“So, what do you do for a living?”

No, I’m not asking, merely musing on the concept of self-identification. If you do something very well under the public spotlight for relatively few years, is that “something” who you are? Even if you spend many more years in later life doing something else?

There are few careers more public than that of a professional athlete. Because of the physical skills required, it’s a career that’s by nature relatively short. At any age at which most of us would consider ourselves to still be young and in our professional prime, an athlete finds that he or she must deal with the second chapter of their adult lives far earlier than the rest of us.

The modern baseball player, if he manages his money well, can find himself in position, after six-to-eight years in the big leagues, to never have to work another day in his life, if he so chooses. Or better put, he can pick and choose his next move to his own liking. But players in the Dead Ball Era, although they made more than the general populace, found things a bit more precarious — particularly when you consider that they would be beyond their playing years when the Depression hit in the 1930s.

For most players of that time, an end to their playing days meant a return to the general workforce. After all, they had bills to pay.

—————————————————————-

In 2007, McFarland published an intriguing book with the less-than-intriguing name of Major League Baseball Players of 1916. The author, an English professor and baseball fan named Paul Batesel, was looking to take a snapshot of the average ballplayer from early in the 20th Century, and did so by researching every player in both leagues to play even a single game that season.

The book reads like an encyclopedia, which, after all, it is. This is not the place to go to read thrilling tales about Walter Johnson‘s 36-win season in 1913. It is the place to go to learn that after retiring in 1927, Johnson raised purebred cattle on a Maryland farm and entered state politics, before returning to baseball to manage the Senators and Indians and later serving as a radio announcer for the Senators. He was only 59 when he died of a brain tumor in 1946.

So what happened to these men, removed from the spotlight between the foul lines?

Not surprisingly, many of them stayed in baseball as long as they could. Minor leagues were independent in the pre-war era (both wars, for that matter), and offered many players a chance to keep competing after the majors had cut them loose. Beyond that, there was always coaching and managing.

Chief Bender was the coach at the Naval Academy in the 1920s, before returning to the Athletics as a coach. “Colby Jack” Coombs didn’t return to his alma mater, but did coach the baseball team at Duke University for a quarter of a century. Larry Gardner did return to his alma mater, the University of Vermont, where he served a baseball coach and athletic director.

Donie Bush spent 65 years in baseball, as a manager, minor league team owner and scout. Hans Lobert had a similar experience, coaching at West Point and with several major league teams before spending the last two decades of his life as a scout.

Max Carey managed in the majors and minors, and helped establish the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League during World War II. Larry Doyle remained in the Giants’ organization after his playing days; when he was diagnosed with tuberculosis in 1942, the team sent him to the same sanitarium in Saranc Lake, N.Y. where Christy Mathewson spent his last days. Doyle’s ending was happier, however. He was released 12 years later and retired to that small lake town.

Sherry Magee gave umpiring a try, but a year after returning to the National League in that capacity, he died of pneumonia at 44.

Half of the “$100,000 Infield” ended up in college coaching. Jack Barry, after several years of running an automobile agency, returned to his alma mater of Holy Cross, where he spent more than three decades, coaching the Crusaders to the 1952 NCAA championship. Stuffy McInnis spent a quarter of a century in college coaching, including a stint at Harvard. Barry’s double-play partner, Eddie Collins, had a long career as vice president, treasurer and business manager of the Red Sox.

Frank Baker went another direction. The home-run hero of the Atheltics teams of the early 1910s returned to his hometown in Maryland and bought up land where he could farm and raise hunting dogs.

Babe Adams, the hero of the 1909 World Series, operated a farm in Missouri before World War II and another in Maryland afterwards. George Gibson and Vean Gregg, both Canadians, returned to their home country to farm.

For some who didn’t stay in baseball, other sporting activities offered employment. Rube Marquard, Heinie Groh and Buck Herzog all worked at race tracks. Ray Schalk ran a bowling alley. Honus Wagner owned a sporting goods business that was wiped out by the Depression; fortunately, the Pirates were ready with an offer of a coaching position.

What of baseball’s most famous double-play combination? Frank Chance, who’d had a history of injuries and ailments during his career, died young at 48, having spent his post-playing days as a manager in the majors and minors. Johnny Evers, like Wagner, owned a sporting good store, and was appointed stadium superintendent in Albany, N.Y. Joe Tinker managed his money well until his Florida real estate investments went belly-up during the Depression. He bounced back, running a pool hall and opening a bar, and worked at the Orlando, Fla. airfield during World War II.

Mordecai “Three Finger” Brown and Stan Coveleski each owned service stations in Indiana, Brown in Terre Haute and Coveleski in South Bend. Ed Walsh retired to Connecticut and was employed by the Meridan Water Plant. Jim “Hippo” Vaughn worked in a refrigeration assembly factory.

Some players did quite well for themselves, financially. Ty Cobb got in on the ground floor of investing in Coca Cola. Bill McKechnie had lucrative land and oil investments in Florida. Gavvy Cravath not only did well with real estate in Laguna Beach, CA, he also served as Justice of the Peace in that city for 36 years.

The Red Sox “Golden Outfield” spread across the country. Harry Hooper spent a quarter of a century as the postmaster in Capitola, CA. Duffy Lewis spent 30 years as the traveling secretary for the Boston/Milwaukee Braves. Tris Speaker made a living out of being Tris Speaker; he was a regular on the banquet circuit and was president of Tris Speaker, Inc., a wholesake wine and liquor company in Cleveland, before retiring to his native Texas.

