few months later, Landis ousted young Joe, a slick-fielding second-baseman for the St. Louis Browns. The bad boy from the PCL, who had defied Clark Griffith over his rookie assignment, had refused to get off a train in a snowstorm, and had dismissed the stately Charlottesville hometown of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison as “a rotten little mud town down in Virginia,” ended up as the “ninth man out.” Landis found Gedeon had “guilty knowledge” of the conspiracy to fix the Series. Thus ended the rising career of one of the best defensive players at his position and a canny batter, especially skilled in the hit and run.

- Gedeon played for the Senators, Yankees and Browns. His friendship with one too many White Sox players and way too many St. Louis gamblers put him in harm’s way

- Became the first of the banished players to die, at age 47, back home in California

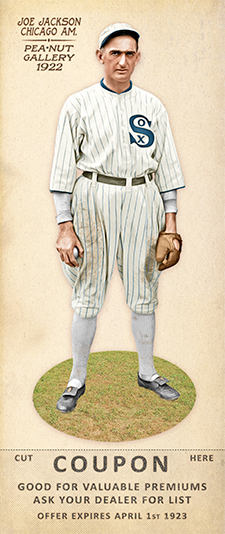

- Series: 1919 Black Sox Scandal

- City: Chicago

- Team: White Sox

- League: American League

Joseph Jefferson Wofford Jackson (1887-1951) had the “perfectest” swing according to Babe Ruth who copied it. After nearly a century of more contenders, many would still say Shoeless Joe was the purest hitter ever to wield a baseball bat. Expelled from baseball by Judge Landis, Jackson lives in infamy despite demonstrating prowess at the plate and grace afield. While he will ever be branded with the “Black Sox,” Jackson stirred passions that still echo in baseball today.

- Still ranks as the third-highest career batting average in history (.356)

- His .408 average in 1911, his rookie season, is sixth-highest in the modern era

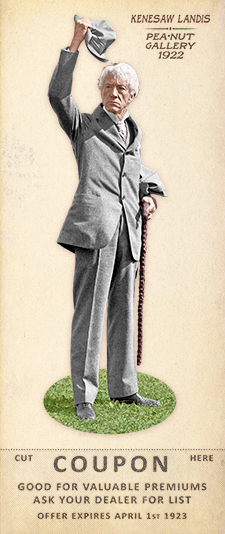

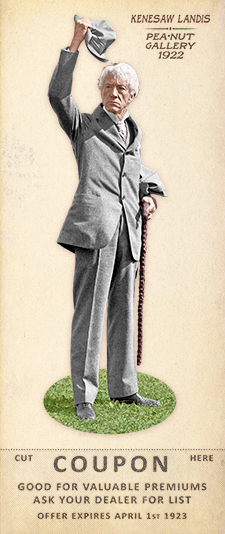

- Series: 1919 Black Sox Scandal

- Hall: National Baseball Hall of Fame

Kenesaw Mountain Landis (1866-1944) grew up in an era when a man could become a lawyer before going to law school; go to school later, turn down an ambassadorship, and be appointed to the Federal bench by Teddy Roosevelt all before the age of 40. He would soon vindicate TR’s eye for legal talent by hitting Standard Oil with a huge judgment in the “trust-busting” era. The young jurist thus displayed a boldness to tackle the biggest of business interests in a day when big business was a colossus bestriding America. Small wonder then, that in 1920, when major league owners recognized that their sport had a problem, they looked to Judge Landis to solve it for them.

Landis, named for the Civil War battle where his Ohio father was wounded, would live up to his name as a man who would make a massive impact on America’s Pastime and, since baseball “was America” as so many pundits often said, upon the nation itself. It wasn’t just Landis’ early political and legal accomplishments that foreshadowed his later role as baseball’s first commissioner. As District Judge in Chicago, KML cut a striking figure: “The Judge was always headline news. He was a great showman, theatrical in appearance, with his sharp jaw and shock of white hair, and people always crowded into his courtroom, knowing there would be something going on. There were few dull moments,” per friend and journalist A.L. Sloan.

