One day in 1970, a customer walked into a Boston bookshop and inquired of two men working there about purchasing a book about baseball cards. When Brendan Boyd and Fred Harris realized there was no such book that they could sell, they eventually came to the conclusion that they should write that book themselves.

So, armed with no writing experience, a few contacts in the publishing world and a stack of baseball cards, they did just that.

The Great American Baseball Card Flipping, Trading and Bubble Gum Book, published in 1973 and several times afterward, was an instant classic. It was also one of the most significant books about the hobby, because it was less about baseball cards and more about the experience of growing up as a baby boomer in the ’50s and ’60s. Baseball and collecting baseball cards were an essential part of that experience. With wit, warmth and more than a little snarkiness, Boyd and Harris returned a generation of grown-up collectors back to the hobby of their youth.

The book was divided into three parts, opening with a reminiscence of a baseball-card-driven childhood in the ’50s, followed by a visit with Sy Berger and an impromptu history of Topps at its corporate offices, and ending with the heart of the book, “Profiles.” The two authors divvied up their baseball cards and wrote a string of essays inspired by them, Boyd handling the American League and Harris the National. Some of the pieces were about the specific card, some were about the specific player pictures, others were on themes inspired by the pasteboard art. Some were a page long, some were a single line, but just about anyone who owned the book will tell you they’ve gone back again and again to re-read this or that portion of it.

And there was one entry in particular that stuck with me.

It was devoted to Gus Zernial of the Philadelphia Athletics and his card in the 1952 Topps set. Maybe you know the card, but reading the book as a teenager in the ’70s, I’d never come across it. But it’s one of those cards that makes your jaw drop. There’s Gus, holding his bat in his right hand . . . with six baseballs attached to its barrel, looking like the branch of a particularly robust fruit tree. Meanwhile, Gus has the thumb and forefinger of his left hand shaped in a circle with his other fingers unfurled, in the universal language of A-O-K.

If you sort through a pile of cards featuring portraits, posed pitching shots and players with their bats on their shoulders, this one would stand out every time.

Boyd, in his analysis, was just as gobsmacked:

This is one of my all-time favorite cards. How do you suppose they got those baseballs to stay up there anyway? Nails? Scotch tape? Postage stamp hinges?

And why do you think Gus is giving us the high sign? Is he trying to assure us that everything is OK? Is he trying to indicate to us that he thinks the Athletics are a big zero? Does he want a cinnamon doughnut to go?

And why is he wearing a pink undershirt?

And what the hell is it supposed to mean, anyway?

Boyd goes on to point out that Zernial was one of the class of bulky sluggers of Eastern European ancestry that seemed to dot the roster of just about every American League team in the 1950s. Beyond that, he had little explanation about what Gus and his baseball tree were all about.

Didn’t matter . . . I thought it was one of the neatest, most surreal things I’d ever seen come out of a wax wrapper with a slab of gum. I had to have a copy . . . but this being the pre-Internet era, you couldn’t just go on to eBay and do a “Buy It Now” purchase.

About 10 years later, I found a placeholder in my collection for the Zernial card: In 1983, Topps went to great lengths, trouble and expense to do an official reprint of the 1952 set, an effort that pretty much fell flat. Within a year, Topps was trying to unload the balance of the product for $25 a set through a national advertisement in USA Today. Three decades later, the unopened sets are finally pretty valuable. The Zernial card looked good, but the reprint set was on thin stock and sized at modern dimensions. It just wasn’t the same as the thick, larger-sized originals.

I finally got my ’52 Zernial another couple of decades later, on one of the rare West Coast appearances by the National Card Collectors Convention. There it was, just sitting on a dealer’s table in reasonably good condition for a reasonable price. It’s held an honored place in my collection ever since.

The reality behind hobby legends like this aren’t usually as interesting as the speculation, but the true story of the Zernial card is kind of instructive.

In May of 1951, Zernial had only been in Philadelphia for a few weeks, having been acquired by the Athletics from the Chicago White Sox in an early-season trade for Minnie Minoso. The A’s were finishing up a home series with the Yankees on Sunday, May 13, and Zernial hit a pair of home runs, off Spec Shea and Fred Sanford. After a day off, the St. Louis Browns rolled into town, and in the series opener Zernial had a first-inning, inside-the-park home run off Dick Starr and added another shot in the ninth, off Ned Garver. On Wednesday, he victimized Cliff Fannin and Duane Pillette.

By now, Gus was getting plenty of attention, and on Thursday an enterprising photographer from a wire service arranged to shoot a picture to commemorate Zernial’s feat of six home runs in three games. The secret of how the balls were attached to the bat has apparently been lost to the ages. Epoxy? Elmer’s Glue? Contact cement? Alas, we’ll probably never know, but the picture was taken and sent out on the wires to be used by newspapers all over the baseball-playing world.