Fred Snodgrass ran an electrical appliance business in Oxnard, CA, where he also served as mayor. Terry Turner, who patrolled the hot corner for so many years in Cleveland, went on to become the Chief Superintendent of Streets in that city. Heinie Zimmerman ran a speakeasy for gangster Dutch Schultz. Ed Konetchy owned a restaurant and chicken ranch in Fort Worth, Texas.

Zach Wheat did a little of everything. A native of Missouri, he was running a farm in Caldwell County even while playing with the Dodgers, but lost it in the Depression. His post-baseball resume includes managing a bowling alley, serving on the Kansas City police force, running a hunting resort in the Lake of the Ozarks and working in a Wichita defense plant during World War II.

As if fate hadn’t already saddled him with enough to carry, Fred Merkle‘s investments were largely lost in the Depression. Afterwards, he was a partner in a company that made fishing equipment. Slim Sallee may win the award for persistence. After his baseball career was over, he put his money into an ice plant, a service station and a restaurant in his hometown of Higginsport, Ohio. He lost everything when the Ohio River flooded in 1937. He bounced back by tending bar and finally purchasing “Slim’s Cafe.”

The downward spiral of Grover Cleveland “Pete” Alexander after his playing career is one of baseball’s saddest chapters. Dealing with epilepsy, alcoholism and the lingering effects of a World War I shrapnel injury, he lived on the fringes and got by with a series of odd jobs. He did a stint playing with the House of David baseball team, worked in a penny arcade, retold the story of his strikeout of Tony Lazzeri in the 1926 World Series for patrons of a Times Square flea circus, and worked as a security guard at a defense plant, before dying of a heart attack at 63.

And then there were the Black Sox, the members of the 1919 Chicago White Sox drummed out of baseball for their involvement in the throwing of the World Series. If organized baseball had its druthers, they’d recede into anonymity, and that’s largely what they did. Most of them played for a few years on touring teams or in outlaw leagues that weren’t bothered by baseball’s ban, but as their skills diminished they moved on to the next stage of life.

Lefty Williams ran a pool room in Chicago for a few years before moving to California, finally ending up in Laguna Beach, where he ran a garden nursery business. Fred McMullin worked as a carpenter before later making a career as a Los Angeles County deputy marshal. Swede Risberg landed in the Northern California town of Weed, where he operated a tavern for nearly two decades.

Buck Weaver, who proclaimed his innocence to the end and unsuccessfully petitioned baseball commissioner Kennesaw Mountain Landis for reinstatement numerous times, worked in the pari-mutuels department of Chicago racetracks. Happy Felsch opened a grocery store, then later ran a tavern. At 58, he started a new career as a crane operator, one that lasted until his retirement at 71.

Chick Gandil, the man who drove the conspiracy from the inside and is believed to have pocketed the greater portion of the money used to fund the throwing of the games, moved to Berkeley, CA, and became a plumber. Joe Jackson, the man who became the symbol for the American tragedy that was the Black Sox scandal, played for independent teams as long as he could, then retired to his home in Greenville, S.C. For years he ran a successful liquor store before dying of a heart attack at 63.

Eddie Cicotte, a native of Detroit, remained in that city but used another name to protect his family. He worked for the Ford Motor Company until 1944, then spent the last 25 years of his life on a farm near Farmington, MI, raising strawberries. On his death certificate, his occupation was listed as “baseball player.”

—————————————————————-

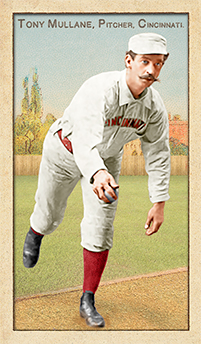

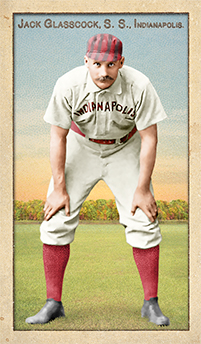

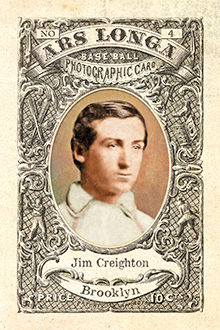

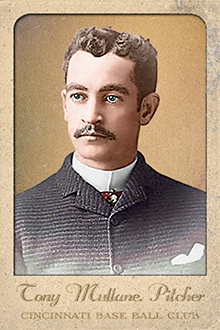

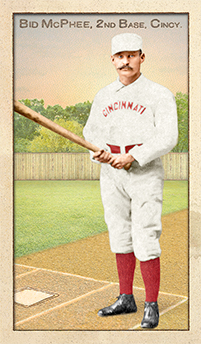

Almost every player listed in this piece has an Ars Longa card. You can view some in the pastoral hues of the Pilgrim series, others with the striking backgrounds of the Diamond Heads ’15 cards. Either way, they look forever young and strong, heroes to a growing sports fandom.

But eventually the spotlight was turned off. And like all of us, they had to pay the bills . . .

Sources:

Major League Baseball Players of 1916 by Paul Batesel

SABR Bio Project (sabr.org)