Landis, a lifelong fan, and ardent White Sox supporter, heard a case brought in the Federal League uprising in which many baseball insiders feared he would rule against the reserve clause. He held hearings in January 1915, but never issued a ruling. KML outlasted the parties who eventually settled the case with reserve clause intact. Nevertheless, Landis was destined for far greater involvement with the game. Gambling and bribery of players had been an open secret for many years and reached a crisis in 1920 in the aftermath of the Runyanesque comedy of errors known as the Black Sox Scandal.

Baseball was ruled then by the “National Commission,” a triumvirate of both league presidents and Reds owner Garry Herrmann. Herrmann stepped aside, leaving a deadlock, and into that void stepped Kenesaw Mountain Landis. “We want a chairman who will rule with an iron hand…” said NL president John Heydler. (Translation: Please save us from ourselves.) The owners went hat in hand to KML’s courtroom and waited for him to finish his docket. They pitched and he caught, accepting the job of first Baseball Commissioner.

- Landis was an immediate hit with the public when he stepped into a seven-year term while continuing his day job

- “If I catch any crook in baseball, the rest of his life is going to be a pretty hot one” was KML’s vow and he made good, ousting the eight accused White Sox for life despite their acquittal in court. He forced owners to divorce themselves from horse racing and cracked down on all instances of gambling that he encountered, true to his word

- Elected to Hall of Fame: 1944

- Series: 1919 Black Sox Scandal

- Hall: National Baseball Hall of Fame

Christopher Mathewson (1880-1925) was the consummate right hander of the early 20th Century. His “fadeaway” pitch baffled NL hitters from 1900-16. Mathewson won 22+ 12 straight years, 30+ 4x, and holds the modern NL record with his 37 wins in 1908. He hurled 3 shut-outs in 6 days to gain his sole world championship in 1905.

- One of the “first five” into Cooperstown

- Accomplished all this while honoring his Christian faith by not pitching on Sundays

- This Pilgrims card duplicates and preserves the uncorrected spelling error on Mathewson's original T201 Mecca card

- Elected to Hall of Fame: 1936

- Series: 1919 Black Sox Scandal

- City: Chicago

- Team: White Sox

- League: American League

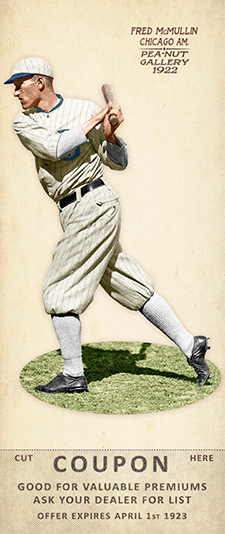

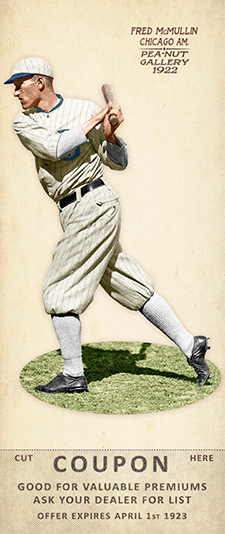

Fred Drury McMullin (1891-1952) has been called the “forgotten man” of the Black Sox. Writing for SABR, Jacob Pomrenke called McMullin the "Eighth Man Out, the most obscure of the White Sox players who agreed to throw the 1919 World Series to the Cincinnati Reds."

As a nondescript utility man with little promise to impact the series, Fred would certainly seem to be the unlikeliest member of that talented team to be pursued and paid off by gamblers. Some have suggested that, as the team’s scout, Fred may have contributed to the scheme by providing misleading information to his teammates about Reds hitters and pitchers. Or perhaps, as it is most commonly suggested, McMullin implicated himself in the scandal when he allegedly overheard talk of throwing the Series and insisted on his inclusion in the conspiracy. And yet Ed Cicotte testified that "the idea of the fix had originated in a conversation with Gandil and McMullin." Like so many mysteries that will forever envelope the 1919 Black Sox, the truth of how and why Fred McMullin was involved in the scandal may never be known.

