Is there any sports award that, by its very nature, incites more controversy and consideration than the one given to the Most Valuable Player?

Think about it: it’s not “Player of the Year, ” or “Most Outstanding.” It’s “Most Valuable.” The point is debated annually, and the answer is fluid, depending on the specific circumstances of each season. Consider that Andre Dawson and Kirk Gibson won the award in the National League in back-to-back seasons, 1987-88. Look at the numbers for each player. Then look at their teams’ place in the standings. Same award, but two very different routes to getting there. And, in both cases, the award was deserved.

I was thinking about such things while pouring over the voting records for the Chalmers Award, in Bill Deane’s 1988 SABR-produced booklet “Award Voting.” The Chalmers, given out from 1911-14, was an early precursor of the Most Valuable Player Award, which finally found an official home in 1931 with the Baseball Writers Association of America. But it wasn’t cursed with the words “most valuable” in its title. How did the voters of the day approach their responsibility?

It turns out that the situation wasn’t so different from the one today.

*** 1910 ***

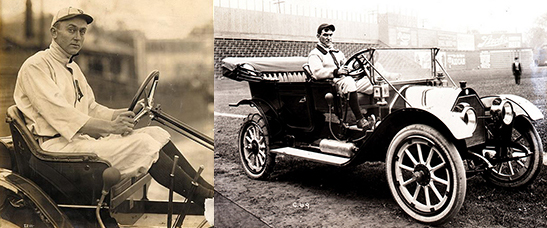

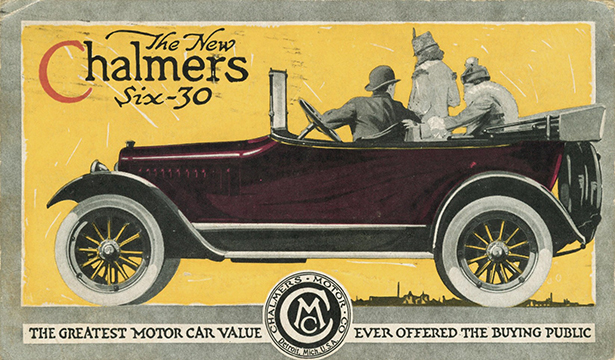

The Chalmers Award arose out of a well-documented marketing fiasco. In 1910, with horseless carriages becoming more and more prevalent on what passed for roads in the United States, Hugh Chalmers saw the opportunity for a little free, high-profile publicity. He announced that the player who finished the season with the highest batting average would be the recipient of a Chalmers “30,” the company’s popular roadster.

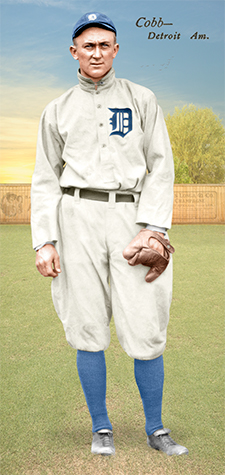

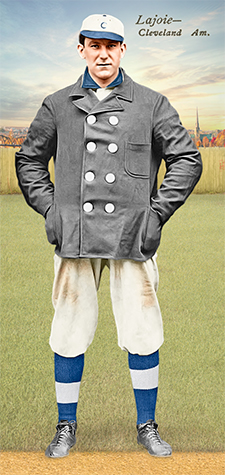

With the National League batting leader, Sherry Magee, some 50 points behind the American League leaders, the competition came down to Ty Cobb, the tempestuous young Detroit outfielder, and Cleveland’s Nap Lajoie, the hard-hitting veteran second baseman. As more attention was focused on the batting race, a summer’s worth of charges of favoritism in official scoring was unleashed, and Cobb, in particular, came under criticism for caring more for personal gain than what was good for the team. How it hurt the Tigers that Cobb batted .532 over the last month of the season has never been explained, but in 1910, athletic competition was primarily about team accomplishments. For some in the media and in the bleachers, striving for individual honors was unseemly. And besides, Cobb already owned a Chalmers “30.”