For good measure, Zernial went out that day and hit his seventh home run in four games, off the Browns’ Don Johnson. He added 26 more over the course of the season and led the American League with 33 home runs.

Topps’ 1952 set was ground-breaking, much larger than the company’s small inaugural set of the previous year, bigger-sized cards than had ever been seen and real color photos . . . well, colorized black and white photos. Needless to say, the Brooklyn company didn’t have a battalion of photographers at that point, so a number of pictures used had been bought by photographers shooting for the wire services. And that’s how Gus, his baseball-bearing bat and his pink undershirt, ended up in the most famous set of the latter half of the 20th Century.

About that undershirt . . . why pink? As you can see, the original picture was black and white . . . apparently someone at Topps’ art department must have thought that the pink complemented the other colors in the . . .

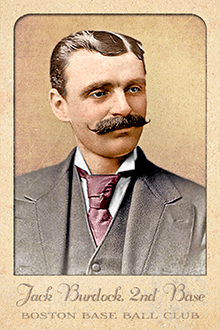

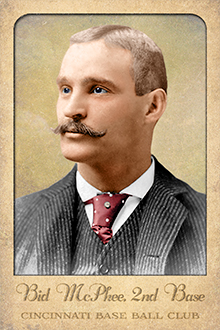

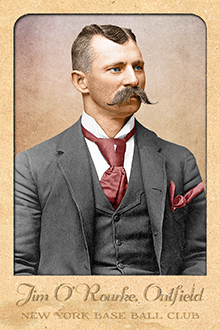

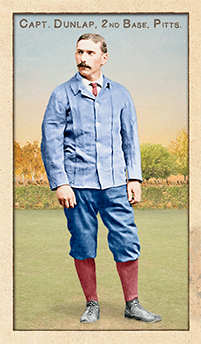

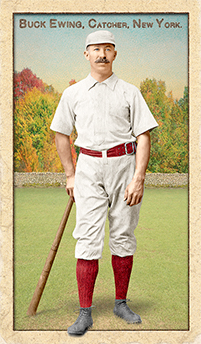

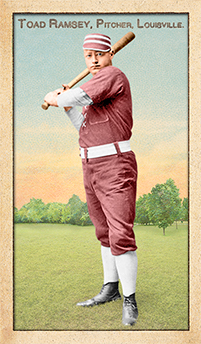

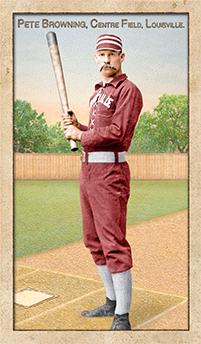

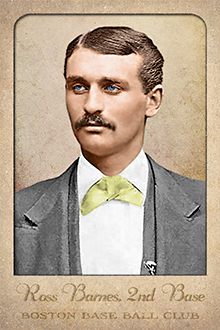

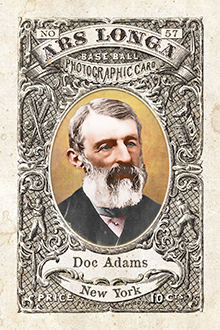

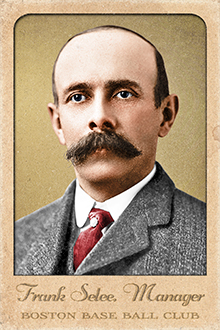

Waaaaait a minute . . . it just occurred to me . . . all of those attractive maroon, scarlet and garnet ties that are featured on players in Ars Longa’s Pioneer Portrait II series, was that all just an aesthetic decision by Jesse to add some vibrancy to a stuffy pose? Huh! Well, they look great . . .

—————————————–

So why am I taking up so much space talking about a 60-something-year-old baseball card on a site devoted to art cards of the early days of professional baseball? It’s because for the longest time, I thought that 1952 Topps Gus Zernial was the coolest card ever. Until recently . . .

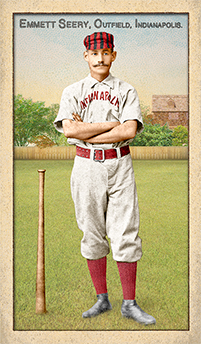

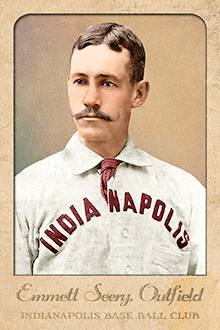

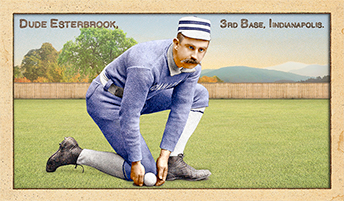

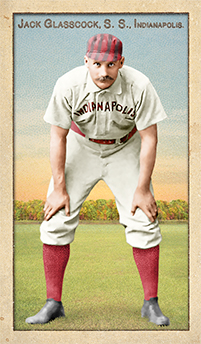

Ladies and Gentlemen, let me introduce to you Mr. John Emmett Seery, originally of Princeville, IL, lately (well, as of 1887) of Indianapolis, IN, And his friend, Mr. Bat, originally of Louisville, KY (probably), and also lately of Indianapolis.