McMullin had come out of West Coast ball where he impressed the Tigers enough to give him an audition at the end of the 1914 season. Fred languished on the bench, watching the likes of Cobb and Crawford before getting his only appearance that year in Fenway, mopping up a Red Sox laugher and striking out in his only at-bat. Returning to California allowed Fred to build his resume and the White Sox signed him for the ‘16 campaign. Again, he joined a stacked team with little chance of breaking into the lineup. In 1917, McMullin got into late-season games and did well; especially helping with his defense in the Series against the Giants, which the Sox won. Fred used his $3,600 bonus to buy a small house.

Following the war-shortened ‘18 season, the White Sox were again a dominant force in 1919. Owners feared the year would be a loss in the war’s aftermath and scheduled another truncated schedule which included smaller player paychecks. In the lead-up to the postseason, Chick Gandil seems to have led the conspiracy that would ensnare Fred and six more teammates.

- McMullin stayed mum the rest of his life concerning the fix

- Unlike his teammates, Fred didn’t try to barnstorm, but he did play some semi-pro ball in LA - until Irish Meusel was fined $100 by the Phillies for playing against him

- McMullin ended his working life in law enforcement, as a court marshal in Los Angeles, and died on the job from a stroke

- Series: 1919 Black Sox Scandal

- City: Chicago

- Team: White Sox

- League: American League

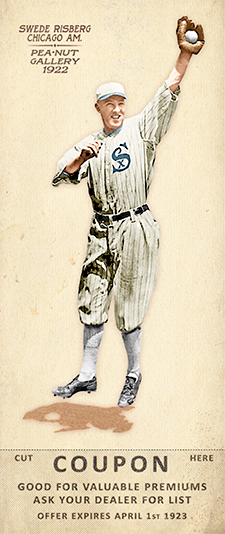

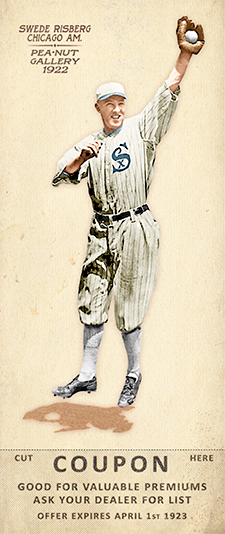

Charles August Risberg (1894-1975) grew up on the streets of San Francisco, dropping out of school in the third grade. He had a flair for baseball and, when he switched to shortstop, he blossomed into a defensive star worthy of a call-up to the White Sox in 1917. Swede’s minor league experience foreshadowed the future outlaw character he would display almost from his arrival in the big leagues. In 1913, when Risberg traveled to the LA area to play in the Pacific Coast League, he was drawn to the Vernon/Venice Tigers. At that time these were the only communities in Los Angeles county that were “wet.” Booze was the defining identifier for owner Pete Maier’s club. When it was in Vernon fans could enter the park directly from Doyle’s bar.

Risberg made the big club based on his defense, but hit so poorly in his rookie season that he only got two pinch hitting appearances in the ‘17 Series when the Sox beat the Giants. Swede returned to California for part of the 1918 season, escaping the draft by taking a shipyard job that amounted mostly to playing semi-pro ball for the company during that “work or fight” year. By his own testimony, Swede was crooked throughout his major league tenure, all with Chicago. He claimed to have been the organizer of a scheme in 1917 to bribe Tiger players to throw some games. And he was at the center of the Black Sox Scandal in 1919. Later many would assert that, despite the clear conspiracy with gamblers, the Reds won fair and square although they were thought to be far inferior to Chicago. It is difficult to make a case from the players’ performance. Risberg would be an exception. He apparently threw himself into the fix with zeal, committing a record eight errors and going 2 for 25 at bat. And his reported payout of $15,000, which was more than four times his salary, was a far bigger reward than others realized. He may have earned his bonus because he served as an enforcer. Joe Jackson received a death threat from Risberg if he “blabbed.” Shoeless Joe would later describe Swede as a “hard guy.”