Things, as it turned out, could only get worse. Cobb, holding a big advantage, elected to sit out the Tigers’ finale. Lajoie, meanwhile, had a doubleheader against hapless St. Louis. Browns’ manager Jack O’Connor started a rookie, Red Corriden, at third base and told him to play back on the outfield grass. That was too much of an invitation to pass up; Lajoie, after hitting a triple in his first at-bat, bunted six times for hits in the two games. In his final at-bat, he reached base on an error. An attempt was reportedly made after the game by Browns officials to bribe the official scorer to change the error to a hit. Why? Perhaps because Cobb was that much hated around the league, perhaps because Lajoie was a respected member of the old guard. Whatever the case, O’Connor’s anything-but-subtle machinations didn’t fool anyone.

As one can imagine, the sorry chain of events left baseball with a black eye. When competing sets of numbers were crunched (remember, there was no automatic updating on the Internet in 1910), Cobb was announced the winner, .385-.384.

Hugh Chalmers at least had enough sense to give each player an automobile, and in an attempt to smooth things over, he came up with a new proposal: beginning in 1911, Chalmers would award an auto to a player in each league who “should prove himself as the most important and useful player to his club and to the league at large in point of deportment and value of services rendered.”

Sounds a lot like “most valuable,” doesn’t it? What was also similar to today was that the voting would be done by members of the media, one from each city in each league. Each writer would vote for eight players, with his top pick receiving eight points, down to one point for his eighth choice.

The award lasted for four seasons, and slips quite nicely into the Ars Longa scheme of things between the 1910-oriented Pilgrims set and the Diamond Heads ’15

So, how did sportswriters handle these issues, a century ago? Any better or worse than today’s voters? Then as now, once the ballots have been counted and the award given, it still comes down to one’s own point of view . . .

*** 1911 ***

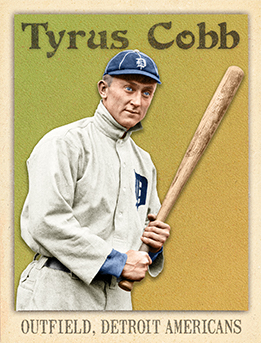

Considering that Cobb was at the center of a controversy about pursuit of individual honors ahead of his team’s success just a year earlier, it’s perhaps peculiar that the Detroit outfielder became the first and only player to win the Chalmers Award unanimously. But how can you argue with a .420 batting average, a .621 slugging percentage, 47 doubles, 24 triples and 127 RBIs . . . all of which led the American League?

While the AL vote was thoroughly one-sided, the National League was the tightest that the Chalmers’ Award would ever see. Only 10 voting points separated the leader from the two players who tied for seventh, and the winning total of 29 was the only time a Chalmers’ winner would receive less than half of the highest possible total.

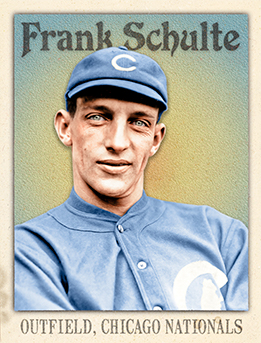

The writers picked Frank Schulte, Chicago’s power-hitting outfielder, who led the league in home runs (21), RBIs (107) and slugging (.534). He edged out Christy Mathewson, who polled 25 points after a 26-13 season.

Did they get it right? It’s hard to argue with the credentials of the winners, although in each case the award went to a player on the league runner-up. Mathewson and Rube Marquard (24-7) were among five New York Giants who split the vote for the NL champions.

One interesting total was that of Miller Huggins, best known as the Hall of Fame manager of some of the greatest New York Yankee teams. In 1911, he was a scrappy second baseman for St. Louis, and he placed sixth in the voting after a season in which he hit .261 and drove in 24 runs. His leadership and defensive skills were no doubt the basis for that support; voters must have figured that anyone who could spark the perennial cellar-dwelling Cardinals to a winning record (75-74) must be valuable indeed.

*** 1912 ***

Reportedly, both Cobb and Schulte asked not to be considered for the award following their victories the previous year, which calls into question whether or not people had figured out the concept of a most valuable player for the season. But, then, how many Chalmers “30s” does one need in one’s driveway?

Apparently, not everyone got the memo, as Cobb polled 17 points, but he wasn’t a factor.

