“The first thing I look for in the Sunday papers is who is below the Gerhardt line.” — George Brett

Okay, Brett didn’t really say that. It’s likely that George Brett has never heard of Joe Gerhardt, never knew how the second sacker’s anemic batting totals on occasion could make Mario Mendoza appear to be as accomplished a hitter as . . . well, George Brett.

Brett was of course referring to Mendoza, a light-hitting middle infielder whose Seattle Mariners’ teammates Tom Paciorek and Bruce Bochte had originated that batting demarcation, as the level below which no self-respecting batsman would want to fall. Mendoza was a career .215 hitter, but in 1979, his first year with the Mariners, he played in 148 games and hit .198, suggesting that the true focus of the Mendoza Line was in separating those who batted .200 or higher, and those who hit less.

But Mendoza had nothing on Joe Gerhardt.

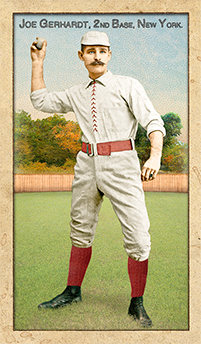

Even in a gloveless era when a middle infielder’s lack of clout was glossed over if he could catch the ball, Gerhardt was a cut above . . . or a cut below, depending on your point of view. He was seemingly the man they had in mind when, years later, the phrase “Good field, no hit” came into vogue.

But as is often the case with players whose careers are reduced to a single meme, Gerhardt’s story is a lot more interesting the more you know. He actually had a better career average than Mendoza, .227-.215, but he mixed some significant highs with some historic lows. A player like Gerhardt is often seen as getting by on his glove (all the more remarkable in the days before fielders wore gloves), but his 21-year professional career likely was predicated on more than just some fancy fielding.

—————————————————

John Joseph Gerhardt was a first-generation American, born on Feb. 14, 1855 in Washington D.C. to Prussian and German immigrant parents. His father served as a general in the Union Army during the Civil War, and Joe grew up playing the budding National Pastime in the national’s capital. He got his professional start locally, playing a handful of games for the Washington club in the National Association in 1873 and a handful more for Baltimore in 1874, before joining the New York Mutuals as their regular third baseman the following season.

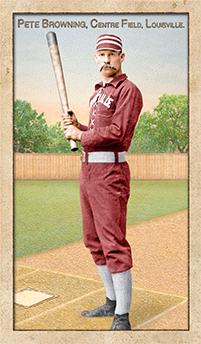

Gerhardt was there at the beginning of the National League in 1876 and, for a few seasons, appeared to be a star on the rise. He played for Louisville in the NL’s inaugural season, as the Grays’ first basemen, batting a solid .260 with 15 extra-base hits in 65 games. The following season, he moved to second base full time, leading the league in chances per game and finishing second in fielding percentage. He hit .304, the second best average on the Grays, while driving in a team-high 35 runs. As a 22-year-old, he was on the top of his game.

And he couldn’t have found himself in a worse place in the baseball world.

Louisville contended with Boston for the title for much of the year, until a late-season swoon that sent up red flags around the league. An investigation led to the discovery of key players on the Grays being paid to throw the pennant, and eventually star pitcher Jim Devlin and George Hall, Louisville’s top hitter, confessed to being part of the scheme. They were banned from the league for life, along with Bill Craver, a veteran “hard man” who proclaimed his innocence, but played most of his career under the cloud of suspicion of dumping games; and Al Nichols, the substitute who had been the go-between with the gamblers backing the plan. Decimated, the Louisville team dropped out of the league.

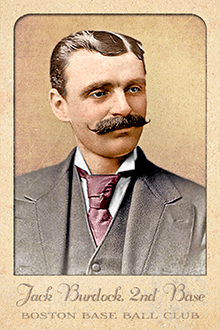

Gerhardt had no trouble catching on with another team, signing with Cincinnati. In 1878, he joined a lineup that included future Hall-of-Famers Mike “King” Kelly and Deacon White, slugger Charley Jones and hard-hitting Cal McVey, who nine years earlier had been a youngster on the unbeaten Cincinnati Red Stockings, baseball’s first professional team. With Gerhardt batting .297 and ranking second in fielding only to Boston’s Jack Burdock among National League second basemen, the Reds made a run at the pennant, only losing by four games to Boston’s Red Caps.

