The author W.P. Kinsella once came across a few lines in a baseball encyclopedia and was immediately intrigued. The entry was for a baseball player whose entire major league history was encompassed by the numbers “1 game, 0 at-bats.”

Kinsella went on to do extensive research on the player, and ended up using him as a character in his surreal baseball novel, “Shoeless Joe,” which later begat the Kevin Costner film “Field of Dreams.”

And that’s how the world discovered Archibald “Moonlight” Graham.

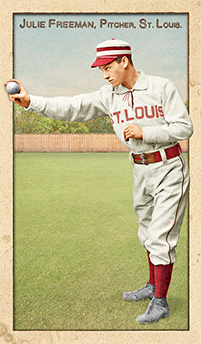

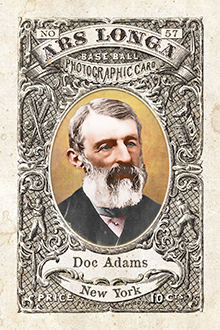

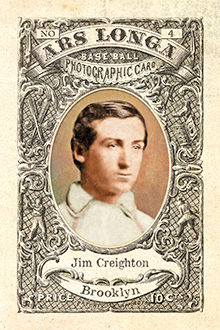

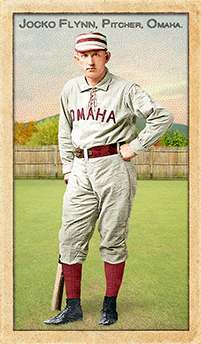

What Kinsella felt about Graham was akin to what I felt when I first handled my copy of Julie Freeman‘s card from Ars Longa’s Beginnings: The 1880s series. A week or so earlier, I’d been completely ignorant of Freeman’s existence, but upon reading the Ars Longa biographer’s description of the St. Louis Browns pitcher and his one-game major league career, I got sucked in, much the same way that Kinsella must have been drawn into Graham’s life. But while Kinsella used Moonlight Graham as a subject for the examination of one’s greatest dreams and the importance — or lack thereof — of realizing them, Freeman’s 1880s card led me to consider the role that timing plays in one’s life.

It’s a nice card; as with all of the 1880s St. Louis Browns, the uniform is crisp and dazzling white, perfectly complemented by maroon trim and accessories. His features are sharp, and the pose . . . well, I can’t help but think that he’s practicing for a night of darts at the local pub rather than taking on the American Association’s top hitters.

So what meaning is there in a single game out of a major league season? Not much, really. Like Graham, who played a couple of innings as a defensive substitute and just missed a chance to bat, Freeman’s lone appearance was for a pennant-winning team, in a meaningless game after the championship had been clinched. Very few single games in a long schedule can really be called significant, but each one has it’s own identity, and taken by itself can give a snapshot of a team, a league, the players and the era.

And for Julie Freeman, that one game started out like a dream come true, and ended quite painfully.

————————————————–

Julius Benjamin Freeman was born Nov. 7, 1868 in . . . well, we don’t really know where, exactly, but it was somewhere in Missouri. Not much is known about the righthander until he turned up in Fort Smith, AR, as an 18-year-old who pitched well in the summer of 1887.

Although considered to be a hard thrower, Freeman’s most notable attribute was apparently his size, or rather his lack of size. Considering that pitchers of the day were not the 6-foot-plus specimens that they are in the 21st Century, Julie must have really been small in stature to have gained that notoriety in the 19th Century. The Sporting News referred to him as “a little bit of a lad” in one article. Even so, he appeared headed to the Kansas City Blues of the American Association for the 1888 season; an article in Sporting Life that spring referred to him as a “phenomenon, about whom a great deal was said.” So someone was paying attention.

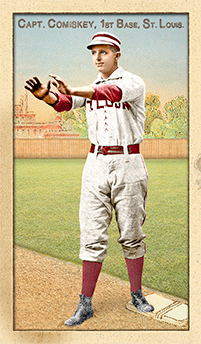

Kansas City ended up passing on his services, so Freeman returned home and spent the summer pitching for an independent team in Newton, MO. Charles Comiskey, St. Louis’ player-manager, must have been keeping tabs, because he eventually invited Freeman to work out with the Browns, and with the American Association pennant wrapped up, Comiskey offered the youngster a chance to start a league game, on Oct. 10, 1888.

The Browns had little for which to play that cold afternoon in St. Louis. They’d wrapped up their fourth consecutive American Association title a week or more earlier; since they ended up playing five games fewer than the runner-up Brooklyn Bridegrooms, it’s possible that the actual moment of clinching may not have been easily calculated or noted. But with a healthy lead in the standings all through the fall, the title was inevitable and the season rolled toward an eventual postseason meeting with National League champion New York Giants.