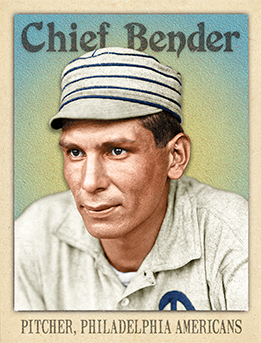

Since 1912 was a year of incredible pitching feats, it’s not surprising that Chicago’s Ed Walsh (27-17), Washington’s Walter Johnson (33-12) and Boston’s Joe Wood (34-5) all finished in the top five. But the 1912 vote was actually a good example of the trouble the voters had when considering pitchers against every-day players (an issue that exists to this day), because no other pitcher picked up a single vote. It was a little better in the National League, where five pitchers collected votes, but between the two leagues, there were eight 20-game winners who couldn’t even manage an eigth-place vote. Larry Cheney of the Cubs and Eddie Plank of the Athletics, a pair of 26-game winners, were both ignored.

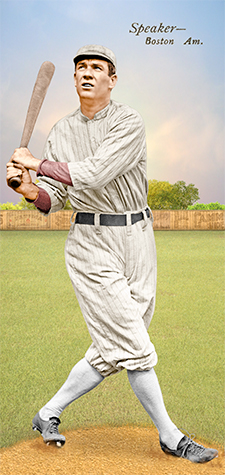

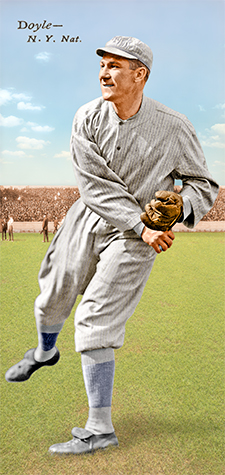

The winners were Tris Speaker of the Red Sox and Larry Doyle of the Giants, the top field players for the two league champs. Speaker, who led the league with 75 extra-base hits and finished third with a .383 batting average (Cobb led at .409), easily outdistanced Walsh, finishing second for the second year in a row, 59-30. Doyle edged Honus Wagner of the Pirates, 48-43.

Did they get it right? If you rule out pitchers, then, yes, probably. But one can’t help but wonder if three pitchers having superior years (each of them finishing in the top three in ERA, victories and strikeouts) may have been one or two too many for the voters. Wood certainly would seem to have had a most-valuable-caliber season, particularly with his team winning the pennant by 14 games, but two other pitchers outpolled him.

In the NL, Doyle and Wagner had close to the same numbers (10 home runs, 91 RBIs, .330 average for Doyle, 7-101-.324 for Wagner), but the Giants did win the pennant.

But here’s something to consider: the Cubs’ Heinie Zimmerman batted .372 and hit 14 home runs, both league-leading totals. In March of 2015, a SABR researcher finished a research project that confirmed that the RBI totals established for the first MacMillan Baseball Encyclopedia in 1969 were wrong, and that Zimmerman had five more RBIs than originally credited, pushing his total to 104 and passing Wagner. Zimmerman, in fact, won the Triple Crown, the crediting of which was delayed, oh, only 103 years.

Would that fact have influenced the voters? Probably not . . . Zimmerman’s overwhelming advantage over Doyle ad Wagner in batting average was already known, and not enough to get him higher than sixth in the voting with 16 points.

*** 1913 ***

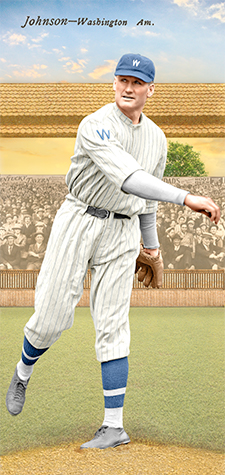

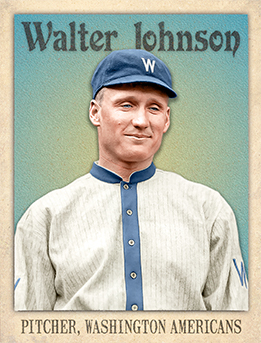

The supposition that too many outstanding pitching seasons might make it impossible for any one pitcher to win a Chalmers Award got support from what happened one year later, when Walter Johnson had the pitching performance of all pitching performances.