But suddenly, Joe Gerhardt’s ability to hit deserted him. It’s impossible to tell why; the official rules were tinkered with almost every year during those early seasons, but no major changes were made in the offseason of 1878-79. What we know for sure is that Gerhardt’s average dropped 99 points in one year, to .198, with only 22 runs scored in 79 games.

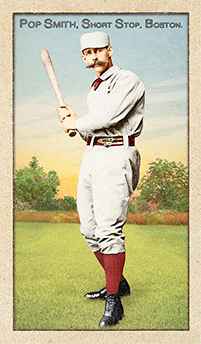

It perhaps wasn’t difficult for the Reds to cut loose their light-hitting second baseman as the scapegoat, but it turned out to be another instance of Gerhardt escaping a sinking ship. Kelly left for Chicago, McVey retired at the end of the season, White was a holdout and missed the first half of the 1880 season, and Pop Smith, hired to replace Gerhardt at second, batted an anemic .207. The Reds finished dead last, and in an attempt to make some extra money, they rented out their park to local semipro teams on Sundays and permitted them to sell beer, both against National League rules. In the offseason, the Reds were booted out of the league, and the National League wouldn’t have a representative from the Queen City for another 12 years.

Gerhardt, on the other hand, simply went home. In 1880, he played for the Nationals of Washington in the National Association. But this was not the National Association of a few years earlier, baseball’s first legitimate major league. This was a four-team independent East Coast league. It’s one claim to fame is that Washington, after winning the league title, bested the NL champion Chicago White Stockings in a best-of-seven postseason series, the details of which appear to have been lost to time. Even against lesser competition, Gerhardt could only manage a .204 batting average.

Detroit, which had been awarded Cincinnati’s spot in the National League, signed Gerhardt for the 1881 season. He played well in the field, batted a reasonable .242 and the Wolverines finished a surprising fourth in the standings. But the American Association began play the following year, and Gerhardt apparently wanted to relive his glory days in Louisville, with the new AA franchise. When Detroit turned down his request for a release, he chose instead to sit out the season. Given that the National League owners were exerting more and more control over the players, this may not have been the best move, as he was blacklisted by the league.

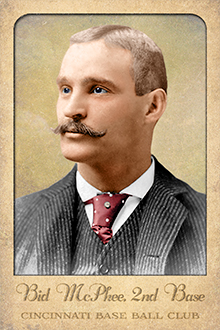

Gerhardt finally made it to Louisville in 1883, and was named player-manager. He inserted himself in the clean-up spot in the lineup, but eventually dropped himself to ninth, proving at least that over the season he had developed keener skills for evaluating batting talent. He led American Association second basemen in fielding range and was second in fielding percentage to Bid McPhee while batting .263, but missed several weeks of the season after getting hit in the face with a pitch. The following season was marred by the illness and death of an infant child, and Gerhardt was replaced as manager in mid-season. His batting average fell to .220.

But in those times of changing labor situations in baseball, Gerhardt was learning how to play the game. He signed for both of his seasons in Louisville with the stipulation that he not be reserved after the season and he took the opportunity to sign with the New York Giants for 1885 at a hefty pay raise. And if Joe Gerhardt hadn’t yet risen to the roll of the poster child for the weak-hitting, good-fielding infielder, that would soon change dramatically.

—————————————————

The 1885 team that Gerhardt joined was quite different than the Giants of ’84 who’d finished in fourth place. This was partly because of new acquisitions, and partly because of new deployments for old stars.