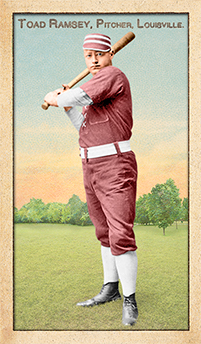

The opponent was the Louisville Colonels, who’d had a much different season. A few days later, they’d complete a 48-87 record, good for seventh place. The Colonels pitcher that day was Tom “Toad” Ramsey, and had the game been played in 1886 or 1887, when Ramsey won a combined 75 games, that might have sparked some fear in the heart of the St. Louis batters. But the Toad of 1888 was a different animal. Perhaps the heavy drinking for which he was known had taken its toll, or perhaps it was an indifference born of pitching for a team buried deep in the second division, but Ramsey was on his way to an 8-30 record.

The opponent was the Louisville Colonels, who’d had a much different season. A few days later, they’d complete a 48-87 record, good for seventh place. The Colonels pitcher that day was Tom “Toad” Ramsey, and had the game been played in 1886 or 1887, when Ramsey won a combined 75 games, that might have sparked some fear in the heart of the St. Louis batters. But the Toad of 1888 was a different animal. Perhaps the heavy drinking for which he was known had taken its toll, or perhaps it was an indifference born of pitching for a team buried deep in the second division, but Ramsey was on his way to an 8-30 record.

What little interest there was in the game centered around Freeman. The Cincinnati Enquirer reported that “Comiskey put in a young semi-professional pitcher named Freeman, who pitched last season for Fort Smith. He made a good record in Arkansas and was anxious to see what he could do against an Association team.” The Louisville Courier Journal referred to Julie as a”a young twirler from the Texas League,” and in the Chicago Tribune he was “a young Southern League pitcher.” The fact that Fort Smith competed in the Southwestern League is just proof that it was a lot tougher to get such facts straight in the days before media guides and web sites.

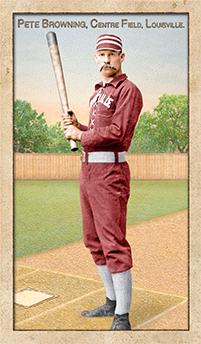

For three innings, Julie Freeman must have thought that the American Association was going to be a snap. He led the Colonels, 2-0, pitching against a lineup that, while it included Pete Browning and the wonderfully named William Van Winkle “Chicken” Wolf, admittedly included more than its share of second-stringers.

After that, things fell apart. Few of the Browns were accomplishing much at bat. Arlie Latham was the one exception, with two hits, but he also made two errors at third base. Meanwhile Louisville, batting in the bottom of the inning as was the prerogative for the visiting team for much of the 19th Century, scored five runs in the next three innings, taking the lead for good at 5-4 in the bottom of the sixth. Freeman did a good job handling Louisville’s top hitters, but light-hitting shortstop Phil Tomney had three hits.

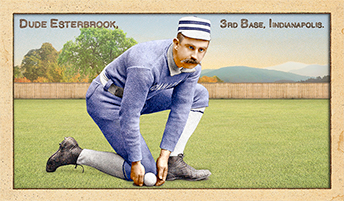

The end came suddenly for Freeman in the seventh. After retiring Browning, he faced Dude Esterbrook, the mercurial infielder who had been summarily released from Indianapolis a few months earlier but had given the Colonels a bit of a spark since his arrival in Louisville. He hit a hard line drive that caught Freeman on the right hand, breaking a finger. Julie was finished for the day, replaced on the mound by rightfielder Tommy McCarthy, the future Hall of Famer. Ramsey and the Colonels finished the day with a 7-4 victory.

The correspondent for the Cincinnati Enquirer judged of Freeman that “His work showed him to be a promising youngster and with the proper support he would have won yesterday’s game.” Comiskey must have concurred, because he reserved Freeman for the 1889 season and gave him ample opportunity to make the club. Freeman pitched the Browns’ exhibition opener, defeating the Missouri Athletic Club, 14-3, after which he continued to get work during the spring, mostly against amateur teams.