I will admit that the first time I laid eyes, briefly, on Emmett Seerey’s The Beginnings: 1880s card, I didn’t notice it. It was early on in my introduction to Ars Longa, and I spent a lot of time on the web site, surfing through image after fantastic image of Old Judge photographic subjects turned into colorful, pastoral presentations of the ballplayers of the day. Maybe I noticed it on a second go-around.

But there he is, standing in an Ars Longa-generated field, arms crossed, a disinterested — almost annoyed — look on his face, replete in red stockings and a plaid Indianapolis cap. And there, standing next to him, is his bat.

There’s no way that doesn’t make a person smile. Whether it’s the complete denouncement of balance and/or gravity, or the elevation of a piece of equipment to a starring role, that’s just way cool.

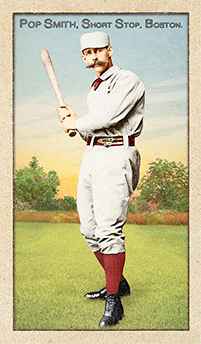

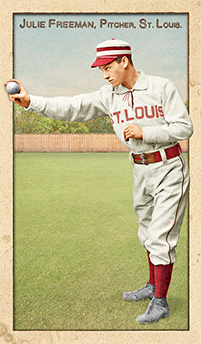

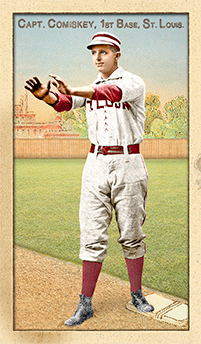

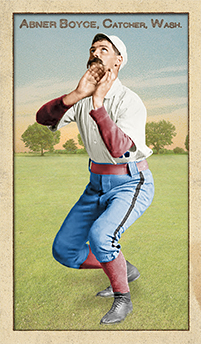

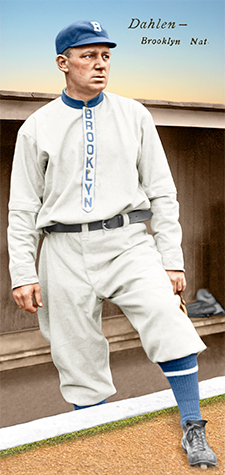

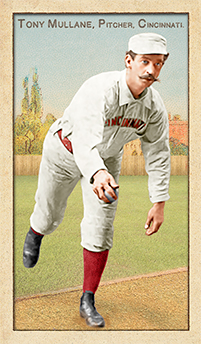

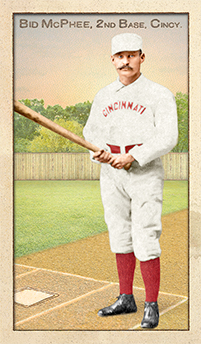

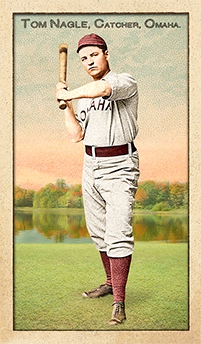

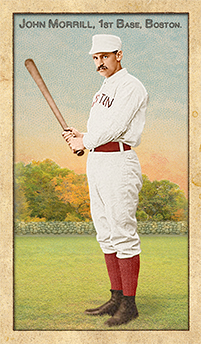

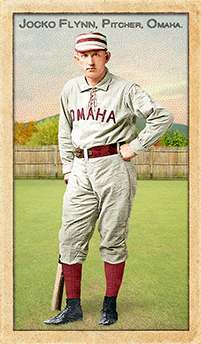

Cards like that of Seerey are examples of what the photographers who took the pictures for the Old Judge card sets were able to accomplish. It’s not overstating things to say that they created the modern baseball card pose.

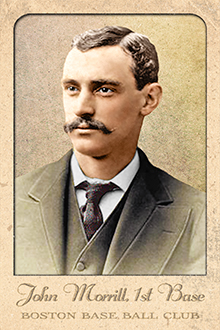

Consider what had come before: portraits and team shots. Photographers either lined the whole squad up for a group picture, or took portraits of the manner used in the making of Ars Longa’s Pioneer Portraits II set. Sometimes portraits were taken of each member of a team and then cobbled together as a composite team picture.

