Where to start? How about at the beginning?

I first discovered Ars Longa Art Cards in what I imagine to be the usual way: surfing around eBay, looking for something interesting to collect.

Let’s face it, the trading card hobby has grown boring. I’m old enough to remember when it was still a child’s pastime, before the Baby Boomer generation carried it to adulthood. But I’ve also seen the steady decline in the last two decades, when a new generation of children never saw the point in collecting, and wouldn’t have been able to find the cards at their local drugstore if they had. But then, who needs to buy a pack of baseball cards when it’s all there on eBay? Why spend all summer piecing together a complete set when with one click of the mouse you can own it instantly? In that way, eBay is both the best thing that’s happened to the trading card collector . . . and the worst. At some point, I realized that I’d stopped being a collector. I’d become an accumulator.

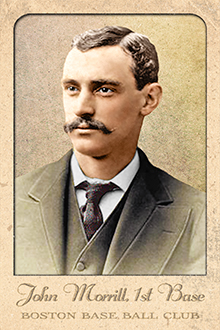

But with baseball card stores now as rare as pennants in Chicago, eBay is where you go. And it’s where I was that afternoon, scrolling past one of those “If you bought this, you might like this” features on my eBay home page, when it caught my eye. It looked like a tobacco card . . . John Morrill . . . Ars Longa . . . 1880s . . . none of which meant anything to me.

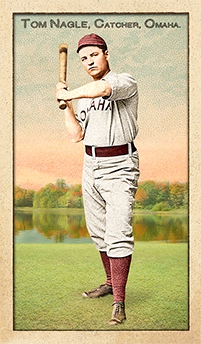

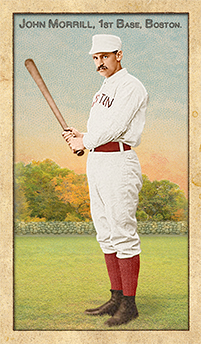

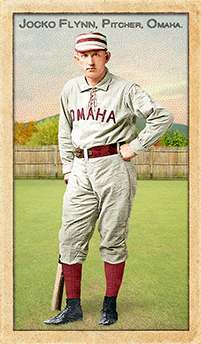

Still, I looked at the auction, and the other Ars Longa auctions available. It wasn’t love at first sight. The images were beautiful, but the players were unknown to me. I put down some minimum bids on several of them, and forgot about it. A few days later, I discovered that I’d won three of the lots. A few days after that, they were lined up in front of me . . . Morrill, Tom Nagle, Jocko Flynn, looking like they could have been pulled yesterday from a fresh pack of 19th Century cigarettes, but so much more than that. The vibrant colors, the sharp presentation of 125-year-old photographic images taken from the epic Old Judge set, thin cardboard strips that were remarkably crisp and sturdy, and Ars Longa’s distinctive “manual distressing”: a little wear on the corners, some artful age-staining, but nothing to take away from the image itself.

I was hooked. And I’ve bid on many more Ars Longa cards since then, from all five of its active series. But as much as I admired Jesse Loving’s little works of art, I still didn’t know these guys.

So I did a little research . . .

Tom Nagle gives the camera a menacing stare in his Ars Longa 1880s card. But that was just wishful thinking . . . like most catchers of his day, his primary contributions came in the field, rather than at-bat.

Nagle hit only .248 in 1888, the year he posed for the Old Judge photographers. But he had a breakthrough season the following year, batting .298 as the team’s regular catcher while handling future major league pitchers Kid Nichols, Dad Clarke and Phil Nell. Omaha roared to the Western Association pennant by eight games over runner-up St. Paul, and Nagle was ticketed to Chicago to play for the White Stockings.

After a decent rookie season in which he batted .271 as back-up to Kit Kittridge, things fell apart for Nagle. Late in 1890, he threw out his arm, and early in the following season he jumped the team to return home to Milwaukee to get married. Cap Anson, the White Stockings manager, was less than sympathetic over the call of true love, and when Nagle failed to hit upon his return, he was cut.

Despite losing his left leg to diabetes late in life, Nagle lived to the ripe old age of 80, and had a long career with the Wisconsin Central railroad after his playing days.

So why did I take a flyer on a relatively nondescript minor league catcher? Honestly, I think it was his team’s name. I mean, the Omaha Omahogs? They don’t name teams like that any more! And what a perfect name for a team from the Heartland. Later, I learned that Omaha’s alternate nickname was the Lambs. I assume that was saved for the days on which they lost.

