If you’re a fan of the 19th Century and Dead Ball eras of baseball (and if you aren’t, you probably aren’t reading this), then you may be frustrated by the lack of movement in getting players from that period enshrined in baseball’s Hall of Fame. It seems like the Hall has shut its doors on the old timers.

Well, not exactly shut them . . . every few years the door pops open a few inches.

It used to be a lot simpler for the average fan to follow. The Baseball Writers Association of America voted on the recently retired, and the Veteran’s Committee considered those that time had almost forgotten. But in 2010, the Hall broke the Veteran’s Committee into three different groups. Candidates from the 19th Century fall under the consideration of the Pre-Integration Era Committee. Specifically, that means that every three years a ballot of 10 persons is drawn up from players, executives and other significant figures — including those from the Negro Leagues — from a period covering roughly 80 years, and then voted upon by the committee, with the usual three quarters of the vote (12 or more of 16) needed for induction.

Pretty slim odds at best . . .

Fortunately, there is a group that hasn’t given up on honoring the stars of the 1800s who haven’t yet gotten into Cooperstown, and it’s just the people you would have expected: The Society for American Baseball Research.

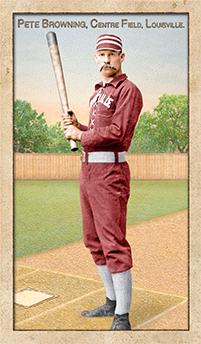

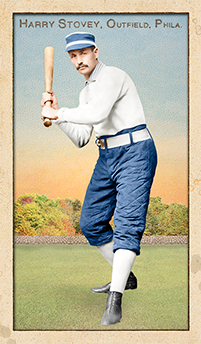

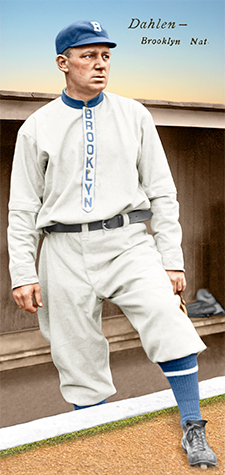

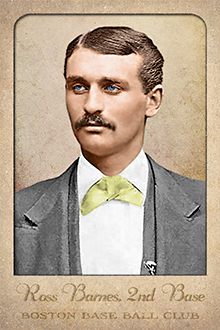

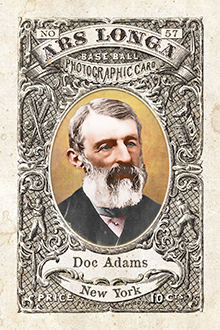

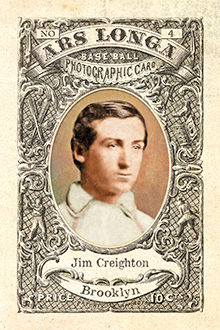

Each year, SABR’s 19th Century Committee holds a vote to determine who would join the ranks of Overlooked 19th Century Baseball Legends. Past winners have included Pete Browning, Harry Stovey, Bill Dahlen, Ross Barnes and Lucius “Doc” Adams. When Deacon White became the second annual winner in 2010, it might well have been a premonition of being voted into the Hall of Fame by the Pre-Intergration Committee two and a half years later.

SABR’s Overlooked 19th Century Baseball Legends, 2009-2014

Top 3 finalists for SABR’s Overlooked 19th Century Baseball Legend for 2015

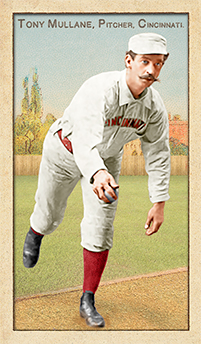

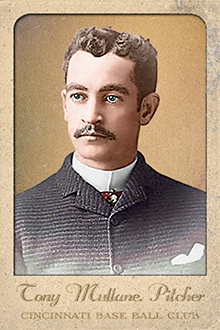

To say that Mullane was a fascinating candidate is putting it mildly . . . and that’s even before you consider his 284 career victories.

Oh, Mullane’s numbers are plenty good. In a 13-year career, eight of which were spent with the Cincinnati Reds, he won 30 games in a season five times, with four different teams. He pitched the first no-hitter in Association history, in September of 1882 for Louisville. His 468 complete games still ranks 10th all time, and given the rarity of that particular statistic in this day and age, his standing is not likely to drop.

But Mullane can’t help but being remembered for a variety of other aspects of his career:

Labor relations: As a general rule, baseball management has never wanted to pay the players any more than they absolutely had to, and the players have never been crazy about that state of affairs.

Mullane, early in his career, was always ready to leap for a better deal. Following a rookie season in Louisville in which he posted a 30-24 record with a 1.88 earned-run average and a league-leading 170 strikeouts, he accepted a better offer from Association rival St. Louis for the 1883 season. The reserve clause was beefed up the following off-season to stop club-jumping, but the new Union Association wasn’t part of that agreement, and Mullane accepted a bigger contract to play for the UA’s team in St. Louis. But Mullane got cold feet when the new league’s prospects began to look a bit iffy (it lasted only one season) and he tried to return to the Browns. In an attempt to avoid any legal problems from multiple contracts in St. Louis, he was instead signed by Toledo.