- True to his scofflaw nature, Risberg defied Judge Landis’ ban and played exhibition ball for years. As the youngest of the “Eight Men Out,” and having a very brief tour in the majors, he had incentive to play wherever he could

- It may be that the game he tarnished got its revenge. Swede had been spiked in Chicago and the wound never properly healed. He lost the leg in his old age, dying in a nursing home in Redding, CA on his 81st birthday

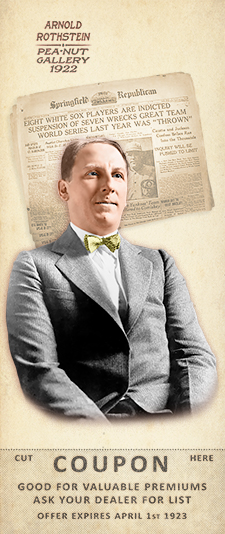

- Series: 1919 Black Sox Scandal

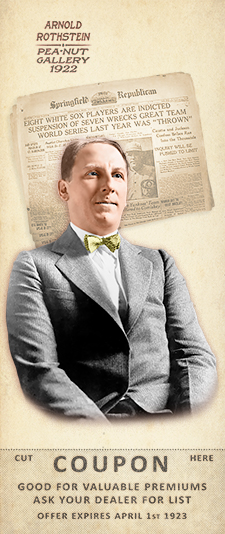

Arnold Rothstein (1882-1928) has been described by historian Leo Katcher as “the J.P.Morgan of the underworld; its banker and master of strategy.” Born into a wealthy New York Jewish family, Rothstein would use his vaunted intelligence to rise to the top of criminal enterprises. Nicknamed the Brain, the Fixer or the Big Bankroll, he was most often known to his underlings as A.R.; and underlings he had. Rothstein was mentor and boss to some of the most notorious gangsters of the 20th century: Meyer Lansky, Legs Diamond, Dutch Schultz, Frank Costello and Lucky Luciano, who said of A.R., “He taught me how to dress...how to use knives and forks and things like that at the dinner table, about holdin’ a door open for a girl. If Arnold had lived a little longer, he could’ve made me pretty elegant.”

Rothstein is credited with making crime a business, using his acumen to organize a network of illicit operations, the godfather before there was a Sicilian Godfather. Per Lansky, “Rothstein had the most remarkable brain. He understood business instinctively and I’m sure that if he had been a legitimate financier he would have been just as rich as he became with his gambling and the other rackets he ran.” His instincts proved very acute when his bodyguard Abe Attell brought him Chick Gandil’s plot to fix the 1919 World Series. Rothstein is said to have rejected the scheme, accurately assessing the harebrained crew of conspirators. After learning that other groups of gamblers were getting involved, some say he fronted $80,000 and then won a fortune betting on the White Sox to lose.

Those bets presaged later huge takes at the track and poker tables that made A.R. the most famous criminal of an increasingly lawless era. The year after the Series fix, Rothstein found the greatest opening a crime lord ever had as Prohibition began. He made massive profits, but got out of the traffic early as he realized he couldn’t control the liquor business to his liking. He was all about control, once remarking that he would bet on anything but the weather because “I can’t fix the weather.”

- As with all of the players and gamblers directly implicated in the Black Sox scandal, Rothstein escaped legal consequences. He testified that he had been asked to participate, but always denied a role

- Slain by a card player who said A.R. had stiffed him on a $300,000 marker, Rothstein took a day to die, taking his killer’s identity to the grave. In a gesture to honor Arnold's upright father, his funeral was officiated by New York’s most prominent Orthodox rabbi