The Senators’ star won the AL pitching Triple Crown, and it wasn’t even close. His 36 victories, 1.14 ERA and 243 strikeouts were all so far ahead of the runners-up in each category that it wasn’t even funny. With him, Washington finished second, six-and-a-half games behind the champion Athletics. Without him, they were 54-57.

Still Johnson wasn’t a unanimous pick. He polled 54 points, 11 more than runner-up Joe Jackson, who batted .373 and led the league in hits (197) and slugging (.551).

Jackson did not lead the league in batting however, that honor again going to Cobb at .390 . . . for which he received a total of three points in the voting. Perhaps, in the wake of his 1911 victory, Cobb had again asked voters not to consider him. Or perhaps it was karma in action. Cobb took great delight in telling the story of how he psychologically knocked Jackson out of the 1911 batting race (when both topped .400), by giving the fellow Southerner the impression that Cobb no longer considered him as a friend. Jackson’s average dropped, and Cobb took the batting title. Two years later, Cobb again was the batting leader, but Jackson appeared to have picked up more respect from the voters.

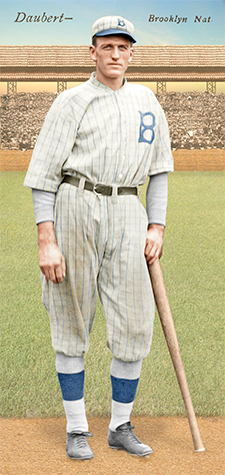

In the National League, Jake Daubert, Brooklyn’s stylish first baseman, won the honor over runner-up Gavvy Cravath of the Phillies, 50-40.

Did they get it right: Walter Johnson? Absolutely. Jake Daubert? Well . . . absolutely not.

Daubert, by all accounts, was one of the finest fielding first basemen of his era, a Hal Chase without the baggage of questionable integrity. He led the NL with a .350 batting average, which helped Brooklyn to a 65-84 record and sixth place.

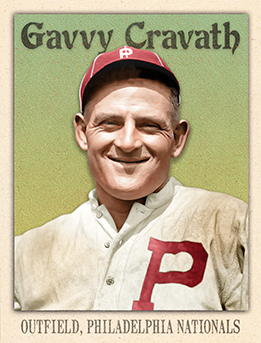

Cravath finished second with a .341 batting average, and that nine points difference cost him the Triple Crown. He led the league with 19 home runs, and blew away the competition with 128 RBIs. His team finished second behind the Giants.

Daubert was well-liked by the fans and the media, and was generally considered the best all-around first baseman in the game. Cravath was considered something of a lummox, not the kind of sleek, speedy fielder that was prized at the time. His power-hitting was considered a bit of an aberration, since he played in Philadelphia’s snug Baker Bowl, with invitingly short distances down the foul lines.

This is what F.C. Lane of Baseball Magazine, one of the most respected scribes of the day, had to say in naming Cravath to the magazine’s annual National League all-star team:

“No doubt the most conspicuous outfielder in the list is Cactus Cravath of the Phillies. This sturdy hitsmith has battered his way to the top by his dizzying success of two-base cracks and home runs. He fell a bit short of Daubert in the popular choice for the Chalmers’ trophy, but he is unquestionably one of the most valuable players in the league. Cravath is unfortunately rather slow in the field, though an earnest and industrious worker. His leaden footed tactics, however, are lost sight of in his tremendous batting, the most valuable of talents in an outfielder.”

You can imagine Lane holding his nose with one hand while typing out praise with the other. The truth was, Cravath wasn’t really such a bad fielder. He was usually among the league leaders in assists for outfielders, and he didn’t make any more errors that his peers. No doubt the perception was that he also didn’t get to as many balls as a speedier outfielder might have.