And what a great card! Note that it was conceived of having taken place on an autumn day just above a riverbank (you can see the reflection of the trees in the water).

John Morrill could do it all. Everything. He was regarded as one of the most stylish-fielding first basemen in the National League, but during his career he played every position on the field. He was a player-manager and a home-grown Boston favorite. He broke into the NL in its first season and was a regular in the Beaneater lineup for 13 seasons. When he retired, after a few years as a sportswriter, he became partners with George Wright in a sporting goods business at which he remained for 35 years. Late in life, he became an excellent golfer and the chairman of the New England Senior Golf Association.

Morrill accomplished seemingly everything except to write his name in big, bold letters across the history of 19th Century baseball. The early years of professional baseball are filled with men like Morrill, good, solid players who established themselves over many seasons, minor stars, if you will . . . but who just aren’t remembered today.

But in his time, Morrill certainly had many memorable accomplishments. After starting at second base as a rookie, he was the regular third baseman in 1877 as Boston won the pennant, then moved to first base the following year as the Beaneaters repeated as champions. He was the choice to replace long-time manager Harry Wright in 1882, although he gave up the managerial role the following spring to second baseman Jack Burdock. But when Burdock decided by midseason that he couldn’t handle the job, Morrill took the reigns and guided Boston to a 33-11 record down the stretch and another pennant. Along the way, he batted a career-high .316, was second in the NL in slugging (.525) and pitched the lone complete game of his career.

Sadly, the man they called “Honest John” never hit those heights again, and things fell apart after Boston paid a record $10,000 to Chicago in 1887 for Mike “King” Kelly, one of the 19th Century’s most luminous stars. Kelly was also handed Morrill’s job as player-manager, and the two veterans never got along. Perhaps it was the specter of one’s predecessor still hanging around at first base, but whatever the reason, Kelly reportedly ran Morrill down at every turn. Morrill responded with career highs of 12 home runs and 81 RBIs in 1887, and even regained his managerial post later in the year. But by the following season, the in-fighting had taken its toll, and Morrill’s batting average dropped to a dreadful .198, the lowest in history for a first baseman with enough plate appearances to qualify for the batting championship. When Boston acquired first baseman Dan Brouthers and four other star players in an off-season fire sale from Detroit — just before the Wolverines disbanded — it was no surprise when Morrill was shipped to Washington prior to the start of the 1889 season.

Oddly, Morrill did have one last moment in Boston, the city in whose environs he spent his entire life. He returned in 1890 to play two games with the Boston Reds, during the lone season of the Players League. As little contribution as he made, he could still say he was part of a fourth pennant-winning team.

Morrill has a steely-eyed gaze in his Ars Longa card, his white uniform looking crisp and clean against a panoply of trees turning to fall colors behind a stone wall, the grass beginning to yellow in the autumn setting. It’s that mix of Old Judge photography and Buchner Gold Coin backgrounds, all enhanced in the Ars Longa fashion, that make the 1880s cards such miniature works of art.

Jocko Flynn doesn’t look particularly happy in his 1880s card . . . fist on hip, a mildly sour expression on his face. But what can you expect? How are you gonna keep them in Omaha when they’ve seen the bright lights of Chicago?

Jocko can be categorized a lot of ways: a one-hit wonder, a star that burned very bright and burned out very fast, a cautionary tale, a minor American tragedy. What can’t be disputed is that he had the greatest year ever recorded for a player who pitched only one season.

Flynn’s rise in baseball was meteoric. In 1884, at age 19, he starred for his local team in Lawrence, Mass., assisted by his personal catcher, boyhood friend George “Prunes” Moolic (the derivation of whose nickname is, sadly, lost to time). The following season, the pair moved on to the New England League, where the right hander won 25 games for two teams and caught the eye of the White Stockings’ Cap Anson. Chicago was the reigning National League power in the mid-1880s, but in winning the 1885 pennant, star pitcher John Clarkson‘s arm had been taxed to the tune of 623 innings. Anson hoped to add a third arm to a rotation that also included Jim McCormick, enough so that he agreed to sign Moolic as well.

In the spring of 1886, Flynn quickly made an impression. The Chicago Tribune got this scouting report from shortstop Ned Williamson: “Flynn seems to have curves, drops, in and out shoots, and slow balls down to a point where he can handle them just about as he wants to. He has good speed, too, and covers his position as well as any pitcher we ever had.”