And this is where timing comes into play. Freeman’s date with the photographers shooting for the Old Judge card set no doubt came in the spring, after he’d already pitched what would  prove to be his lone

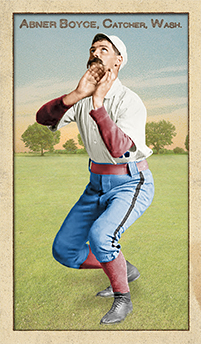

prove to be his lone  major league game. He’s featured in a handful of different poses. Consider the case of two other 1880s subjects, Walter Bogart and Abner Boyce. Neither ever played a major league game, but each was in the running for a spot on a major league roster in the spring, and appeared on Old Judge cards in the season that followed. Spring training was likely a good chance to get the various teams into a photo studio, and you can imagine the conversation: Him? Oh, that’s Walter. He might play some for us this year at first base, so we brought him along.

major league game. He’s featured in a handful of different poses. Consider the case of two other 1880s subjects, Walter Bogart and Abner Boyce. Neither ever played a major league game, but each was in the running for a spot on a major league roster in the spring, and appeared on Old Judge cards in the season that followed. Spring training was likely a good chance to get the various teams into a photo studio, and you can imagine the conversation: Him? Oh, that’s Walter. He might play some for us this year at first base, so we brought him along.

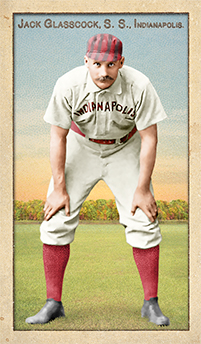

Bogart, whose fox-like features and rather disturbing sky blue, unitard-like Indianapolis uniform we see in the 1880s series, and Boyce, pictured in a Washington uniform and settling under a pop fly with all the apparent grace of a water buffalo, not only didn’t make it to the majors, but there is no record of either from the minor league database on baseball-reference.com. They almost certainly played professionally somewhere, but apparently not in a league whose records have been unearthed by the many researchers looking into such things.

But Julie Freeman played in the majors . . . and one and a quarter centuries later, he comes to life in the 1880s series, in that strange pose. That’s certainly some form of immortality. Once you’re a major leaguer, you’re a major leaguer for life. You’ve achieved what so many of us could only fantasize about, even if for only an hour or so one fall afternoon. It’s like being President, or Ambassador: you get to keep the title Former Major Leaguer the rest of your days.

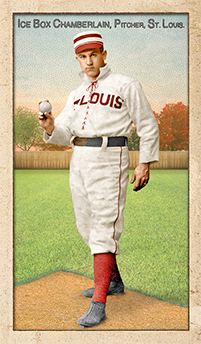

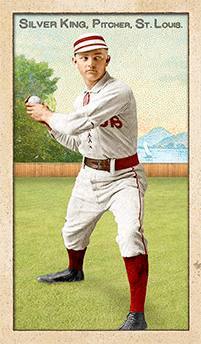

As you’ve no doubt figured, Julie Freeman didn’t make the St. Louis roster in 1889. Sure, he was 19 years old and had potential, but consider the rest of the pitching staff. Staff ace Silver King, who had a 45-20 record in 1888? Twenty years old. Nat Hudson, who was 25-10? Nineteen years old. On Sept. 1, the Browns had bought some pitching insurance with the purchase from Louisville of Elton “Ice Box” Chamberlain, who finished 11-2 for the Browns for a season record of 25-11. Chamberlain was 20. Heck, even Jim Devlin and Ed Knouff, who combined to start 20 games for the ’88 Browns, were 22 and 21, respectively. It was kind of difficult for Julie Freeman to stand out from that crowd.

After showing up well against amateur competition, Freeman was given a chance to pitch against the Detroit Wolverines of the National League, on April 8 in St. Louis. He lost, 7-3, walking seven batters, and 10 days later he was sold to the Milwaukee Creams of the Western Association. Comiskey was quoted as saying that Freeman wasn’t “heavy enough” to handle the rigors of an American Association season. Somewhere along the way, he developed arm trouble, and never won a game in Milwaukee. He got five starts, lost them all, and had a horrific WHIP of 2.333.

Freeman then moved to the Pacific Northwest, catching on with a team in Port Townsend, Wash., then finishing his pro career with a season at Helena in the Montana State League. And then he returned home and worked as a printer in St. Louis, playing for a semi-pro team sponsored by The Sporting News. He died in 1921, the victim of heart disease.

So Julie Freeman’s story may not be that riveting, certainly not compared to that of Moonlight Graham. The story of Graham ending up in the frozen wilds of Chisholm, MN, becoming a civic leader and its leading doctor, as portrayed in Field of Dreams? All true.

No, it’s not likely that anyone will be featuring Freeman’s life in a movie any time soon, with an actor the caliber of Burt Lancaster to play his part. But in one sense, he got the better of Graham. You see, Julie Freeman actually got to bat in a major league game, three times. And . . . he got one of the five hits that Toad Ramsey allowed that day.

And a .333 average is pretty good hitting in any league . . .

Sources:

baseball-reference.com

The Rank and File of 19th Century Major League Baseball by David Nemec

Oct. 11, 1888 editions of the Cincinnati Enquirer, the Louisville Courier Journal and the Chicago Tribune