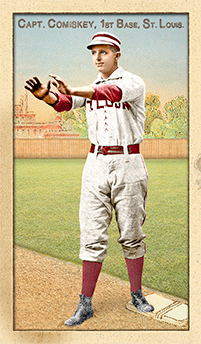

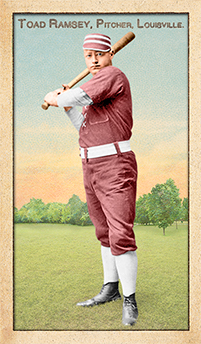

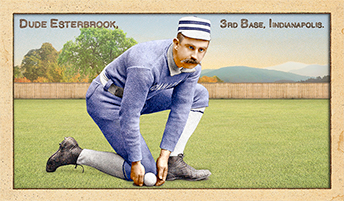

The former resulted from a bit of skullduggery by John Day, president of the Metropolitan Exhibition Company, which owned both the National League’s Giants (then still known as the Gothams) and the New York Mets of the American Association. The Mets were the defending AA champs, having lost to Old Hoss Radbourn and the Providence Grays in the World Series of the previous fall. But admission in the AA was 25 cents per fan, as opposed to 50 cents in the NL; therefore, a National League powerhouse was of more value to Day than an American Association champion. The Mets released standout pitcher Tim Keefe and hard-hitting Dude Esterbrook, and after the mandated 10-day waiting period, the pair was signed by the Giants.

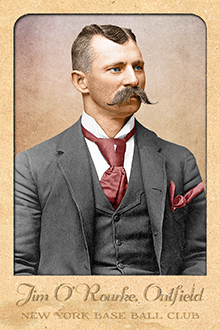

Meanwhile, Jim O’Rourke, another future Hall-of-Famer who had been the face of the Buffalo franchise for four seasons as its player-manager and top hitter, was in the market for a new team. O’Rourke had played in Buffalo with the understanding that he would not be reserved from season to season, and when his young daughter died suddenly of an illness in the fall of ’83, he resolved to play for a team closer to his Connecticut home and told Buffalo management that 1884 would be his last year with the club. The Giants signed O’Rourke as a free agent heading into the 1885 season.

On the diamond, two future Hall-of-Famers would be getting new responsibilities. Roger Connor, who had played second base for the 1884 Giants, moved to his permanent home at first base. And John Montgomery Ward, the former pitching ace who’d played centerfield the year before, moved to the infield, at shortstop. That meant that, with Gerhardt, the Giants had all new defense up the middle.

On opening day, Joe Gerhardt was the star, singling in the eighth inning and later scoring the winning run in a 2-1 victory over Boston. It didn’t get any better than that; in fact, it got a lot worse.

The Giants had become the kind of team of which John Day had dreamed, an exciting, dominating club that would win three out of every four games. Keefe and Mickey Welch would combine to win 76 games. Four of the 10 batters in the league to hit .300 or better were in the New York lineup.

The only trouble was, Chicago was even better. The White Stockings, between John Clarkson‘s 53 victories and Cap Anson‘s league-leading 108 RBIs, held a two-game advantage in the standings when the Giants rolled into Chicago for a decisive four-game series in late September. The White Stockings won the first three games, and the pennant race was essentially over.

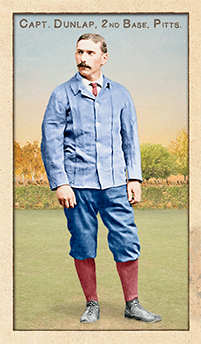

And Gerhardt? He was his usual reliable self in the field. He played every inning of every game for the Giants, an even 1,000 innings in all, was second in fielding percentage only to St. Louis’ Fred Dunlap and third in fielding range.

And he topped the league in several batting categories . . . or, rather, “bottomed” the league.

Among the 44 players with enough appearances to qualify for the batting title, he finished 44th . . . at .155.

On-base percentage? Forty-fourth, at .205.

Slugging percentage? Again, 44th at .195 . . . his 62 hits included only 14 for extra bases, with no home runs.

Gerhardt only had to look to his left to see a batter whose average was more than 200 points higher than his own. Connor led the league in hitting at .371, a full .216 higher than Gerhardt. That’s more than a full Mario Mendoza’s worth!