After a money-losing season, Toledo managment disbanded their America Association team and sold off its stars, including Mullane, to Chris Von der Ahe’s Browns. But despite a written promise to sign a contract with the Browns, Mullane was soon entertaining offers to play for Cincinnati. In the dust-up that followed, the Reds were allowed to retain the rights to Mullane . . . but only after he sat out the 1885 season, a turn of events that would cost Mullane in ways that would only be appreciated many years later.

That was the end of Mullane’s bumping heads with the reserve clause, although he did earn a reputation during his career — whether deserved or not — for occasional “indifference” on the mound. Reds management tried to make sure their ace was as satisfied as possible with his salary, to keep him in the best competitive mood.

Handedness: Mullane’s name recently resurfaced in the sports news due to Oakland’s elevation to the majors of Pat Venditte, one of the few ambidextrous major league pitchers in baseball history. Mullane was the first, although it was more of a novelty than a weapon. There is documentation of him pitching with each hand in a league game on only two occasions, although he developed a reputation for being able to do so. Perhaps it was a trick he brought out for exhibition games.

Good looks: It’s a myth that Ladies Day at the ballpark was created around the desire of the fairer sex to see Mullane on the mound, but by all accounts he was one of baseball’s most dashing players. He was known as the Count and The Apollo of the Box for his aristocratic bearing, as well as Smoked Italian for his swarthy good looks (surprising, really, since he was actually born in Cork, Ireland before emigrating at age 5).

Unfortunately, we can’t really see that from his Ars Longa 1880s card. Mullane appeared in seven different poses in the Old Judge set, but the photographer didn’t capture the “matinee idol” quality in any of them. Flattering portraits of Mullane do exist and I have heard word from Jesse that he is currently working on this image for inclusion in the Ars Longa Pioneer Portraits II Series. (Editor’s note: Card complete and pictured right.)

Race relations: Mullane’s billeting in Toledo in 1884 for the Blue Stockings’ lone major league season coincided with a major historical event, that of Moses Fleetwood Walker becoming the first African-American player in major league history. Unfortunately, Mullane doesn’t come across well in that partnership. Walker shared Toledo’s catching duties with the venerable Deacon McGuire, and Mullane would frequently cross up Walker with pitches he wasn’t expecting. Eventually, Walker told Mullane to throw whatever he wanted, and the two worked well together after that.

Years later, Mullane would credit Walker as a good catcher, but said that he couldn’t like the man because of the color of his skin, a sad commentary on a time that was only one generation removed from the Civil War. Oddly, Mullane had one of his best seasons in 1884, running up a record of 36-26 while the rest of the Blue Stockings’ staff was a collective 9-32.

Mullane’s talents began to dissipate in the mid-1890’s, and he bounced around the league for a couple of season before retiring. An attempt to run a saloon ended up in financial failure, but he had success as a policeman in Chicago, rising to the rank of detective. He died in 1944, at the ripe old age of 85.

So, why are these Overlooked 19th Century Legends not in the Hall of Fame? There’s no one single answer. Doc Adams was a member of the Knickerbocker Club in New York in the 1840’s and did perhaps as much as anyone to shape the game in its early years, but after Abner Doubleday and Alexander Cartwright, perhaps the Hall has had its fill of people that have been proclaimed the “Father of Baseball.” Ross Barnes was professional baseball’s first great hitter, but his best years came in the five years of the National Association, pre-dating the National League.

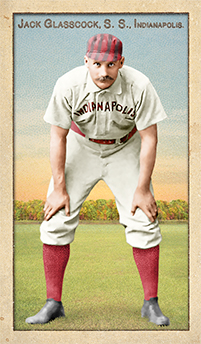

Bill Dahlen may have been a victim of having his career split almost evenly between the 19th and 20 Centuries. He played on four league champions, but in his only World Series appearance, he was hitless in 15 at-bats for the 1905 New York Giants. He batted over .300 only three times in a 21-year career, but his longevity put him near the top in numerous career offensive categories for shortstops. And in the field, he was one of the best his era. His chance could come again this winter, when the Pre-Integration Committee votes again. Three years ago, when Deacon White made the grade, Dahlen was also on the ballot and missed by just two votes.

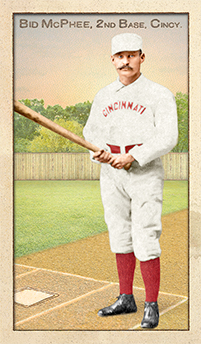

And what of Pete Browning, the original Louisville Slugger; Harry Stovey, one of the 19th Century’s top power hitters; and Mullane? They all have the numbers to qualify, so one can’t help but thinking that they’re tarred by having played most of their careers in the American Association. The only player to be elected to the Hall after playing all or most of his career in the Association was Bid McPhee, and that didn’t happen until 2000.

It’s probably true that the level of play in the Association wasn’t quite at the level of the National League, but it was major league baseball nonetheless. One wonders, though, if that resonates with a 21st Century voter.

And for Mullane, that season in his prime in which he was suspended likely would have easily given him the victories he needed to top the 300 mark for his career. Until Roger Clemens’ steroid issues, that figure was a guaranteed ticket to the Hall of Fame.

But they’ll all get their chance again, slim as it might be. I mean, doesn’t it just seem right that “The Apollo of the Box” should have his mug emblazoned for all to see on a bronze plaque in a museum in a bucolic little town in New York?