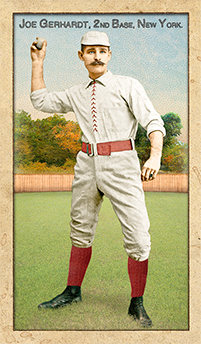

The creators of the Old Judge set, whether an art director at Goodwin and Co. or the photographers themselves (Goodwin employed 18 different photo studios in the East and the Midwest from 1886-89), seem to have understood that baseball was inherently an action-filled subject. I know, I know, that’s not something of which baseball gets accused in this day and age, but it is inherently full of motion. The Old Judge photographers, using what they had at their disposal in their studios, represented that motion: players moving into position to make a catch, sliding into a base, getting ready to swing a bat or pitch a ball. Sometimes those balls were clearly hanging from a string in the studio, but it’s the effort that counts. Sometimes the pictures featured two players, acting out a slide into a base, or an umpire’s call.

A hundred years later, that form of “posed action” was still the presentation of choice in the world of baseball cards. It’s the kind of pose that collectors who grew up with Topps in the ’50s and ’60s came to associate with their little pasteboard tickets into the world of major league baseball.

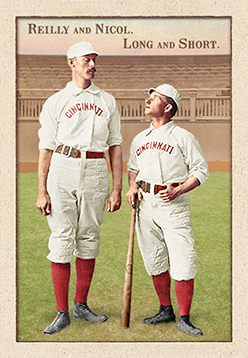

The Old Judge photographers (or at least one of them) had a sense of humor as well. The Seery card is the best example, but there were others as well. Paul Hines had a version of his Old Judge cards featuring the same pose that Seery adopted, with a gravity defying bat and a look on his face that suggested nothing out of the ordinary was happening. Art Whitney posed with a puppy. And lanky John Reilly and diminutive Hugh Nicol, teammates on the 1887 Cincinnati Red Stockings, were brought together for a Mutt-and-Jeff pose labelled “Long and Short.”

That doesn’t even include the unintentionally humorous pictures of ball players trying to mimic actual play by holding a stilted pose in a studio.

As for Seery himself, it’s possible that this pose is for what he’s most famous (keeping in mind that “fame” here is a very relative term). As a player, he’s only known by baseball fans that have deep interest in the 19th Century. Which is a shame because, as ordinary a player as he might have been, he was actually something of a Renaissance Man. He played chess, was a musician and sometimes acted in light opera during his offseasons in Indianapolis.

On the field, Seery’s career was constantly shifting between up and down. A fleet-footed outfielder, he got his big-league break with Baltimore in the Union Association in 1884, leading his team with a .311 batting average. But the UA folded after a year. The following year, he turned up with the National League’s St. Louis Maroons, and in 1886 led the NL in both games played (128) and strikeouts (82).

The Maroons moved to Indianapolis for the 1887 season and Seery responded with three solid years. His batting average was still anemic the first two years, but he had a solid on-base percentage as one of the league leaders in walks. In 1888, he stole 80 bases, two fewer than league-leader Dummy Hoy of Washington. The following season, he broke through with a .314 batting average.

Seery’s career took a downturn in 1890, however, which is strange given that talent was at a premium that season with three major leagues. John Ward, in stocking his own Players League team in Brooklyn, filled his outfield entirely with players from Indianapolis – Seery, Jack McGeachey and Ed Andrews. None of the three could break .253 at bat, with Seery the worst at .223, but at least he had an excuse: he missed 30 games due to a bout with malaria.

The Players League folded after one year, and Seery found himself in Cincinnati in 1891, where he batted a solid .285. The American Association itself was no longer solid, however, and it folded at the end of the season. When Seery failed to hit with the Louisville Colonels the following season, he was released at midseason and that ended his major league career.

After his days in baseball, Seery moved to Florida and owned a pineapple plantation. He died in 1930, in Saranc Lake, NY, the famed tuberculosis sanitarium where Christy Mathewson also spent his last days. And what we’re left with is the impression of a man who had a sense of humor suitable to pose with a bat as his companion.

Silly, perhaps, but it’s supposed to be fun, right? And a little light-hearted? To the modern eye, the Old Judge set may look a bit cheesy, with its stock studio backgrounds and it’s horsehides hung with string. But what it accomplished, even if unintentionally, was to create an iconic style for picture cards of famous athletes. Some 138 years later, it still hits all the right notes.

—————————————–

Sources:

Major League Baseball Profiles, 1871-1900, Volume 1 by David Nemec

The Photographic Baseball Cards of Goodwin and Company (1886-90) by Jay Miller, Joe Gonsowski and Richard Masson