The Giants’ pitchers? Welch batted .206. Even Keefe, who managed just .163, would usually bat ahead of Gerhardt in the order.

The natural question is how Gerhardt managed to keep his spot in the lineup, and why the fans weren’t clamoring for his benching. But rather than being run out of town, Gerhardt was probably the most popular player on the team.

He was known as Move Up Joe, for his sideline exhortations to teammates on base to “Move up, move up.” David Nemec, in his series Major League Baseball Profiles of 19th Century players, says Gerhardt had “a gift of gab that made him enormously popular with New York fans.” Clearly, Gerhardt was the most gregarious of players on an exciting team, one who also was capable of making exciting plays in the field. In an era long before the days of the post-game interview, Gerhardt was a player to whom writers for New York’s newspapers knew they could go for a good quote. And because, in the days before national wire services, many of those writers were also correspondents for other papers around the nation, Move Up Joe became a recognized figure in the nation’s sporting press.

Maybe the best summation of all of these factors is illustrated by Gerhardt’s final day as a Giant.

With the same roster as the previous year, the 1886 Giants had another strong season, at 75-44. That was only good for third place, however, far behind Chicago and Detroit, who battled it out for the pennant into the final week of the season. Gerhardt had his usual strong season in the field and improved at the plate, but still batted a woeful .190 and was clearly the weakest link in the batting order.

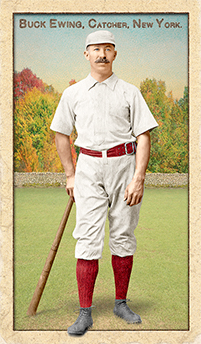

But more than that, Gerhardt’s relative popularity may have become a sore spot to some of the other players, particularly Buck Ewing, the team’s captain and catcher. Ewing was recognized as one of baseball’s greatest catchers, but was reaching an age when catching on a daily basis was taking a physical toll. So when he agreed to re-sign with the Giants for 1887, it was with the stipulation that he’d move out from behind the plate to a spot in the field . . . to second base.

A switch from catcher to second baseman (Craig Biggio to the contrary) is hardly a natural exchange, and if Ewing thought that New York’s fandom would embrace the move, he was sorely mistaken. The Giants got off to a slow start, and even when they won they weren’t particularly impressive. And the local press was quick to weigh in, singling out Ewing’s play in particular.

In the May 10 editions of the New York Times, after the Giants had fallen to Washington, 7-4, to drop to 5-4 on the season, the reporter on hand had this to say:

Ewing’s masterly inefficiency at second base was the feature of the game, and every spectator sighed because Joe Gerhardt was not there to do the work that Ewing couldn’t do. His unfitness for the position grows more and more apparent with each succeeding game, and his strength at the bat and fairly good base-running by no means counterbalances his poor play as an in-fielder.

Gerhardt, meanwhile, had only gotten into a single game, going hitless in four at-bats. And he wasn’t happy with the situation.

The following day, the baseball writer for the New York Sun had a top-of-the-page analysis of the Giants’ start, headlined Is the New York Club Petering Out? which included the following anaylsis:

Two pitchers is all they have to depend on. Danny Richardson is a very weak third base, a wooden man could play second about as well as Ewing. . . . Ewing was put on Joe Gerhardt’s post at second base for his batting, but it would be far better to have a man there who would not lose games, even if he did not win them.

But the real news of the day was to be found later in the story:

Joe Gerhardt left the Polo grounds yesterday. During the sixth inning he stepped out of the club house. He glanced around once or twice for a parting look, and hastily brushing a tear from his eye he started down the left field path toward the main entrance. As he came along with his bundle under his arm the crowd saw him. Never in the history of the Polo grounds did a player get such a reception as he received, and the cheers continued long after he was out of sight. Joe said afterward that he would get his release from the club this morning, and would at once sign with the Metropolitan Club. He will leave for Cincinnati to join that club to-morrow night.