- Series: 1919 Black Sox Scandal

- City: Chicago

- Team: White Sox

- League: American League

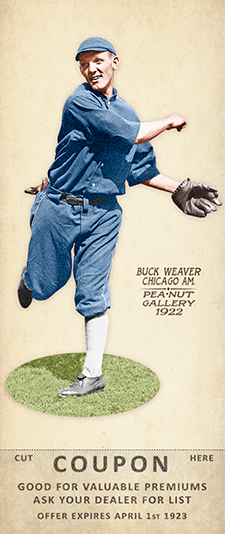

George Daniel Weaver (1890-1956) climbed to a lofty height during his baseball career and plummeted to an historic low that would test any man. Buck’s dad insisted he forego his mother’s funeral to begin his pro career in the White Sox system. He ended his career when Judge Landis banished him from the game along with 7 fellow Sox. In between, this gregarious, cheerful soul basked in the shadows of the Great Pyramid sporting a fez during the 1913 world tour and danced for joy after Comiskey’s club locked up the ’17 Series, a team he had led in batting and afield. Although pilloried with his teammates for throwing the 1919 Series, Weaver played errorless ball, hit .324, and was never accused of taking money. He would spend the rest of his life trying to clear his name. After Cicotte and Jackson confessed, the Sporting News headlined: “Chicago Fans Grieve Most for Weaver and Still Hope for Him.”

- Played exclusively for the White Sox (1912-1920), averaging .272, and was the only banned player to remain in Chicago

- Buck successfully sued his penurious owner for his 1921 salary

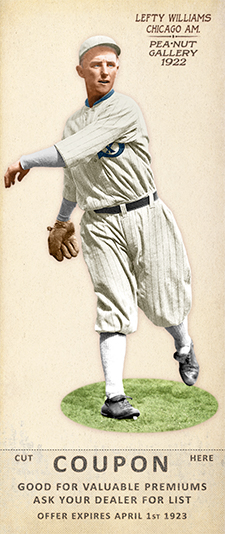

- Series: 1919 Black Sox Scandal

- City: Chicago

- Team: White Sox

- League: American League

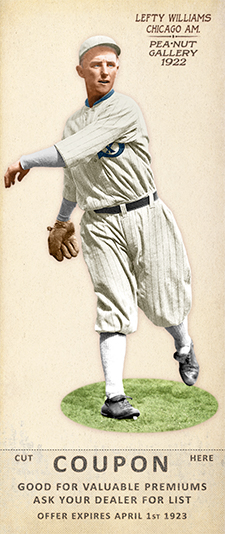

Claude Preston Williams (1893-1959) was the third Black Sox player to confess and the first to hear the jury say “Not Guilty,” sparing him from prison but dooming him to a life of shame. Lefty was being groomed to become the White Sox ace and had consistently challenged Cicotte for that unofficial designation throughout the fateful 1919 season. But teammate Chick Gandil’s blandishments lured Williams into the scandal that would forever taint the talented Chicago squad. By the time the Pale Hose finally won another pennant in 1959, Lefty was a month from death. The press noted that he was unable to celebrate, being “tired and aging and ill and sick at heart.” On pace to be an elite southpaw of the 1920s, Lefty Williams instead became a man broken by his betrayal of the game at which he excelled.

Lefty had come up with the Tigers as a kid in 1913, but floundered and was sent to the Pacific Coast League. He starred for the Salt Lake City Bees in ‘15, earning a trip back to the majors when Charles Comiskey purchased his contract. Williams validated the owners’ judgment by helping lead the team to the 1917 pennant with a 17-8 record. The following year was a lost cause for MLB with the war on and the government calling up players. Many, including Williams and his pal Joe Jackson, sought shipyard jobs to escape the draft. This became a wedge within teams and perhaps none more than the Sox. Labeled as “unpatriotic,” the “work or fight” players who chose defense jobs were vilified by management and teammates alike.

Nevertheless, in 1919 Comiskey welcomed his charges back to the fold. Williams was stung by the owner’s stiffing him of his final ‘18 paycheck, adding to an aggrieved mindset. Gandil found an all-too-willing mark when he peddled his scheme to throw the Series that everyone knew the White Sox would be in. Overcoming wildness that plagued his early years, Lefty was terrific that year with a 23-11 record and 2.64 ERA. His remarkable control made his World Series performance all the more notorious. He logged a record three losses and curried trouble every start with a rash of bases on balls. The only other pitcher to lose three games in a Series is George Frazier of the Yankees, who equaled Lefty’s dubious feat in 1981.

- Williams expressed remorse even before the Series ended. Some believe he was threatened by mobsters. Having already received $5,000 mid-Series, he later admitted “I was sorry. I wanted to be out of it and not mixed up in it at all.”