And, remember, although some teams and organizations did track them, RBIs weren’t an official statistic until 1920. Most of what we recognize as the statistical realities of a century ago have been retro-engineered by several generations of hard-working researchers, pouring over microfilmed play-by-plays of games to make sure the statistics that have been passed down through the decades are accurate. Plus, voters in 1913 didn’t have the benefit of knowing that Cravath led the National League that year in Offensive WAR, OPS, Runs Created, Adjjusted OPS+, Adjusted Batting Runs, Adjusted Batting Wins and Offensive Win %, Heck, I barely even know what any of that means. But I think it meant that Cravath did pretty well.

The sad fact is that poor ol’ Gavvy never got the respect that his offensive output in the deadball era should have earned him. And he should have won the Chalmers that year.

*** 1914 ***

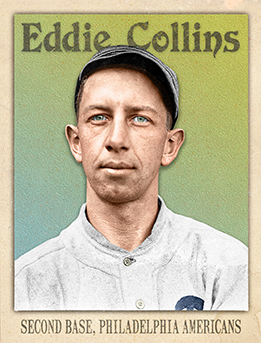

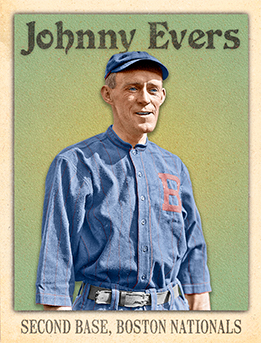

There’s a fairly well known picture of Eddie Collins and Johnny Evers, captains of their respective teams, shaking hands before the 1914 World Series. Any second baseman who ever felt overlooked and underappreciated ought to have a copy of that picture framed and hung over the mantelpiece, because for second sackers, it didn’t get any better than ’14.

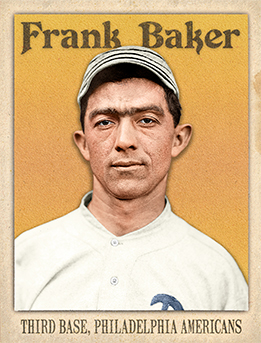

Collins won the Chalmers in the AL with a near-unanimous vote, seven first-place votes and one for second. All four members of the Athletics’ “$100,000 Infield” placed in the top 16 that year, but Collins was clearly the best, leading the league in runs (122), batting .344, stealing 58 bases and anchoring the best lineup in the American League.

Evers won in the NL despite teammates Rabbit Maranville and Bill James nearly splitting the vote, finishing second and third. But how could anyone but the field leader of the “Miracle Braves” be honored, in a season that, more than 100 years later, still gives hopes to any cellar dweller that something magical can happen during the dog days of summer?

Did they get it right? Yes. This was just one of those years when being considered the leader of the best team was going to trump any big numbers. Phillies fans might make the case that Sherry Magee (15 home runs, 103 RBIs, .314 average) had the best year at the plate, certainly more impressive than Evers (1-40-.279). But 1914 belonged to the Braves. ‘Nuf said.

On the American League side, Collins likely benefited from Jackson, Cobb and Johnson having average seasons . . . or at least, average for players of their magnitude. Collins’ closest competition came from Sam Crawford, who led the league with 104 RBIs and 26 triples at age 34.

As a side note, Collins also became the first “MVP” to be sold off before the next season, moving to the Chicago White Sox on Dec. 8, 2014. That was the first step in the dismantling of the first Athletics powerhouse. Connie Mack is renowned as a Hall of Fame owner and manager, but the modern-day owner with whom he has the most in common is Miami’s Jeffrey Luria. Each of those executives broke up championship-caliber teams (twice each!) when the financial numbers no longer made sense.

All eight Chalmers winners are featured on Ars Longa cards; in fact, all four of the American League winners are in both the Pilgrims and Diamond Heads ’15 sets. And of the 86 players featured in those two sets who were active between 1911-14, 54 of them received votes. Lew McCarty? Three points in 1914. Frank LaPorte? Two points in 1911. George McBride? Twelve points, with at least one vote in each season. Eddie Collins? One hundred and forty-three points, the most of any player.

The Chalmers Award was quietly retired after 1914, and the company went out of business by 1923, saddled with post-war debt, and was absorbed into the Chrysler Corporation. It’s name lives on, though, in automotive circles certainly, but also within the world of baseball. Perhaps not in the way that Hugh Chalmers might have chosen, but a place in sports history is still . . . a place in sports history.