“I was laid off because I could not bat,” said he. “The club, when they first engaged me, knew this, but they said that they did not care if I did not hit a ball once in a year. I have no hard feelings toward any of the men, but I tell you that the loss of the championship by this club for two years was caused by two men alone. No man on that team can play ball above a certain standard without getting himself in trouble, and it is this that will sooner or later break up the team. I would not play with the nine again if I never played at all.”

Pretty strong stuff . . . this again illustrates Gerhardt’s strong relationship with the media, that he would get such a complete airing of his grievances. Interestingly, the author of the piece did not expand on Gerhardt’s singling out of “two men alone.” Perhaps it was assumed that his audience would know to whom Gerhardt was referring. Perhaps it was Day and Giants’ manager Jim Mutrie being called out for mismanagement.

Or perhaps it was someone else. Consider this piece that appeared in the baseball notes of the Indianapolis News a week later:

Gerhardt is loud in his denunciation of Ewing, who practically froze him out of the New York team by signing a contract to play second and not at all behind the bat. [John Montgomery] Ward, the captain of the Giants, also receives a send-off, as he would not permit Joe to practice with the regular team. Gerhardt has joined the Metropolitans and is doing good work for them.

Whatever the case, both Gerhardt and the Giants appear to have been happy to have seen the last of each other. But Gerhardt hadn’t seen the last of New York. The Metropolitans, now no longer owned by Day, were happy to sign him. Five days later, the New York Times reported in its story of the Mets’ game against Cleveland,

Joe Gerhardt received a loud demonstration when he appear on the field.

The game was in Cleveland, an indication that “Move Up, No Hit, Good Field Joe” wasn’t just a New York phenomenon.

It would be heart-warming to report that Joe Gerhardt regained his hitting stroke, led the Mets to the American Association pennant and helped them vanquish the Giants in the World Series. This, of course, did not happen. He finished second in the league to Bid McPhee in fielding range among second basemen and batted a very Gerhardt-like .224. The Metropolitans, who were already on shaky financial grounds, finished 44-89 and folded at the end of the year.

The Giants, on the other hand, solved their problems in the infield by flipping Ewing and Richardson, the young utility player who developed into a strong second baseman. The Giants righted themselves and finished the season 68-55, well behind the champion Detroit Wolverines. But Ewing eventually realized that he could prolong his career behind the plate by occasionally taking a day off and allowing Pat Murphy or William “California” Brown to fill in, and in 1888 and ’89, he led the Giants to two National League championships and as many postseason series titles.

—————————————————

For all his popularity, Gerhardt found himself a man without a team in 1888, and spent two seasons playing for minor league teams in Jersey City and Hartford, before acting out the final scenes of his major league career.

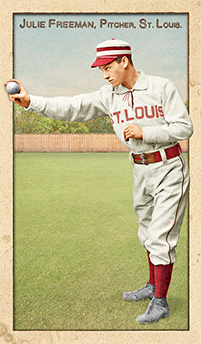

In 1890, with the National League and American Association decimated by defections to the Players League, Gerhardt caught on with the Brooklyn Gladiators, a last-minute addition to the Association. When the team folded in early August, he was taken on as the player-manager of the St. Louis Browns. He had the ultimate Joe Gerhardt season, leading the AA second baseman in every category except errors . . . all while batting .217, with career highs of three home runs and 51 RBIs.

But the Browns released him after the season. He hooked up with a Louisville franchise for a third time the following season, but lasted only two games before returning to New York to play for the Albany team in the Eastern League. After three seasons as player-manager with the Senators, he called it a career. He remained in New York, working over the years as a manager of a cafe, the operator of two hotels and even the manager of a bowling alley, before dying at the age of 67.

—————————————————

Today, if Joe Gerhardt is remembered at all, it’s for two things: his monumentally poor hitting season of 1885, and his prolific work in the field.

Nemec, in a sidebar in The Great Encyclopedia of 19th Century Major League Baseball, identifies Gerhardt’s .155 batting average in ’85 as the worst of any player in the century that played 100 or more games in a season. But is that an accurate standard, considering that National League teams didn’t begin to play as many as 100 games in a season until 1884?