Despite his diminutive stature (5-foot-6, 143 pounds), Flynn put up big numbers during his rookie season. He was 23-6, with a 2.24 earned-run average and 146 strikeouts. Although Clarkson (36) and McCormick (31) both won more games, Flynn led the NL with a .793 winning percentage, as the White Stockings rolled to another pennant.

But Flynn didn’t pitch in that fall’s World Series, in which Chicago was upset by the American Association’s St. Louis Browns. The primary reason was that he’d thrown his arm out.

But a secondary issue was his night-time activities. Chicago was a hard-drinking town, even by the standards of the day, and Flynn had apparently begun running with a fast crowd. At midseason, he was one of seven players that Anson fined for “breaking the rules relating to temperate habits while off duty.” In his 1900 memoir, A Ball Player’s Career, Anson credited Flynn with being “a good fellow,” but alluded to the pitcher’s “attempting to keep up the clip with so-called friends, found the pace much too rapid for him and fell by the wayside.”

Flynn’s predilection for hard living might have been overlooked had his arm bounced back, but it never did. He played one game in 1887, in the outfield, and had to leave when the first ball he handled in right field split his finger. He was released soon after.

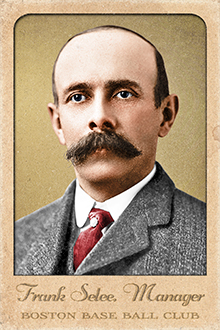

Flynn’s one last shot in professional baseball was likely the result of an old friend giving him a chance. The manager in Omaha in 1888 was Frank Selee, who not long after moved on to Boston for a managerial career that would land him in the Hall of Fame. He was also Flynn’s first manager, in Lawrence. Flynn split two pitching decisions for the Omahogs, but by then it was apparent to management he’d never return to form.

After knocking around in various low minor leagues for two more years, Flynn returned to Lawrence at the age of 25. He married, and moved between various jobs ; at one point, he and Moolic each owned and ran bars. At 42, he died of pneumonia, only hours before his wife also passed, leaving four orphaned children.

So, was it the drink that did in Jocko Flynn, or merely a bum arm? For someone who had a fairy-tale introduction to the major leagues, he seemed fated to continue paying for that bright moment for the rest of his life. Consider that thousand-mile stare in his Ars Longa card . . . is he wondering “How did I get here?”

So, what really drew me to Ars Longa? It would be simple enough to say that the cards are gorgeous, that you can get lost assimilating every little detail and every vibrant color. But more than that, it’s that every player pictured has a story. Some perhaps more riveting than others, but from the future Hall of Famers down to the journeymen, they all have a story. And for the average baseball fan, they’re stories to which we’re rarely exposed.

Perhaps it’s because what’s considered the modern era of baseball so neatly begins with a new century, but the professional game in the 1800s seems too often to be regarded as a foreign country, one that bears no resemblance to what came after. To be sure, the first quarter century of the professional game saw constant change, an annual tinkering with the rules, the distances and the mechanics of the game that finally resulted in the perfect mix we know today. The tinkering has never really ended; changes are made whenever either pitching or hitting gains too much preeminence, but the game that was delivered to the beginning of the 20th Century is one we easily recognize today.

Yes, 19th Century baseball was different, but what wasn’t different was the people involved. Very quickly, a class of professional ball players developed along with the game. Perhaps they were a little more colorful than those taking part in today’s corporatized game. There was nothing alien about them, yet with the exception of a handful of people like Mike Kelly or Cap Anson, the average fan has found it easy to ignore an exciting time in America’s Game.

They all had stories, just like 19th Century baseball as a whole is a very large, interesting story. When I began collecting Ars Longa cards, I began immersing myself in that story. Each new card, rather than just being an excuse to tick another item off a want list before immediately sticking it away in a cardboard box, became a new experience, a new reason to find out more. And suddenly, I was a collector again.

Of course, Ars Longa already knew this . . . take some time visiting this web site, check out the card images, but also read the well-done bios of players from an age of baseball that was wilder and woolier, but also quite familiar.

In a hobby that’s become predictable and too infrequently takes you back to the kind of joy that made you a collector in the first place, it’s a pleasure to enjoy something new, and fresh and vibrant . . . even if it was inspired by something quite old.

Sources:

The Great Encyclopedia of 19th Century Major League Baseball by David Nemec

Major League Baseball Profiles 1871-1900, Vols. 1 and 2 by David Nemec

The Rank and File of 19th Century Major League Baseball by David Nemec

baseball-reference.com

Jocko Flynn by Justin Murphy, The SABR Baseball Biography Project (sabr.org )