Using baseball-reference.com’s sorting function and the site’s standards for qualifiers for each individual season, there were actually 11 batters who had worse batting average’s over a season than Gerhardt’s 1885 numbers.

The worst two seasons were both turned in by Deacon White’s brother, Will White, who batted .136 in 1879 and .142 a year earlier. White could be forgiven, though, since he was a pitcher, winning 73 games in the two years combined. In the days one one-man rotations, most pitchers had enough appearances to qualify for the batting title, and most pitchers were also decent enough hitters to not embarrass themselves.

But think about that 1879 season . . . it was also the year that Gerhardt dropped to .198, giving the Reds a very unproductive end of the order. Is it any wonder that Gerhardt was the one that got the boot at the end of the year?

Most of the others on that list were middle infielders, giving strength to the argument that good fielding wipes away sins at the plate. Not any more, though. In the 21st Century, there have been only four sub-.200 seasons among qualifiers, and in each case, the player in question hit no fewer than 19 home runs. Mark Reynolds, in 2010, batted .198 and struck out 211 times, but he also hit 32 home runs and drove in 85. Modern teams apparently are more likely to accept a lousy batting average in exchange for power, rather than fielding finesse.

In the field, Gerhardt continues to hold one particularly impressive record, the career mark for fielding range at second base (putouts and assists per game) at 6.46. The top nine on the list are all from the 19th Century, which suggests the relative importance of infield play in the first quarter of a century of the major leagues. Gerhardt only ranked first in the league in the category a handful of times in his career, so his career ranking is a testimony to the fact his skills didn’t diminish with age; his final season was statistically his best.

—————————————————

On March 11, 1922, Gerhardt died of a heart attack on his way to work in Middleton, N.Y. His passing was briefly noted in the March 16 edition of The Sporting News, but the final eulogy was accorded to New York sportswriter John M. Foster, who two weeks later penned a piece with the headline No Second Baseman Ever Excelled Joe Gerhardt. That, and a concluding paragraph considering the merits of a number of second baseman and concluding with the line “None had anything on ‘Move Up Joe’ Gerhardt,” show up in short biographies of the second baseman.

Reporters and columnists, of course, don’t write the headlines that appear on their stories, and a close reading of the column doesn’t encourage the idea that the author was claiming Gerhardt to have been the best at the keystone sack. The meandering piece does point out Gerhardt’s popularity, but midway through devolves into a somewhat humorous commentary on the regional rivalry of Cincinnati and Louisville (two cities in which Gerhardt played) before returning to the point. What’s missed about the final paragraph is that even Foster didn’t claim that Gerhardt was the best:

He played second base with the smoothness of Bid McPhee of Cincinnati, when McPhee was great, but he couldn’t cover the ground that Bid did . . .

In the end, Joe Gerhardt doesn’t exactly fit the role of a 19th Century Mario Mendoza. Clearly, he was one of the leading fielders of his day, and just as clearly, despite a promising start, he at some point lost the ability to hit major league pitching consistently. Still, that didn’t seem to be as crucial to his value in his own day as we might expect, weighing these matters from our perspective of one and a quarter centuries later.

More than anything, Gerhardt appears to have been the right man at the right place in the right time.

New York was the birthplace of what would become America’s game, but at the major league level, the game had been dominated for years by teams from Boston, Chicago, even Providence. The Giants energized interest in the sport in the nation’s largest city, and Joe Gerhardt was able to ride the crest of that wave of excitement.

He was never a superstar, but with his trademark chatter and his ease at dealing with the media, he was, for a brief time, New York’s chosen son.

Sources:

Major League Baseball Profiles 1871-1900, Volume 1, by David Nemec

The Great Encyclopedia of 19th Century Major League Baseball, by David Nemec

Players and Teams of the National Association, 1871-1875, by Paul Batesel

A Biographical Dictionary of Major League Baseball Managers, by John C. Skipper

The Sporting News, March 30, 1922 (No Second Baseman Ever Excelled Joe Gerhardt, by John M. Foster)

May, 1885 editions of the New York Times, the New York Sun and the Indianapolis News